Climate change has reached the medical field. Europe has launched a new training program that aims to prepare young doctors to respond to health problems exacerbated by climate change. A network of experts will teach doctors-in-training about climate-related diseases.

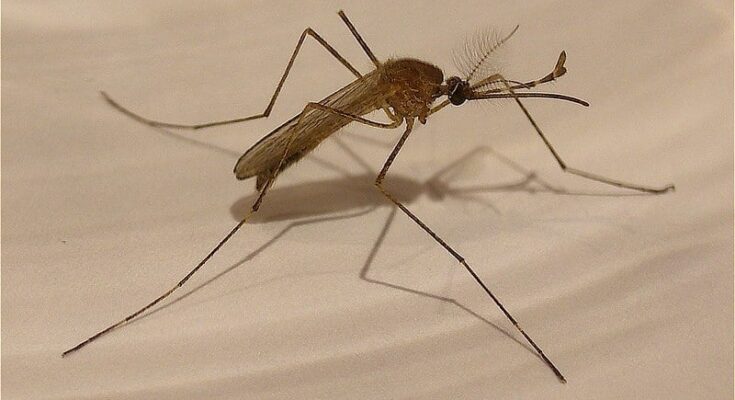

According to The Guardian, mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue and malaria will become a bigger part of the curriculum at medical schools across Europe due to the climate crisis.

Future doctors will also have more training in heat stroke recognition and treatment and will be expected to consider the climate impact of treatments such as asthma inhalers.

The impact of climate change on disease

Glasgow University’s Dr. Camille Huser, co-chair of ENCHE (European Network of Climate and Health Education) said: “The role of climate in teaching at medical schools varies widely and often consists of a single module or lecture.” The network predicts that in the future it will be “infused” into all teaching.

“Climate change…is not necessarily creating a whole new set of diseases that we haven’t seen before, but it’s exacerbating the ones that exist,” Huser said.

“Diabetes, for example, is not something that people associate with climate change at all, but the symptoms and complications are becoming more common and worse for people living in a world where the climate has changed.”

New treatments

Students are also being taught to support various activities such as walking or cycling instead of driving and “green prescribing,” whereby doctors encourage patients to take part in activities such as community gardening and tree planting. Both offer health benefits to individuals and are favorable for the environment.

Encouraging people to take care of their health has “huge benefits for them personally,” Huser said but also “will reduce emissions if they require less input from the health care system.”

He added that many people don’t realize that the health care sector is responsible for as many or more greenhouse gas emissions than the airline industry. “When you fly somewhere, you feel very guilty, but when you go to the doctor, you don’t feel guilty.”

Students will see how changes in the way an event is managed might have an impact. For example, the inhalers used to treat asthma emit greenhouse gases, so keeping the condition under control not only benefits the patient but also reduces the use of inhalers.

Some patients may be able to switch to dry powder inhalers, which emit fewer greenhouse gases if the devices are deemed suitable for them.

Although there have been piecemeal initiatives at the institutional level, network leaders say this is the first collaborative effort to focus on teaching medical students.

The network will also seek to influence national curriculum-setting bodies, such as the General Medical Council in the UK, to make the climate crisis a mandatory part of all physician training programs.

What is the goal of the network?

Huser’s co-chair, Professor Iain McInnes, also of the University of Glasgow, said the network’s aim is to “embed the debate into medical curricula so that future doctors are literate in this debate and don’t feel that this is an election issue.”

“This is as central and critical to their thinking as dealing with obesity, smoking and other environmental challenges,” McInnes said. “It’s just part of the DNA of being a physician.”

Climate change to affect health of all

ENCHE will serve as a regional hub for the Global Consortium for Climate and Health Education (GCCHE) at Columbia University’s School of Public Health in New York.

Professor Cecilia Sorensen, the director of GCCHE, said: “ENCHE is one of the most important training institutions in the country: Climate change will affect us all, everywhere, but not equally and not in the same way.”

“Regional networks are essential to help health professionals anticipate and respond to climate and health challenges that are unique to the communities where they practice,” Sorensen concluded.