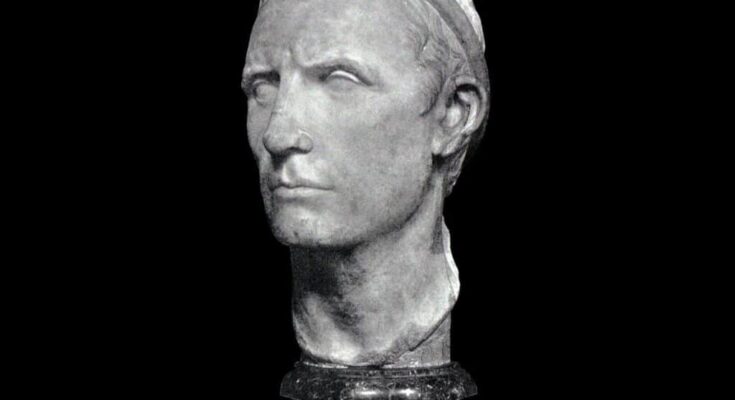

Antiochus III the Great was one of the most prominent Greek rulers and warlords of the Hellenistic (Greek) era.

He was a Greek Seleucid king and the sixth ruler of the Seleucid Empire. The Hellenistic period is perhaps the most intriguing and dynamic in terms of significant and rapid developments, constant action, ongoing tension, military conflicts and decisive battles.

All of this occurred in the context of an unending, bloody struggle among the successors of Alexander the Great’s generals. These sought to reestablish, through the consolidation of the Hellenistic kingdoms, the world empire of Alexander the Great. It was during this period that the heroic figure of Antiochus III rose. A man who endeavored to restore the glory of the Macedonian Empire.

Early Life and Ascension to the Throne

Antiochus III was born in 241 BC. As the son of Callinicos (Seleucus II) and Laodice, he became emperor of the Seleucid dynasty in 223 BC. He was crowned after the unexpected assassination of his brother, Seleucus III Ceraunus.

His highest ambition was the restoration of the Seleucid kingdom to the grandeur of Alexander’s empire.

Antiochus’ inexhaustible energy, unshakable will and unparalleled achievements rivaled those of Alexander the Great. He sought to consolidate complete control and suppress any threats to his absolute authority.

When Antiochus III ascended to the throne, he inherited a disorganized realm. Not only had Asia Minor (Anatolia) seceded, but the eastern provinces had also rebelled. Bactria under the Greek Diodotus and Parthia under the nomadic leader Arsaces. Shortly after Antiochus took power, the governors of Media and Persia, two brothers named Molon and Alexander, also rebelled.

The revolts in Media and Persia

Under the harmful influence of his minister Hermias, the young king approved an attack on Judea rather than personally addressing the revolts in Media and Persia. This attack ended in failure, and the generals sent against Molon and Alexander suffered a crushing defeat.

Following his initial failure to suppress the rebellions in Media and Persia, Antiochus began reorganizing the army. He was preparing for a determined campaign under his direct command.

Initially, Antiochus III needed to secure his control over the geostrategic region of Coele-Syria, threatened by the Ptolemaic Kingdom. At the same time he was covering his rear to prepare for the recapture of the eastern provinces.

The Fourth Syrian war and the “Anabasis” campaign

The conflict (221 BC – 217 BC), known as the Fourth Syrian War, was an attempt by Antiochus III to restore the size and glory of the Seleucid Empire, aiming to reach the level of expansion achieved by Seleucus I Nicator. Although Antiochus scored several impressive victories, the decisive event of the war was the Battle of Raphia (217 BC), a naval showdown.

In this battle, Ptolemy IV Philopator, ruler of the Hellenistic kingdom of the Lagids (Ptolemies), led an army of 50,000 men and defeated Antiochus III.

Antiochus’ subsequent campaign in Asia, known as the “Anabasis of Antiochus III”, highlights his remarkable abilities as a general, often compared to those of Alexander the Great. His campaign through Anatolia eventually earned him the epithet “the Great.” The Greek historian Polybius provides detailed accounts of this campaign and the great wars Antiochus waged.

In 216 BC, Antiochus campaigned north to confront Achaeus, and by 214 BC, he managed to trap him in Sardis. Antiochus besieged Sardis and eventually captured Achaeus. The city held out under the leadership of Achaeus’ widow, Laodice, until 213 BC, when it finally surrendered. After securing central Asia Minor, Antiochus extended his authority to the borders of the Kingdom of Pergamum.

