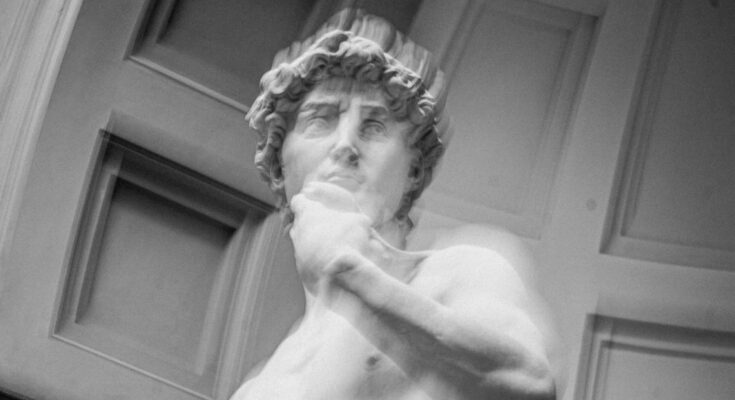

Michelangelo’s David is a towering figure in art history. Yet this masterpiece embodies an underlying tension between established tradition and newfound knowledge. David represents both a humble biblical shepherd boy who became a king, and a Greek hero. This duality reflects Michelangelo’s mastery of blending both cultural worlds.

David as a biblical hero

David is firmly rooted in the biblical narrative. As the boy who defeated Goliath, he embodies faith and divine justice. Michelangelo captures this with David’s intense gaze and his stance, poised to strike.

His David isn’t depicted in the act of victory but in the moments before. This choice emphasizes David’s faith in God. It also aligns with Renaissance ideals of moral virtue.

Michelangelo’s contemporaries, such as Giorgio Vasari, saw David as a Christian hero. Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists, praises the statue for its spiritual significance. Michelangelo’s depiction reflects David’s divine mission.

It’s not just physical strength but spiritual resolve that makes him a hero. This interpretation resonated with a Florence that viewed itself as a “new Jerusalem,” standing against its enemies.

Resistance to the Classical Revival

The Renaissance was a period of remarkable intellectual and cultural resurgence in Europe, characterized by the rediscovery of Classical texts and the study of ancient Greek and Roman ideals.

This revival was not just about art. It was a profound transformation of how people viewed the world and their place in it. However, this rediscovery resulted in significant tension between the Classical and Christian worlds.

Figures such as Girolamo Savonarola, a Dominican friar and puritanical reformer, vehemently opposed the Renaissance’s embrace of Classical antiquity. He believed that the revival of pagan philosophy and art was leading Christians away from the true teachings of the Church.

Savonarola’s influence was significant in Florence, and his calls for moral and religious purity culminated in the infamous “Bonfire of the Vanities,” where books, art, and other objects deemed immoral were destroyed.

Despite this tension, like many artists of his time, Michelangelo demonstrated that the Christian and Classical worlds needn’t be at odds. In his work, Michelangelo found a way to harmonize these seemingly opposing traditions.

David as a Greek hero

Michelangelo’s David is a prime example of this synthesis. By sculpting David in the nude and employing the idealized forms of Greek heroism, he was not abandoning Christian values. Instead, Michelangelo expressed Christian themes through a Greek lens.

David embodies both the biblical hero’s spiritual virtues and a Greek god’s physical perfection. This blending of ideals is what makes the statue so striking and enduring.

More specifically, the iconic statue also embodies the qualities of Greek heroism. His nudity, idealized form, and contrapposto stance are straight out of the Greek tradition.

These elements are not incidental but deliberate references to Greek sculpture, mainly works like Polykleitos’ Doryphoros. In this way, David transcends his biblical role, becoming a universal symbol of human potential.

In his book Michelangelo’s Nose: A Myth and Its Maker, Paul Barolsky suggests that Michelangelo saw himself in David. Barolsky argues that Michelangelo identified with the Greek heroes of antiquity, seeing in them a reflection of his own struggles and aspirations.

David, a product of Michelangelo’s ideas, embodies the Florentine aspiration, adding a layer of complexity to the Biblical hero. This turns the Biblical hero into a symbol of both divine favor and human achievement.

Consequently, the Florentine captures the essence of the Renaissance, a period where artists and thinkers sought to reconcile the wisdom of antiquity with the spiritual teachings of Christianity, creating a new cultural paradigm that would define the era.

The secret duality of Michelangelo’s David

As much as Michelangelo’s masterpiece can be seen as art, it is also a feat of engineering. In a period when tensions ensued between established tradition and newfound knowledge, the Florentine genius “solved for x.” Michelangelo’s experiment proved that Biblical virtue and Greek representation are not at odds.