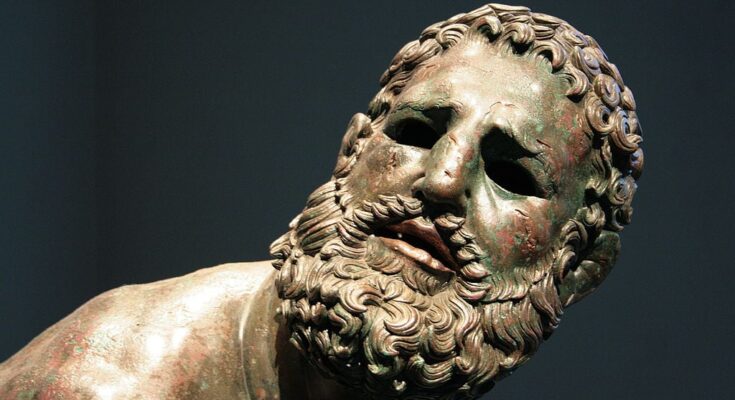

The beloved ancient Greek sculpture called “The Boxer at Rest” from 330-50 BC is one of the most realistic of all ancient Greek sculptures and also the most touching and emotive works of art from that period, reminding us that the pain and difficulties of human life are universal and beyond the bounds of time.

Created in an era when Hellenistic sculptors had gone beyond stylized, formal shapes and begun to portray humans with complete realism, the masterpiece is so lifelike that its viewers almost expect to see the man begin to move and speak.

It is difficult to believe how an ancient work of art could so encapsulate the realistic portrayal of ordinary people that only became the norm in modern times.

Unearthed in the gardens of Rome’s Quirinale Palace in 1885, it had been carefully buried centuries earlier — perhaps by people who did not want their beloved Boxer to become a victim of those who in Christian times were known to melt down pagan bronze sculptures.

The ancient Greek boxer is full of human emotion

In nearly perfect condition after almost twenty centuries, the sculpture is a flawless portrayal of the pain and suffering of ancient Greek boxers, while portraying the great dignity of a man who has fought for decades and yet still seems to be looking toward the viewer asking, “Must I fight again? Haven’t I done enough?”

The boxer is shown wearing the leather hand wrappings, or caestus, that pugilists from those times always wore in fights. These would serve as the only protection for boxers, who, like all other athletes, would compete in the nude.

It is possible that the Boxer had once graced the grounds of the Baths of Constantine. After the Goths invaded Rome, they destroyed the aqueducts that had led to the great city, leaving the Baths dry and leading to the decay of the entire area.

Like the statue of St. Peter at the Vatican, the fingers and toes of the Boxer had been worn down from many years of rubbing by those who visited the statue — leading experts to believe that the Boxer came to have magical or talismanic powers. This may have been why the sculpture had been buried so very carefully in later times.

As viewers have noticed over the centuries, the athlete’s broken, flattened nose, cauliflower ears and mien of complete exhaustion evoke a feeling of weariness, and perhaps even desperation, at the end of the man’s career.

Perhaps the artist wanted to portray the apprehension of an athlete at the end of his glory days, facing what he thinks maybe oblivion after decades of fame and adulation, looking with dread into an uncertain future.

One of the finest archaeological finds in centuries

The Boxer’s mouth and facial scars were actually inlaid with copper by the original artist, and other pieces of copper were inlaid on his shoulder, arm and thigh were meant to represent drops of blood, leading to an even more complete realism than we view today in the form.

Italian archaeologist Rodolfo Lanciani, officiated at the unearthing of the magnificent sculpture, later recorded his impressions of the monumental discovery at the Quirinale Palace.

“I have witnessed, in my long career in the active field of archaeology, many discoveries; I have experienced surprise after surprise; I have sometimes and most unexpectedly met with real masterpieces; but I have never felt such an extraordinary impression as the one created by the sight of this magnificent specimen of a semi-barbaric athlete, coming slowly out of the ground, as if awakening from a long repose after his gallant fights.”

Originally cast in eight pieces through the lost-wax process, later painstakingly soldered together, the bronze masterpiece was carefully conserved by art conservationist Nikolaus Himmelmann in 1989 before it went on display in Bonn, Germany.