In the early days of the modern Olympics, the Games weren’t just about sports – they also featured art competitions.

Before they exclusively set their focus on athletic events, they included categories for various art forms, where for example one could win a medal for a poem or a painting. For the Ancient Greeks too, art was seen as an Olympic sport. Besides “classic” sports like running or wrestling, the Olympics in Ancient Greece featured competitions for art, music, and even sculpture.

The inclusion of art competitions in the modern Olympics was the idea of French Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the Olympic Movement. Inspired by the values of the Ancient Greeks, who believed in cultivating both mind and body equally, Coubertin wanted to bring art and sport together.

Art competitions in the modern Olympics covered five areas: architecture, literature, music, painting, and sculpture. To stay true to the spirit of the Games, all entries must be inspired by a sport, from track and field to swimming and even football.

When art first became an Olympic sport

In modern history, the first time art counted as an Olympic sport was at the 1912 Summer Games in Stockholm, Sweden. Initially, artist participation wasn’t very big, but it grew over the next few Olympics, reaching its peak in 1928 in Amsterdam with over 1,100 works submitted.

Notable works from the early Olympic art competitions include Jean Jacoby’s paintings “Etude de Sport” and “Rugby,” which captured scenes of football and won gold medals in the mixed painting and drawing categories in 1924 and 1928, respectively. Another notable piece is Walter W. Winans’ bronze sculpture “An American Trotter,” which earned a gold medal in 1912.

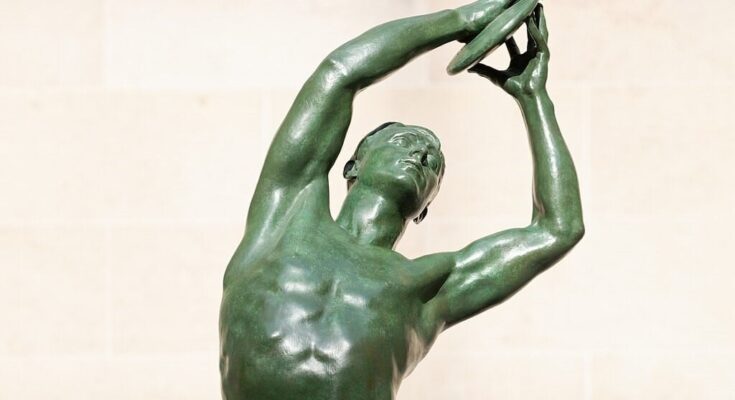

Greece has won one medal in the art competitions, in the category of mixed sculpturing. Exactly a century ago, in the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, Konstantinos Dimitriadis won gold medal for his sculpture “Discobole Finlandais” (“Finnish Discus Thrower“). This was a 7-foot-tall sculpture of a nude athlete preparing to throw the discus.

However, by 1948, interest in art competitions in the Olympics had waned. Controversy over whether professional artists had an advantage in the Games led to the replacement of art competitions with exhibitions in 1954. Since then, art has not been part of the Olympic program.

And while the reasons for removing art from the Olympics are understandable – like professional artists having an unfair advantage and the subjective nature of art compared to the clear-cut results of sports – one might wonder about the role of sculpting.

Can sculpting be considered a sport?

Sculpting stands out from other art forms like painting or literature because it’s three-dimensional. Sculptors work with materials like stone, sand, or ice, engaging with their art in a physical way that painters and poets don’t. In fact, this physicality closely resembles sports, and sport itself is considered an art form by many.

Both sculpting and sports demand years of dedication and physical effort. Making a sculpture involves long hours of work that has to be precise, maneuvering around the piece, and carefully handling tools – much like athletes perfect their technique. Just as high jump athletes must position their body perfectly to clear the bar, a sculptor must manage his tools and position his body well to shape the work.

Moreover, both sculpting and sports rely on mathematics. Sculptors and athletes use principles like geometry, calculus, and statistics to achieve the best possible result.

Sculpting as an Olympic event

Bringing sculpting back in the Olympics might seem like a far-fetched idea, but it could be promising for the future. Given the similarities between sculpting and sports, adding it to the Games could help revive an art that’s becoming less visible today. While paintings and novels are often in the spotlight, sculpture isn’t as widely recognized in mainstream media. As an Olympic event, its status would be elevated.

Just as art in the early modern Olympics had to be inspired by sports, sculpting would also follow this rule. Artists would compete with each other within a set timeframe to craft the best sculpture. Their sculptures would then be judged and scored on set criteria like difficulty and execution, much like how gymnastics routines are evaluated.

Moreover, sculpting in the Olympics would also contribute to our cultural legacy for future generations. This is clear in how artworks from past Olympic art competitions have endured over time. For example, Konstantinos Dimitriadis’ medal-winning sculpture was restored and rededicated outside Icahn Stadium on Randall’s Island in March 2024, a century after its creation.

Can we bring back sculpting in the Olympics?

At the Paris 2024 Olympics, breaking -a form of street dance- made its debut, allowing dancers to compete with each other. This move marked an important step towards including more diverse arts in the Games and hints at the possibility of a wider range in the future, maybe even including sculpting.

For now, sculptors in Paris have the opportunity to display their work during the Cultural Olympiad, a series of events running across France until September. These events aim to bridge art and sport, just as Baron de Coubertin would have wanted. This also suggests that the future may offer new opportunities for sculpting to once again become part of the Olympic movement.