The Greek king of Syria gathered an army of 45,000 men, consisting of 10,000 Greek mercenaries, 8,000 silvershields (Argyraspides), 2,500 Cretan archers, 2,000 companions (hetairoi), 1,000 elite cavalry from the Agema, along with other Greek and Asian contingents. With this army, Antiochus aimed to reclaim the eastern satrapies for the Seleucid Empire.

The Armenian campaign

Around 213/212 BC, Antiochus set out from his capital, Antioch in Syria, marching towards Armenia. After moving through Mesopotamia and Urfa, the Seleucid army advanced on the Armenian capital, Armosata (in southern Armenia). Antiochus laid siege to the city, located between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The Armenian satrap, Xerxes, fled upon seeing the size of the Greek army. Fearing occupation, he sent ambassadors to negotiate peace with Antiochus.

Although Antiochus’ advisers urged him to capture Armosata, depose Xerxes, and install his nephew Mithridates on the throne, the king chose a different course. Instead of following their advice, Antiochus summoned Xerxes and ended hostilities, showing leniency. He forgave much of Xerxes’ debt to the Seleucid Empire, requiring him to pay only 300 talents, along with 1,000 horses and 1,000 mules. Additionally, Xerxes agreed to marry Antiochus’ sister, Antiochis.

Campaign against the Parthians

In the winter of 210-209 BC, Antiochus III crossed Ecbatana (modern-day Hamadan) during his campaign against the Parthians. During this campaign, he confiscated gold and silver from the Iranian temple of Anahita (whom the Greeks identified with Artemis), an act of sacrilege for which the pro-Roman historian Diodorus Siculus later harshly criticized him. Despite this controversy, Antiochus managed to gather 4,000 talents to fund his campaign.

As Polybius informs us:

“Arsaces had expected Antiochus to advance as far as this region, but he did not think he would venture with such a large force to cross the adjacent desert, chiefly owing to the scarcity of water. For in the region I speak of there is no water visible on the surface, but even in the desert there are a number of underground channels communicating with wells unknown to those not acquainted with the country.

Arsaces, however, when he saw that Antiochus was attempting to march across the desert, endeavored instantly to fill up and destroy the wells. When the king heard the news, he sent Nicomedes with a thousand horsemen. Discovering that Arsaces had withdrawn his army but left some cavalry to destroy the channel mouths, Nicomedes attacked and routed them, forcing their retreat, and then returned to Antiochus.

The king, having traversed the desert, came to the city called Hecatompylus, which lies in the center of Parthia. This city derives its name from the fact that it is the meeting place of all the roads leading to the surrounding districts.”

Defeat of the Parthians and the battle of Mount Labus

The Parthian monarch, Arsaces II, was forced to negotiate after suffering defeats on the battlefield, particularly in the Battle of Mount Labus and the Siege of Syrinx. Polybius informs us that Mount Labus led to Hyrcania. The Macedonian phalanx pressed the Parthians, who fought vigorously, but during the night, the Euzones, in a flanking maneuver, captured the enemy’s positions and forced them to flee.

By blowing trumpets, Antiochus halted their hasty retreat and encamped in the unwalled city of Tambrax, in Hyrcania. Polybius adds:

“He (Antiochus) advanced with his army and, encamping around it, began the siege. His main tactic involved the use of mantelets for the sappers. There were three moats, each not less than thirty cubits wide and fifteen deep, each defended at the edge by a double row of palisades, and behind all, there was a strong wall.

Due to his superior numbers and personal vigor, Antiochus quickly filled the moats, undermined the wall, and caused it to collapse. The barbarians, thoroughly discouraged, massacred all the Greeks in the town and looted the finest goods before fleeing in the night. When the king learned this, he ordered Hyperbas and his mercenaries to pursue the barbarians. Once overtaken, the barbarians abandoned their encumbrances and retreated to the town. When the peltasts pressed through the breach, they surrendered in despair.”

The Parthians seek refuge in Syrinx and massacre Greeks

The Parthians found refuge in the nearest Greek fortress city of Syrinx, a Greek settlement founded by Seleucus Nicator. The Seleucid army camped outside the city, initiating the siege. They assigned the brunt of the labor to the loggerhead turtles. Syrinx was heavily fortified, with triple trenches measuring thirty cubits wide and fifteen deep. It was reinforced by additional double trenches and a formidable wall. Additional double trenches and a formidable wall reinforced it. As Antiochus’ workers filled the trenches, fierce hand-to-hand combat erupted both above ground and in the tunnels they dug below. Eventually, Antiochus’ presence invigorated his workers, and they succeeded in demolishing the wall and breaching the city’s defenses.

