The recent Olympics controversy surrounding the Feast of the Gods and the Last Supper has renewed interest in divine dinners. These celestial suppers symbolize divine intervention, covenant-making, and the intertwining of gods with the mortals.

Despite their vast differences in context and purpose, the events are also remarkably similar. They reflect how a simple meal can foreshadow monumental events, illuminating gripping insights into the ancient Greek and Christian worlds.

Significance of banquet events

The divine dinner on Mount Olympus is a scene to behold. The marriage of Thetis, a sea nymph, and Peleus, a mortal king, is a celestial affair bridging the divine and mortal realms. Attended by the crème de la crème of the Greek pantheon—Zeus, Hera, and Poseidon, among others—this event is not merely a social gathering but a significant turning point in Greek mythology. It leads to the birth of Achilles and ultimately influences the Trojan War. The gods, with their power and presence, make this event one of monumental importance.

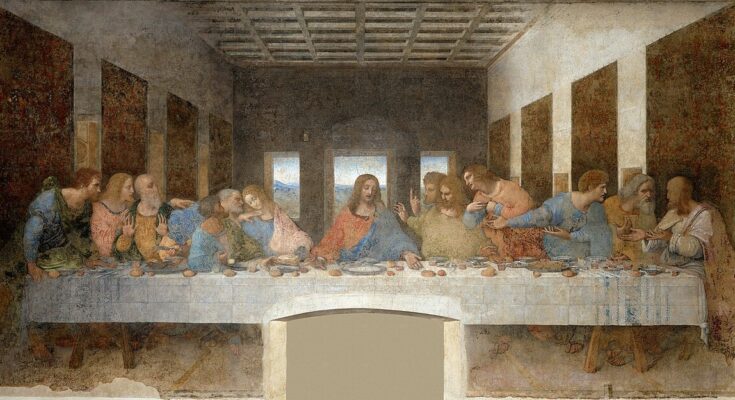

In contrast, the Last Supper is an intimate, somber gathering of Jesus and his twelve apostles. This meal marks Jesus’ final meal before his crucifixion and is central to Christian theology. It symbolizes the establishment of a New Covenant between God and humanity. The Last Supper sets the stage for the Passion of Christ, leading to his sacrifice and subsequent resurrection, foundational to Christian beliefs. This meal, heavy with meaning, highlights themes of sacrifice, redemption, and divine love.

Gathering of important figures in supper

Both events gather key figures in their respective traditions. The divine banquet includes Zeus, Hera, and Poseidon in addition to other deities. These each represent various aspects of the cosmos and human experience. Their presence underscores the event’s significance and the interconnectedness of divine affairs with mortal destinies. Each god and goddess, with their distinct domain and power, adds to the grandeur and importance of the occasion.

Similarly, the Last Supper involves Jesus and his apostles, pivotal figures in the Christian narrative. Jesus, the Son of God, shares this critical moment with his closest followers, who will become the leaders of the early Christian Church. The apostles’ presence highlights the transition from Jesus’ earthly ministry to the spread of his teachings following his resurrection. It is a moment of profound significance, marking the beginning of a new chapter in Christian history.

Symbolic acts and rituals of feast

Symbolism abounds in both events. The gods’ behavior and interactions at the divine banquet often reflect their domains and powers. Apollo might be depicted playing the lyre, symbolizing music and prophecy, while Dionysus may be shown with wine, representing festivity and ecstasy. These symbolic acts reinforce the gods’ identities and roles within the mythological framework, adding layers of meaning to the event.

At the Last Supper, Jesus’ actions are profoundly symbolic. He breaks bread and shares wine with his disciples, declaring them his body and blood. This act institutes the Eucharist, a central sacrament in Christianity. The symbolism of the bread and wine as Jesus’ body and blood signifies the new covenant and Jesus’ impending sacrifice for humanity’s redemption. These acts are laden with theological significance and have inspired centuries of Christian practice and reflection.

Impact on post-feast events

Both dinners foreshadow significant events. The divine dinner indirectly leads to the Trojan War. Eris, the goddess of discord, was not invited to the banquet and, in her anger, threw a golden apple inscribed “To the fairest,” which led to the judgment of Paris and the eventual war. Her vengeful ploy illustrates how a slighted deity’s actions can unleash chaos and conflict, underscoring the interconnectedness and often unintended consequences of divine and mortal actions.

Similarly, the Last Supper directly precedes Jesus’ arrest, trial, torture, crucifixion, and resurrection. Judas Iscariot, one of the apostles, betrays Jesus for thirty pieces of silver, driven by greed and the love of money. His actions set into motion a chain of events that lead to Jesus’ crucifixion. Like Eris, Judas is a disgruntled figure whose actions precipitate disaster, though, in his case, the motivation is not revenge but financial gain. This betrayal underscores human frailty and the devastating impact a single individual’s choices can have on a larger narrative.

Nature and tone in meal

The context and nature of these dinners differ significantly. The divine banquet is a mythological event set in the grandeur of Mount Olympus, celebrating a marriage and the union of divine and mortal realms. It reflects the ancient Greeks’ view of their gods as powerful yet capricious beings directly influencing human affairs.

The Last Supper, however, involves historical figures, notably Jesus of Nazareth. The event is the cornerstone of Christian theology, representing key themes of sacrifice, atonement, and the new covenant between God and humanity. It has inspired countless theological reflections, liturgical practices, and artistic representations, underscoring its centrality to Christian faith and worship.

Cultural and religious context

The cultural and religious contexts of these events are distinct. The divine dinner is part of Greek mythology, a rich tapestry of stories explaining natural phenomena, human behavior, and cultural practices. These myths were integral to the ancient Greeks’ understanding of the world and their place within it.

The Last Supper, however, is a linchpin of Christian theology. It embodies themes of sacrifice, atonement, and divine-human relationship. It has fueled countless theological debates, liturgical traditions, and artistic endeavors, reflecting its deep significance in Christian belief.

Divine dinners in ancient Greek and Christian traditions

Though separated by time, culture, and context, there are intriguing parallels between the divine dinner celebrating Thetis and Peleus and Jesus’ Last Supper. Significant figures are gathered for a meal, there are symbolic acts involved, and major events are foreshadowed. These divine dinners in ancient Greek and Christian traditions reflect the diverse ways in which the act of sitting down for food becomes more than merely a meal. It is a sacred act during which heaven and earth collide, and history can be written with every passing plate.