An ancient warrior whose previously broken jaw was mended with gold thread was recently unearthed in Greece; recent scholarship has revealed that he had been operated on using a technique propounded by the Greek physician Hippocrates 1,800 years earlier.

Killed on the battlefield in a desperate fight against the Ottomans in the fourteenth century, his jaw had been shattered by a blow at least ten years earlier.

The warrior, who may have been the leader in charge of the fort where his head was found, was decapitated by the Ottomans either during the fight or as a type of humiliation afterward.

In those times, it was common to place heads of deceased enemies on spikes to demoralize their people.

A recent analysis of the skull, which was first unearthed in 1991, shows that his broken jaw was repaired with gold wires wrapped around his molars to keep it in place.

And the method worked, according to Anagnostis Agelarakis, a professor of anthropology at New York’s Adelphi University, who, along with his colleagues, first uncovered the fighter’s skull and lower jaw at Polystylon Fort, an archaeological site in Western Thrace, Greece.

Agelarakis explains not only that “the jaw was shattered into two pieces,” but that it was skillfully healed by noninvasive means that had been propounded by none other than the Father of Medicine, Hippocrates, in the fifth century BC—1,800 year before the fighter’s jaw was smashed in battle.

The professor, speaking in an interview with Greek Reporter recently still openly marvels at how “the medical professional was able to put the two major fragments of the jaw together,” calling him “an erudite, educated individual.”

Ancient warrior healed with 1,800-year-old Hippocratic techniques

The battlefield doctor working in the Byzantine Empire 650 years ago must have had knowledge of the treatise written in the time of Ancient Greece.

“In one of the dentitions, I saw that the tooth was filed a little bit so that the knot that was tied in the wire would not scratch the cheek,” Agelarakis explains. “It’s very sophisticated —it’s flabbergasting.”

With the death blow that killed the man being one of extreme force, Agelarakis notes in his new study that the fort of Polystylon “did not surrender…it must have been taken by force.” The skull showed that there had been a “horrendous frontal impact” that occurred at or just before the time of death.

After the fort fell to the enemy and its defender was beheaded, someone most likely took his head and buried it; this was most likely done surreptitiously, probably without the “permission of the subjugators, given that the rest of the body was not recovered,” Agelarakis explains.

The action that must have been taken out of love and respect for the warrior took on an even more poignant aspect after the researchers found that the tool used to dig into the grave was just a broken piece of pottery found at the site.

Perhaps there wasn’t time and it wasn’t safe to be seen digging a proper grave, so whoever did this final service for the fallen man placed his head in a grave already belonging to a five-year-old child. It is not known if he and the child were related.

Located in the center of a cemetery with twenty plots at Polystylon fort, the burial site had been undisturbed through the years until found by Agelarakis and his team.

Because the man’s lower jaw and the rest of his skull were found together, it appears that his head most likely had soft tissues, including muscle and skin still on it when it was buried after the battle in the mid-1380s, according to the professor.

Showing visible signs of healing after the first injury, Agelarakis immediately noted the unique find and published his discovery in a scientific paper published in the journal Byzantina Symmeikta in 2017.

It took time, however, to piece together just how the healing had occurred, looking at the evidence of dental accretions that had accumulated around what must have been the tiny wires holding the man’s jaw together.

Gold wires wrapped around molars anchored warrior’s jaw

In addition, Agelarakis undertook thorough research into the milieu of the time, including the surgical techniques used in Byzantine Greece. He states that the “closed intervention,” meaning the technique of addressing the fracture without opening up the area surgically, that was practiced on the warrior, would by its very nature have to have involved wrapping wires around the man’s molars as “anchors. That’s the only way you can do it,” he explains to Greek Reporter.

And, of course, the evidence of these wires, which would have to have been made of mostly gold, is still there, in the form of the calcareous deposits around them. As Agelarakis says, there must have also been some silver mixed in with the gold as an alloy, to make it strong enough to withstand the forces involved.

Of course, after such a long time in the ground, there is no wire left at all, but Agelarakis believes it was gold, with just enough of a silver alloy to make it strong. Any more silver content would have left the telltale marks of gray on the teeth,

Likewise, there also was no other metallic patina or signs of cupric acid, which in the case of copper or bronze, would have left the greenish hue behind as they decomposed.

Warrior’s jaw wiring received skilled adjustments

“It must have been some kind of gold thread, a gold wire or something like that, as is recommended in the Hippocratic corpus that was compiled in the fifth century B.C.,” Agelarakis says.

What may be even more surprising, he adds, is that the man’s jaw repair underwent a series of adjustments over time. Due to the constant movements involved in eating, talking, and going about the other activities of life, he says, there must have been many different adjustments made by the skilled medical practitioner.

This also shows, he says, the high status of the warrior, who must have been an extremely prominent individual in that area.

All these insights are part of the professor’s new paper on the remarkable find, published online in the September issue of the journal Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry.

Agelarakis says that he cannot be sure what caused the original fracture, but since the man clearly was a warrior, it was likely something involved in combat, either from a projectile propelled by black powder, falling from a horse, or a spear head.

According to the professor, the warrior was killed when he was between the ages of thirty-five and forty years old.

If the warrior was still fighting after his injury ten years before his death, that would entail a retinue of people who made special foods for him to eat since his jaw was wired until it healed, Agelarakis says.

There is no way to know if the warrior’s tongue was also wounded in the incident, but it would be impossible to believe that there would not have been speech problems for the unfortunate man after his horrific injury, especially since, as Agelarakis says, there must have been muscular damage, as well.

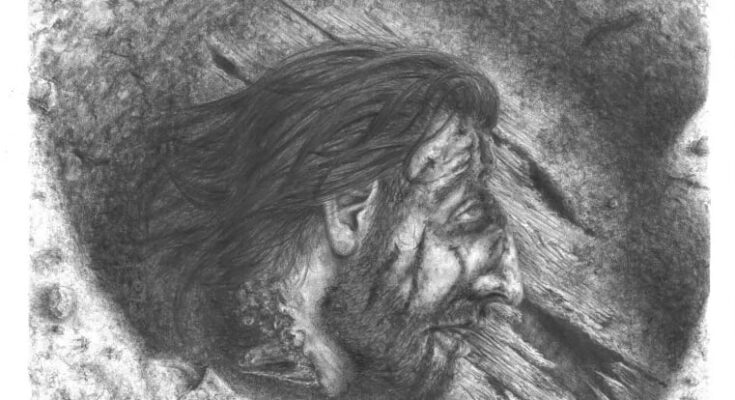

The professor noted that if the warrior had a beard, he could certainly have hidden any disfigurements that resulted from his horrific injury.

The medieval town of Polystylon was part of the ancient city of Avdera. The fortification of Polystylon was built around the 7th or 8th century AD. The Byzantine-era walls were based on the walls of the ancient acropolis of Avdera.

The Byzantine historian Nikiforos Grigoras believes that in 1342 Ioannis Kantakouzenos reinforced the fortifications of Polystylon, repairing the upper part of the fortification, the so-called “Byzantine acropolis.”

Before the 13th century, Polystylon was the seat of a bishop, or Metropolitan, but over the course of the following centuries, the Latin conquest and other turmoil caused its decline. The area was abandoned around 1380, the time of the great battle that took the life of the warrior.