A widely used antidepressant may offer new hope for curing glioblastoma, a rare and aggressive form of brain cancer. Researchers have discovered that this drug can significantly slow glioblastoma growth in human brain tissue and mice.

Dr. Michael Weller from the University Hospital Zurich highlighted its safety and affordability, suggesting it could soon be integrated into standard cancer treatment protocols.

Challenges of treating brain cancer

Glioblastoma is notoriously difficult to treat, with a survival rate of about 5 percent within five years of diagnosis. The main treatments include radiation, chemotherapy, and occasionally surgery.

The complexity of the disease and the blood-brain barrier, which blocks most drugs from entering the brain, further complicate treatment options.

Innovative research approaches

A team at ETH Zurich, led by molecular biologist Sohyon Lee, tested 132 drugs on glioblastoma tissues from patients. They recorded over 2,500 reactions to the drugs. They found that certain antidepressants, especially vortioxetine, were effective at inhibiting cancer cell growth.

Vortioxetine initiates a cascade of cellular reactions that prevent cancer cells from dividing. Researchers used computer models to understand how these reactions happen in brain and cancer cells. They found out that not all antidepressants can stop cancer growth because they don’t all trigger these reactions in the same way.

Promising preclinical results in using the antidepressant to cure brain cancer

To see if their findings would work outside of a lab, the team moved on to testing in mice. They implanted glioblastoma tumors into the mice and divided them into groups for various treatments. One group did not receive any treatment. Another group received an antidepressant called citalopram. The third group got vortioxetine.

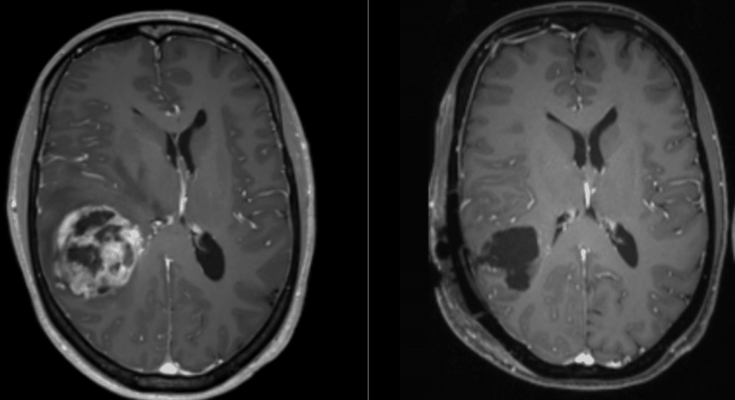

Exactly 38 days after tumor implantation, the group of mice that got vortioxetine showed much less tumor growth and spread compared to the untreated group and those given the antidepressant citalopram, which had similar results to each other.

In trials involving mice, those treated with vortioxetine had significantly less tumor growth compared to those untreated or treated with another antidepressant, citalopram. Another trial compared vortioxetine with standard chemotherapy, revealing that vortioxetine-treated mice had survival rates of 20 to 30 percent higher than those receiving only chemotherapy.

Clinical trials and cautions for the antidepressant in curing glioblastoma, a lethal form of brain cancer

The promising results from these studies point to the need for clinical trials to test the antidepressant to cure brain cancer in human patients.

Dr. Weller cautioned against self-medication, emphasizing the risks without proper medical supervision. “We don’t yet know whether the drug works in humans and what dose is required to combat the tumor, which is why clinical trials are necessary.” He further added, “Self-medicating would be an incalculable risk.”

Berend Snijder, also from ETH Zurich, remains optimistic about moving forward to patient trials, underscoring the potential of existing drugs to fight this lethal form of cancer. He said, “We started with this terrible tumor and found existing drugs that fight against it.”

Berend Snijder further added, “We show how and why they work, and soon we’ll be able to test them on patients.”