The ancient Thracian gold treasure discovered in the village of Valchitran in modern-day Bulgaria in 1924 is one of the richest in the Balkans, emblematic of the region’s outstanding cultural elements.

Also known as the Valchitran gold treasure, it is exhibited in the Plovdiv history museum and it is the biggest such treasure found in the country, according to Bulgarian archaeologists.

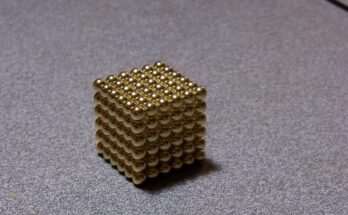

The precious archaeological find consists of 13 vessels, different in size and shape, weighing a total of 12.5 kg (27.5 lbs) and made of gold with a natural admixture of 9.7 percent silver.

They are estimated to belong to the 13th century BC and they are assumed to be a set of sacred ritual vessels, connected with the cult of Nature, the cult of the Sun more specifically.

The gold treasure

The biggest golden treasure known to the Bulgarian archaeology was found by chance while digging up a vineyard. It consists of 13 items, including:

- Seven lid-shaped objects of different diameters and an extended handle in the middle that makes them look like cymbals.

- Four deep one-handle cups with their handles bent upwards. One of the cups is much larger than the other three.

- A big bowl with high swung handles, weighing over 4 kg (9 lbs);

- A triple vessel, consisting of three almond-shaped pieces connected to each other with tubes, and with a handle with three branches forming a system of interconnected vessels.

Archaeologists assume the intended purpose of the artifacts: It is supposed that the Thracian king-priests used the vessels for religious rituals. More specifically the rituals were related to god Dionysus, worshipped by the ancient Greeks, as well as by the Thracians.

The triple vessel allows three different liquids to be poured in it, for example, wine, honey, and milk, or only two different liquids to be poured in the side (right and left) almond-shaped pieces, and when they mix thanks to the tubes a certain result becomes visible.

One theory is that the priest saw the result and would tell fortunes watching the middle piece of the triple vessel. We can only guess what the purpose of the cymbal-like items was. Were they really cymbals or were used as lids for other vessels? Is their shape related to the sun cult or is there another merely practical explanation?

The master goldsmiths made the small cups in such a way that they would stand in an upright position only when filled with liquid. Probably we will never find out the right answers to these questions but the Valchitran golden treasure gives us the opportunity to touch on antiquity in a unique and mysterious way. The treasure dates back to the end of the Bronze Age, i.e. to the 16th – 12th century BC.

The designs on the gold objects indicate that the craftsmen who made them were exceptionally skilled.

The Odrysian kingdom

The Odrysian kingdom, established around 470 BC by King Teres I, emerged as the most advanced among the Thracian states comprising various tribes united together. Thucydides suggests that Teres I seized this opportunity following the Persian setback in Europe after the unsuccessful invasion of Greece from 480–479 BC.

Teres and his son Sitalces succeeded in expanding their territories and made their kingdom one of the most powerful of its time, expanding from the Danube in the north to the outskirts of Abdera at the Aegean Sea. Throughout much of its early history, the Odrysian kingdom remained an ally of Athens and even joined the Peloponnesian War on its side.

Archaeological findings confirm that by the middle of the 5th century BC, a new and powerful elite had emerged that accumulated a wealth of precious artifacts of both local and regional origin. Burial practices changed after the Persian withdrawal and a new type of elite burial emerged in central Thrace as tombs with ashlar masonry have been found, sometimes with stone sarcophagi. The tomb of Rouets from the late 5th century even contained traces of wall paintings along with gold treasures.

By the turn of the 4th century, the Odrysian kingdom showed signs of fragmentation. Two rulers are known by 405 BC, as mentioned by historians: Amadocus I and Seuthes II. The historian Diodorus Siculus called them both “kings of the Thracians”, although this is most likely a misunderstanding.

The kingdom gradually declined and between 360 and 340 BC it disintegrated and was conquered by Philip II of Macedon