For the first time, scientists have tracked the journey of stem cells years after a transplant, uncovering details about a medical process that has puzzled doctors for over 50 years. This groundbreaking study offers insights that could improve donor selection and increase successful transplants’ chances, potentially leading to safer and more effective outcomes.

New discoveries on stem cell survival

In a study by researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and the University of Zurich, scientists observed how stem cells behave in patients’ bodies up to 30 years after a transplant.

Published in Nature and partially funded by Cancer Research UK, the study found that transplants from younger donors—those in their 20s and 30s—tend to have more surviving stem cells, with about 30,000 long-term cells.

In comparison, transplants from older donors left only 1,000 to 3,000 stem cells, which may explain why transplants from younger donors are generally more successful.

The team noted that fewer surviving stem cells from older donors could lead to weaker immune systems and a higher chance of relapse for the patient. These findings confirm that donor age plays a critical role in the success of stem cell transplants.

Transplant effects on the blood system

Stem cell transplants are often the only curative treatment for blood cancers like leukemia and lymphoma, which affect over a million people worldwide each year.

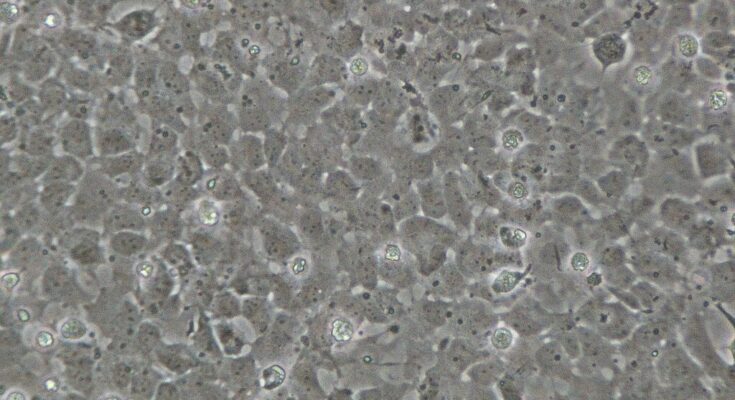

The procedure involves replacing a patient’s damaged blood cells with healthy stem cells from a donor, which then work to rebuild the patient’s blood and immune systems. Each year, more than 2,000 people in the UK undergo this life-saving treatment.

While transplants have been performed for decades, many questions about their long-term effects remained unanswered. This study has shown that the transplant process effectively ages a patient’s blood system by 10 to 15 years, primarily due to a reduction in stem cell diversity.

Genetic stability and new treatment possibilities

The research also revealed that stem cells gain very few new genetic mutations while rebuilding the patient’s blood. The low mutation rate suggests that stem cells remain stable under intense conditions, offering hope for improved transplant outcomes.

Dr. Michael Spencer Chapman, lead author of the study, explained, “When you receive a transplant, it’s like giving your blood system a fresh start, but what actually happens to those stem cells? Until now, we could only introduce the cells and then just monitor the blood counts for signs of recovery. But in this study we’ve traced decades of changes in one single sample, revealing how some cell populations fall away while others dominate, shaping a patient’s blood over time. It is exciting to understand this process in such detail.”

Beyond donor age, the study identified other genetic traits that enable certain stem cells to thrive. This discovery may lead to new treatments that enhance stem cell survival, making transplants safer and more successful for a wider range of patients.