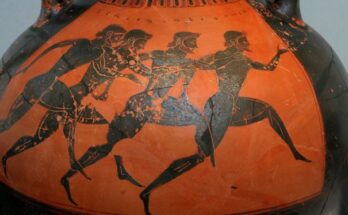

Ancient Greek athlete Coroebus of Elis was the first recorded Olympic Games winner in the 192-meter (630-feet) footrace in faraway 776 BC.

Coroebus was a cook, baker, and athlete from Elis. He won the stadion race, (or stade race), the only competition in the first recorded Olympic Games. The stadion race was a 180-meter (200-yard) sprint. The word stadion, the place in which the games took place, derives the Latin word stadium, which is also used in modern-day English. The original stadion track in Olympia measures approximately 190 meters (210 yards).

Coroebus’ prize at First-Ever Olympic Games

The prize Coroebus received was an olive branch. However, the honor of winning and becoming the very first Olympic champion in an event that was held to honor the god Zeus was far more prestigious than any prize could ever be.

Pausanias wrote about the first Olympics and Coroebus (Greek: Κόροιβος Ἠλεῖος):

“This I can prove; for when the unbroken tradition of the Olympiads began there was first the foot-race, and Coroebus an Elean was victor. There is no statue of Coroebus at Olympia, but his grave is on the borders of Elis. Afterwards, at the fourteenth Olympiad, the double foot-race was added: Hypenus of Pisa won the prize of wild olive in the double race, and at the next Olympiad Acanthus of Lacaedemon won in the long course.”

Panhellenic Games and the Olympic Games

Religious festivals in honor of Zeus were held long before the Olympic Games.

They took place in the sacred valley of Olympia and were believed to bring as much pleasure to the spirits of the dead as they did to the living. It is generally agreed by researchers that games in a similar context had begun an estimated 500 years before 776 BC.

Later, the festivals lost their local character and became Panhellenic. Four of them stood out. They attracted spectators from all over ancient Greece—the Olympian, Pythian, Nemean, and Isthmian. Of the four, the most important was the one in Olympia, dedicated to the Olympian Zeus. It was also the most widely attended event with visitors arriving from all over Greece even from abroad. Held every four years, it was also a measure of time, an Olympiad meaning four years.

Once every four years, wars between city-states or tribes were suspended, and trade activities stopped so that games could take place and people could attend in peace to honor the Olympian Zeus. It was called the Olympic Truce so that athletes could prepare and people could travel safely to Olympia. However, historians consider the Olympic Truce a modern-day romanticization. They argue that the only Olympiad concession was the safe travel of visitors to the games.

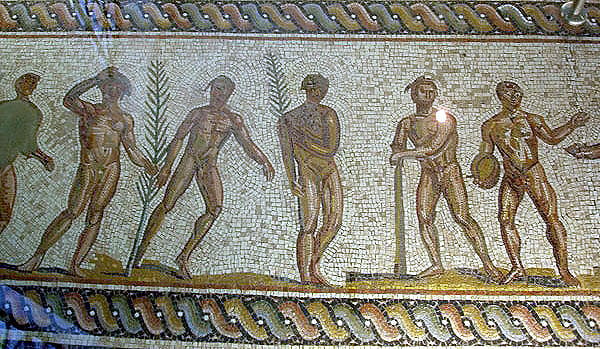

The stadium at Olympia was located to the east of the sanctuary of Zeus. It was where many of the sporting events of the ancient Olympic Games were held. The physical landmarks of the stadium are 212.54 meters (697.3 feet) long and 30 to 34 meters (98 to 112 feet) wide with four sloping sides around it—two at the sides and two at the ends. The sloping sides were grassy and could accommodate up to 40,000 spectators sitting on the grass.

Origin mythology

Myths were very important to ancient Greeks as a way to explain the origin of things. The site of Olympia and the games had to be rooted in some creation myth.

The oldest myth about how the Olympic Games began concerns Idaios Daktylos Heracles (not the famous Heracles, son of Zeus and Alcmene). The Daktylos (or Dactyls) were a mythical race of beings who came to being on Crete. They were associated with metalworking and were said to have taught mathematics and the alphabet to humans. According to the myth, the leader of these Dactyls, Heracles, founded the Olympic Games in the Age of Kronos.

Another myth involves King Oenomaus, who lived in fear of a prophecy that said that if his daughter, Hippodamia, would be married, his son-in-law would kill him. To prevent this from happening, he demanded that all of Hippodamia’s suitors challenge him to a chariot race. If they won, they could marry her, but if they lost, they would be killed.

King Oenomaus was certain he would win in every chariot contest because his horses were given to him by Ares, the God of War. However, when King Pelops—who the Peloponnese is named after—came to try his luck, Hippodamia fell in love with him at first sight and decided to help him win.

The two lovers conspired to sabotage the King’s chariot by loosening one of the bolts that attached the wheels. When the race began, it was close at first, but, eventually, the King’s wheel fell off, and he was killed in the accident. This meant that Pelops and Hippodamia could be married, fulfilling the prophecy. The games were then held every four years in honor of Pelops’ victory.