The village of Neokaisaria, with its 300 inhabitants, is located between Mount Olympus and the Pieria Mountains in Greece and is home to a spectacular mastodon museum.

Opposite the church, this mastodon museum draws attention to itself with a picture of one of these proboscideans on its façade. Visitors are greeted here by Savas, chairman of the museum’s supporting association and the guide for the day.

Mastodons were mammals similar to mammoths but differed in height and length as well as the structure of their molars, which gave the species its name. The name comes from Greek: Mastos means ‘breast,’ and donti stands for ‘tooth.’ This may sound unusual, but it quickly becomes understandable when one sees such a tooth. It resembles the milk bars of a suckling bitch.

The males could reach a length of six meters and were therefore longer than today’s elephants. They also had gigantic tusks up to five meters long. The females were smaller but still imposing. Adult bulls weighed about 20 tons, whereas today’s elephants weigh six to seven tons. The species could live to be 60 to 80 years old, and their diet consisted of plants, of which they consumed 350 to 400 kilos (770 to 880 pounds) per day. Much like today’s elephants, they lived together in herds.

Before visitors get to the protagonist of this beautiful mastodon museum in northern Greece, Savas makes it a little more exciting.

Fossils and discoveries in Greece’s mastodon museum

To get a feel for the animals’ habitat, Savas uses diagrams to depict the geological structure of the time. The various geological eras are also well illustrated so that one can place the existence of the animals in time.

Some fossilized finds show what coexisted with the mastodons. On display are fossilized shells, and it is interesting to learn that the coast of the Mediterranean once stretched all the way here some 8.5 miles (14 km) from the current beach. Savas shows visitors the skeletons of smaller animals and very well-preserved fossilized leaves. They are intact, and, if one didn’t know their actual age, one could mistake them for pressed leaves from the previous fall.

Asked how the remains of the mastodon came to be found, he turned to another display board with photographs. “Here is a picture of the place where it was found,” he said. “In this hollow, 500 meters from here, farmers were digging fine sand to mix it with the soil in their fields. They came across the bones in the process. Back then, in May 2014, nobody had any idea what they had found there.”

Palaeontologists from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki carefully uncovered the bones. This was relatively simple, as the fine sand could easily be removed with brushes. Before the finds could be removed, they had to be stabilized. These bones and tusks had been lying buried in the ground for millions of years, protected from the sun and weather. If they were picked up untreated, they would have crumbled to dust.

That’s why they were coated with a resin-based chemical and had to rest for a day before they were removed. A makeshift laboratory was set up on-site for further treatment. There, scientists identified the bones as the remains of a mastodon. An important indicator of whether it is a mammoth, mastodon, or elephant is the structure of the tusks.

The structure of the tooth is decisive. If the ivory is straight, it belonged to a mammoth or elephant. If, on the other hand, it runs out towards the edges of the tooth, it was part of a mastodon.

At the site, which was already three meters deep, visitors could dig another four meters down to the end of the sand layer. There were hopes of finding some kind of “elephant graveyard,” but, unfortunately, visitors discovered nothing else. The bones they found belonged to an approximately 25-year-old animal that lived between six and nine million years ago. It was around four meters long (without tusks), measured 2.50 meters high, and weighed 6 tons. Apparently, it got stuck in the swamp and died.

In order to appropriately present the finds, an association was founded, which also oversees the mastodon museum. The museum was and is financed solely by donations without receipt of state aid.

The modern exhibition

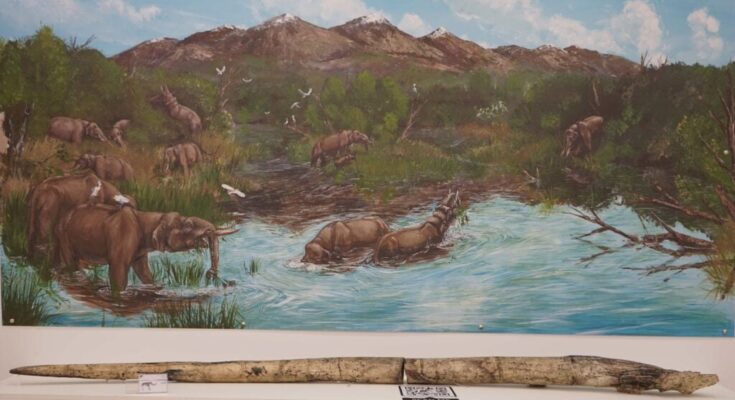

Visitors then turned to the modern, well-lit exhibition. Two wall-sized paintings caught their eye. One shows two pachyderms plucking grass, which are not depicted as life-size due to the lack of space. A colorful painting depicts a herd grazing in the water before the then much lower Olympus Mountains (then approximately 1150 meters, or 3,772 ft, and today 2918 meters, or 9,573 ft).

The paintings are by the Dutch artist Remie Bakker, who specialized in the lifelike depiction of prehistoric animals. He also created the two models of a male and a female mastodon. They are made on a scale of 1:10 and very detailed. A wooden figure illustrates the immense size difference between a human and an animal. In front of the landscape painting lies an approximately three-meter-long tusk of a male animal. It comes from another site—1,500 meters (4,921 ft) away from Greece’s mastodon museum.

Vulnerable artifacts are stored in glass cabinets. Some rib bones were reinforced with metal and plaster to preserve them. A massive shoulder bone and tusks are on display but unprotected. Small diagrams display where the exhibits were once placed on the body.

Savas explains the glittering inclusions in some of the bones as the result of an exchange of substances. Parts of the calcium were dissolved out of the bones and replaced by minerals from the surrounding soil. This process ultimately leads to bone fossilization.

Finally, Savas led the visitors into his small office. Their gaze fell on a wooden box filled with stones. “These are parts of a fossilized giant tortoise from Makrygialos,” says Savas. “Experts still have to reconstruct them and then we’ll look for a place to exhibit them.”

The tour concludes here, and Savvas patiently answers a few more questions. Visitors thank him for the information and wonder what other secrets the area around Mount Olympus in Greece has to offer.