The Parthians massacred the Greek population of Syrinx and fled during the night. Antiochus pursued them with his mercenaries, and in battle, the Parthians abandoned their baggage and fled back to Syrinx in fear. However, the Syrian peltasts entered the city through a breach made by Antiochus’ siege engines and forced the enemies to surrender.

After this, Arsaces was compelled to conclude a treaty with Antiochus. He agreed to leave open the trade route that connected the western and eastern parts of the Seleucid Empire. Garrisons were stationed in key cities, which would pay tribute taxes.

Bactrian campaign and battle of Arius

After his victory in the Parthian campaign, Antiochus III advanced to Bactria, where Euthydemus I, a Greek from Magnesia, ruled as king.

Antiochus, bypassing southern Margiana, invaded Arius (modern-day Herat in Afghanistan). Messengers informed Antiochus that Euthydemus was waiting for him on the banks of the Arius River with a force consisting of 3,000 Greeks, 7,000 Bactrian and Persian cavalry, and an additional 5,000 Greek archers. The Greco-Bactrian army had taken positions along the river crossings to block the Seleucid army from advancing.

According to Polybius, the Greco-Bactrian army occupied strategic river crossings, hoping to prevent Antiochus’ forces from gaining access. The Seleucid army was divided into two divisions. Antiochus, leading 2,000 Companion cavalry, 8,000 Euzones, and 10,000 Peltasts, marched ahead of the other division to secure control over the river’s resources.

When the Bactrian cavalry received reports from their scouts about the Seleucid advance, they moved swiftly to engage Antiochus’ division while it was still on the march. Recognizing the need to withstand the initial charge, Antiochus called upon 1,000 of his elite cavalry, accustomed to fighting in close proximity to him, and ordered the rest of his cavalry to form up in squadrons and take their regular positions. Leading his force, Antiochus personally engaged the Bactrians in battle.

Antiochus fought bravely, and during the encounter, his horse was killed beneath him, and he himself received a wound to the mouth, losing several of his teeth. Despite both sides suffering significant losses, Antiochus’ army ultimately prevailed. Euthydemus retreated with his forces to the city of Bactra Zariaspa (modern Balkh).

Diplomatic negotiations and peace agreement

Polybius recounts that during negotiations between Antiochus and Euthydemus, the latter defended his position to Teleas, Antiochus’ ambassador. Euthydemus argued that Antiochus was unjustified in attempting to depose him, as he had not revolted against the Seleucid king.

Instead, he claimed that after others had rebelled, he had seized control of Bactria by eliminating the rebel leaders. Euthydemus also presented himself as a defender of Hellenism against the barbaric Scythian hordes, implying that his reign had preserved Greek culture in the region.

Polybius further mentions that Teleas mediated several times between the two Greek kings until Euthydemus finally sent his son, Demetrius, to formalize a peace agreement. Antiochus warmly received Demetrius, who eventually married him to one of his daughters.

They agreed that Euthydemus would retain his throne but as a vassal of the Seleucid kingdom. He provided Antiochus with 30 war elephants, provisions, and a contingent of light Greek infantry. Antiochus later used these elephants in future battles, including the Battle of Magnesia against the Romans.

Antiochus III: the third Greek conqueror of India

After his victory in Bactria, the Greek king Antiochus III continued his campaign into India. Passing through the Indian Caucasus, he conquered several Indian tribes near Alexandria Eschate until he encountered the powerful king Sophagasenus.

Polybius mentions that the Indian ruler realized he could not withstand the superior Greek forces. Therefore, he invited Antiochus to renew their old friendship and accepted Greek sovereignty over Pentapotamia.

It was agreed that Sophagasenus would provide Antiochus with additional war elephants. This would bring his total number of elephants to 150, as well as provisions and large sums of money. For the collection of these resources, Antiochus sent Androsthenes of Cyzicus.

Antiochus III was the only king after Alexander the Great and Seleucus I to successfully establish Greek sovereignty in India.

