In 399 BC, Athens, the cradle of democracy and philosophy, tried and killed a seemingly innocent man in one of the most controversial trials in history. The defendant, Socrates, was a 70-year-old philosopher whose teachings profoundly influenced the city’s youth and intellectual landscape.

His execution by drinking poison hemlock remains a poignant episode in Western philosophy. Understanding why Athens killed Socrates reveals much about its sociopolitical and cultural dynamics.

The charges: impiety and corrupting the youth

Athenians charged Socrates with two primary offenses: impiety, or not believing in the gods recognized by the state, and corrupting the youth of Athens. Three citizens—Meletus, Anytus, and Lycon—brought these accusations. The charge of impiety stemmed from Socrates’ alleged introduction of new deities and his frequent questioning of traditional religious beliefs. His influential presence among the young men of Athens, encouraging them to question authority and think critically, led to the charge of corrupting the youth.

Socrates’ method, known as the Socratic method, involved asking probing questions to stimulate critical thinking and illuminate ideas. While now celebrated as a foundational method in Western education, it was perceived as subversive and dangerous in ancient Athens. His philosophical inquiries often left established norms and authorities exposed and embarrassed, earning him both admiration and animosity.

The sociopolitical context

To understand why Athens killed Socrates, it is crucial to consider the sociopolitical climate of the time. The city-state was recovering from the Peloponnesian War, which ended in 404 BC with Athens’ defeat by Sparta. The war had left Athens politically unstable, economically weakened, and socially fragmented. In this atmosphere of uncertainty, Athenians strongly desired to restore traditional values and order.

Socrates’ association with several controversial figures did not help his case. Among his followers were Critias and Alcibiades, both of whom had dubious reputations. Critias was one of the Thirty Tyrants, a pro-Spartan oligarchy that briefly ruled Athens and was known for its brutal regime. Alcibiades, on the other hand, was a charismatic and ambitious politician who had betrayed Athens by defecting to Sparta during the war. Although Socrates himself was not politically active, his connections to these men cast a shadow over his perceived intentions and loyalties.

The trial that led to his death

The works of his students, Plato and Xenophon, primarily document Socrates’s trial. In Plato’s “Apology,” Socrates presents his defense with characteristic wit and logic. He argues that he is a benefactor to the city, likening himself to a gadfly that stimulates a sluggish horse (Athens) to keep it vigilant and aware. He claims that his actions stem from a divine mission to seek and spread wisdom.

Despite his compelling defense, the jury, comprising 501 Athenian citizens, found him guilty. The verdict was close, with a narrow margin of about 30 votes. Socrates was given the opportunity to propose an alternative punishment to the death penalty. True to his principles, he suggested free meals for life, a reward usually reserved for Olympic champions. This perceived arrogance only alienated him further from the jury, leading them to impose the death penalty with a wider margin.

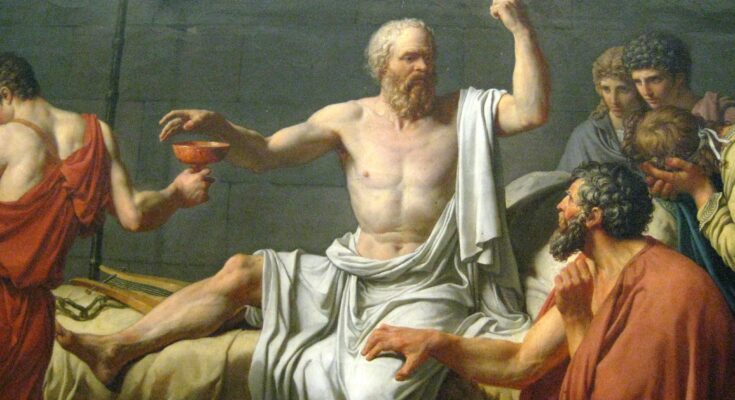

The execution

Athenians carried out Socrates’ death sentence by compelling him to drink a mixture containing poison hemlock. According to Plato’s “Phaedo,” Socrates faced his death with calmness and composure, engaging in philosophical discourse until his final moments. His dignified acceptance of the penalty solidified his legacy as a martyr for free thought and intellectual integrity.

Legacy and reflection of Socrates’ death

The legacy of Socrates’ trial remains significant even to this day. A recent recreation of his famous trial highlights its enduring impact and relevance in contemporary discourse. In a mock trial conducted by the National Hellenic Museum (NHM), Socrates was found not guilty. Such events underscore the timeless nature of the philosophical and ethical questions Socrates raised.

Such questions are a seminal event in the history of philosophy, symbolizing the clash between individual freedom and state authority. It highlights the dangers inherent in challenging societal norms and the potential consequences of fostering independent thought in times of political and social turmoil.

Why was Socrates killed?

Socrates’ death also raises enduring questions about the nature of justice and the philosopher’s role in society. Was his execution a necessary measure to preserve democracy, something Socrates opposed? Or was it a miscarriage of justice driven by fear and misunderstanding? Would we have democracy today if Athens had not executed him, instead allowing him to spread his anti-democratic sentiments?

One thing is sure: Socrates’ trial and death are a stark reminder of the perils faced by those who challenge the status quo. His legacy endures, inspiring countless generations to pursue truth, question authority, and value the unexamined life. The trial of Socrates is not merely a historical event but a profound lesson in the enduring struggle between freedom of thought and societal conformity.