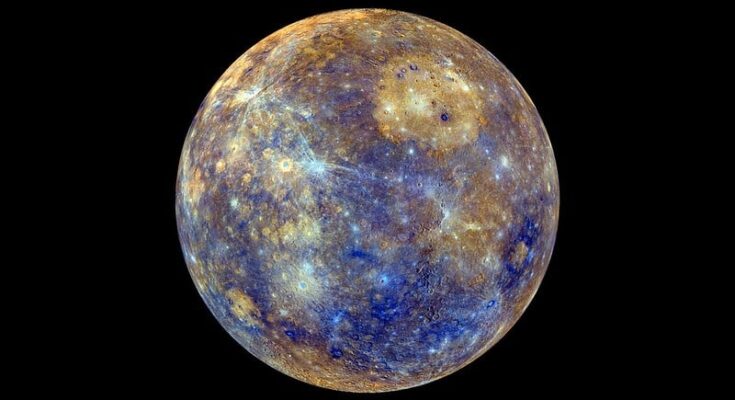

A new study suggests Mercury might have a thick layer of diamonds deep under its surface. This discovery could help scientists understand more about the planet’s makeup and unusual magnetic field.

Mercury holds many mysteries, including a surprisingly weak magnetic field and dark surface patches made of graphite, a type of carbon, identified by NASA’s Messenger mission. This discovery caught the attention of Yanhao Lin, a scientist at the Center for High-Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research in Beijing.

Formation of diamonds beneath Mercury’s surface

Scientists believe Mercury formed like other rocky planets despite its peculiarities. The process likely began with a hot magma ocean. This ocean on Mercury was probably rich in carbon and silicate. As it cooled, metals gathered to form a central core. The rest of the magma then crystallized to create Mercury’s middle mantle and outer crust.

For a long time, researchers believed that the temperature and pressure in Mercury’s mantle were only high enough for carbon to turn into graphite. Since graphite is lighter than the mantle, it would float to the surface.

However, a study in 2019 proposed that Mercury’s mantle might be 80 miles deeper than previously thought. This greater depth would significantly increase the pressure and temperature at the boundary between the core and mantle. These conditions could allow carbon to crystallize into diamonds.

New simulated experiments

To study this idea, scientists from Belgium and China, including Yanhao Lin, made chemical mixtures with iron, silica, and carbon, similar to what they thought Mercury’s early magma was like. They also added iron sulfide because Mercury’s surface has a lot of sulfur.

They used a special machine to put these mixtures under very high pressure at about 70,000 times greater than the pressure on Earth. They also heated the mixtures to very high temperatures, similar to conditions deep within Mercury.

The scientists then used computer models to see what happens at Mercury’s core-mantle boundary. These models helped them understand how graphite or diamond could form under those conditions. According to Lin, these models provide important insights into the planet’s interior.

Results of simulated experiments

The new experiments showed that minerals like olivine probably formed in Mercury’s mantle, which aligns with earlier research. Adding sulfur made the mixture solidify at higher temperatures, which is better for forming diamonds.

This week’s figure shows the formation of a proposed interior structure of Mercury, including the creation of a diamond layer. This layer formed due to the solidification of Mercury’s inner core where diamond crystallized and floated upwards to the core-mantle boundary. (1/2) pic.twitter.com/hdCdktkgoW

— Planetary Plot of the Week (@PlanetaryPlots) June 30, 2024

Computer simulations suggested diamonds could have formed when Mercury’s inner core solidified. These diamonds, being lighter than the core, would then rise to the core-mantle boundary. The calculations indicated that if diamonds are present, they could form a layer about 9 miles (15 km) thick.

Impracticality of extraction

Mining these diamonds is not possible. The extreme temperatures on Mercury and the depth of the diamonds, about 300 miles (485 km) below the surface, make extraction impractical. However, these diamonds might play a key role in Mercury’s magnetic field.

The study’s results could also shed light on the evolution of carbon-rich exoplanets. Lin mentioned that the processes forming a diamond layer on Mercury might occur on other planets, potentially exhibiting similar signs.