The fifth Syrian war: The capture of Coele Syria and the conquest of Egypt

According to Appian, in the winter of 203/2 BC, Antiochus III and Philip V decided to conclude a secret treaty. This aimed at dividing the territories of the Ptolemaic state between them. According to this treaty, Antiochus could claim Cyprus, the Ptolemaic possessions in Cilicia and Lycia, as well as southern Syria. Philip would claim the Cyclades Islands, which belonged to the Ptolemies, along with the coasts of Thrace and Asia Minor.

Antiochus conquered Damascus in 202 BC. This helped him prevent any Ptolemaic counterattack from the Bekaa position. It facilitated his connection to the northernmost part of this valley and his military base at Apamea.

At the beginning of the Fifth Syrian War (202-198 BC), Antiochus III the Great occupied Coele Syria. In 199-198 BC, Attalus, the king of Pergamon, invaded Greece, and in his absence, the Seleucid king invaded his lands. Subsequently, Scopas the Aetolian, a general of Ptolemy V, invaded Coele Syria with a force of 6,000 infantry and 500 cavalry, recapturing it on behalf of Egypt.

According to Polybius, Antiochus III first took Gaza by siege. He then led his army to Paneion against the Egyptian forces. General Scopas positioned the Ptolemaic phalanx with a few horsemen on the right flank, at the foot of Mount Hermon, and the remainder of the cavalry on the left in the plain.

Antiochus stationed his phalanx at the northernmost point of the battlefield, accompanied by heavily armed cavalry. He commanded the army with his son, Antiochus the Younger, serving as the commander of the battalions.

In front of the phalanx he positioned war elephants at intervals, along with Antipater’s Tarantine horsemen. He filled the gaps between the elephants with archers and slingers.

The conquest of Egypt and the decisive battle

The king himself commanded the cavalry of partners and auxiliaries positioned behind the elephants.

He stationed a smaller section of the Seleucid phalanx south of the river that divided the battlefield and the cavalry also accompanied it. In contrast, the Ptolemaic forces lined up their phalanx, flanked by Ptolemaic cavalry.

The Seleucid cavalry attacked, dislodging the Egyptian cavalry, and then turned towards the opposing phalanx, which engaged the Seleucid forces. The battle involved intense fighting between the phalanxes, war elephants, horsemen, and heavily armed euzones. The historian Zeno notes that when the Aetolian horses faced the wall of elephants, they were frightened and could not penetrate, a claim Polybius questions.

In the northern part of the battlefield, the Seleucid army’s attack was successful, leading to the irretrievable defeat of the Egyptian phalanx. In the southern part, however, the Aetolians emerged victorious.

Realizing that the only thing he could save was the army he had brought from his homeland, the Aetolian general left the Ptolemaic phalanx to be destroyed. Antiochus, having let the Aetolians go, concentrated on crushing the Ptolemaic phalanx. Its total defeat would weaken the Ptolemaic government significantly. This was undoubtedly a decisive battle. The destruction of the Egyptian army left the Ptolemaic government powerless to reclaim Coele Syria. It was eventually conquered by the Seleucids.

King Antiochus attributed his victory to the intervention of this deity and, in gratitude, officially established the cult of Pan in the cave and the surrounding sanctuary.

In 195 BC, Ptolemy reached a peace agreement with Antiochus, allowing the Seleucid king to retain control of Coele Syria. As part of the treaty, Ptolemy agreed to marry Antiochus’ daughter, Cleopatra I. After many wars, Antiochus III the Great would be the first king to achieve total Seleucid victory over Ptolemaic Egypt.

The legacy of the heroic Antiochus III the Great

The glory of Antiochus III the Great and his achievements were unmatched for his time. He not only proved to be the most worthy heir to the legacy of Seleucus I Nicator, but also a warlord. A general whose military skills and successes we can only compared to those of Alexander the Great. Antiochus restored the glory of the Seleucid kingdom but also expanded it nearly as far as Alexander himself had reached.

However, his successes would not last forever. During the Roman-Syrian War (192-188 BC), he was ultimately defeated by the Romans and the Kingdom of Pergamon. The humiliating Treaty of Apamea resulted in Antiochus losing the vast majority of the lands he had conquered. The outlying provinces of the empire, which had been recovered by Antiochus, reasserted their independence.

Yet, even after such humiliation, Antiochus III sought to reclaim these provinces. In 187 BC, he led an eastern expedition in Luristan but was killed while pillaging a temple of Bel in Elymaïs, Persia. This marked a true glorious warrior’s death.