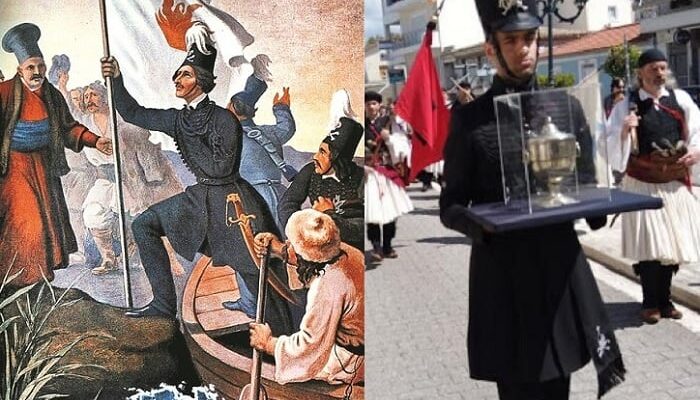

Alexandros Ypsilantis, a member of the Filiki Eteria group that coordinated the beginning of the Greek War of Independence, died a hero on January 31, 1828.

Almost 200 years later, his heart rests in peace in a small church, a few meters from Syntagma Square, in the very center of Athens.

Along with the heart of his brother Dimitrios, the war hero’s heart is kept in a silver urn as a reminder of the eminent history of one of the pioneers of the Greek Revolution of 1821.

It was the last wish of Ypsilantis, who formed the Sacred Band (Ιερός Λόχος), comprising young Greek volunteers from all over Europe, for his heart to be embalmed and sent to Greece.

His wish was realized by one of his brothers, George Ypsilantis, who brought it back to the homeland, where it still rests today.

Ypsilantis’ contribution to the Greek War of Independence

Well before March 25, 1821 and the breaking out of the Greek War of Independence, Ypsilantis had already decided that the first blow against the Ottoman Empire should be made outside Greece.

A founding member of the Filiki Eteria, Ypsilantis had made a general plan for the uprising, which was revised in May of 1820 in Bucharest, with the participation of other Greek rebels.

The plan was to aid the revolt of Serbs and Montenegrins, provoke a revolt in Wallachia,

provoke civil unrest in Constantinople, and burn the Ottoman fleet at the city’s port.

After that, Ypsilantis would go to Greece and start the revolution in the Peloponnese.

Having fought wars in the Russian Army, where he had already been promoted to Major General by Tsar Alexander, Ypsilantis was well-qualified to hold a position of power in the war of the Greeks.

He issued a declaration on October 8, 1820, announcing that he would soon be starting a revolt against the Ottoman Empire.

Ypsilantis chooses Wallachia to start revolution

Information on the Filiki Eteria and its activities had unfortunately been leaked to the Ottoman authorities, making Ypsilantis hasten the outbreak of the revolt in Wallachia and participate personally.

Legally, the Ottomans could not move their forces into Wallachia or Moldavia without Russian permission, so if the Ottomans sent troops there, Russia might go to war.

The governor of Moldavia, Michael Soutsos, was a Phanariot Greek who was secretly a member of the Filiki Eteria.

However, he was also an opportunist and a turncoat — who secretly informed the government of the Ottoman Empire of the planned invasion.

On February 22, 1821, accompanied by several other Greek officers in Russian service, Ypsilantis crossed the Prut River at Sculeni and entered into the two Principalities.

Two days later, at Iasi, Ypsilantis issued a proclamation, announcing that he had “the support of a great power,” meaning Russia.

Ypsilantis was betting on Orthodox Russia to intervene should the Ottomans invade Wallachia or Moldavia to quell the rebellion.

However, Tsar Alexander was still a committed member of the Holy Alliance, and acted swiftly to disassociate himself from Ypsilantis.

Ypsilantis was denounced for having misused the Tsar’s trust, and was then stripped of his rank and commanded to lay down his arms.

Ottomans assemble troops to enter Wallachia

Ypsilantis’ public fall from grace with the Tsar emboldened the Turks, who began assembling a large number of troops to quell the insurrection in Wallachia.

Ypsilantis was also short on money and could not even pay his troops, so they turned to plunder for their remuneration. He was then forced to march to Bucharest to enlist volunteers.

In Bucharest, Ypsilantis found that he could not rely on the Wallachians to continue their revolt for assistance in the Greek cause.

Ypsilantis and other Greek leaders believed that the Wallachians and Moldavians would support the Greek cause, on the base of their common Orthodox faith.

However, he had underestimated the increasing resentment of Greek domination in the Principalities and the first stirrings of what would become Romanian nationalism.

It was then that the Sacred Band was formed, comprising young Greek volunteers from all over Europe.

Ottomans defeat Ypsilantis and the Greek Army

The Ottomans crossed the Danube River with 30,000 troops, ready to suppress the revolt and defeat Ypsilantis’ outnumbered army.

And, tragically, this is where the Greek general made a tactical mistake: Instead of advancing on Braila to prevent the Turks from entering the Principalities, he retreated to Iasi.

There, after a series of long battles, the Filiki Eteria Army was defeated, with the final blow dealt at Dragatsani on June 19.

Ypsilantis never went to Greece after that point, as he had planned for so long. He finally retired to Vienna — where he died, destitute, on January 29, 1828.

The once-proud Major General’s last wish was to have his heart removed and sent to Greece — and that wish was fulfilled.

His heart is kept in the chapel of the Pammegistoi Taxiarches, at 6 Stisihorou Street, located behind Greece’s Presidential Mansion.