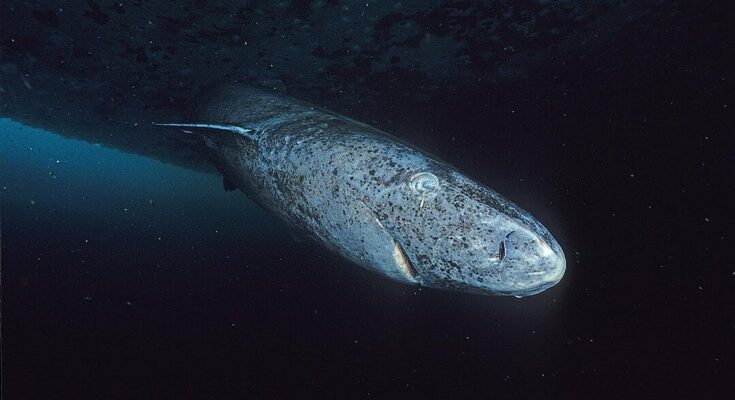

Researchers have made progress in uncovering the secrets behind the long life of the Greenland shark, the world’s longest-living vertebrate. These sharks can live up to 400 years or more. They live in the icy waters of the North Atlantic and Antarctic oceans.

To survive in such cold environments, Greenland sharks have especially slow metabolisms. They swim slowly—less than 1.8 miles per hour—and grow only about 0.4 inches each year. These unique adaptations might hold the key to understanding their longevity.

Ewan Camplisson, a Ph.D. student at the University of Manchester in the UK, explained to Newsweek that, in many species, including humans, we typically observe changes in the activity of metabolic enzymes with the progression of aging. Some enzymes may decrease in activity, while others might increase to maintain high energy production.

Five different enzymes studied in Greenland sharks

Enzymes play crucial roles in cells by facilitating chemical reactions. In their study of Greenland sharks, Camplisson and his team focused on five enzymes involved in muscle chemistry. Surprisingly, they found no age-related changes in these enzymes unlike what is typically seen in other animals.

Studies based on 28 Greenland sharks determined by radiocarbon dating of crystals within the lens of their eyes, that the oldest of the animals that they sampled had lived for 392±120 years and was consequently born between 1504 and 1744. pic.twitter.com/X7QZVlkwuX

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) April 30, 2024

“We don’t see any variations with increasing age in the five enzymes we tested in the Greenland sharks’ red muscle,” he said.

“This suggests that they aren’t showing this traditional sign of aging which we would expect to see in most animals. This gives us some insight into their longevity, and with further research we may be able to determine if their metabolism is a significant factor in their long life span,” he explained.

Sharks’ hearts function the same as humans

The heart is important for both humans and sharks, though they have significant anatomical differences. Human hearts have four chambers, whereas shark hearts only have two. Despite this structural variation, there are similarities in how their hearts function at the cellular level, according to Camplisson.

Camplisson explained that by uncovering the adaptations that enable Greenland sharks to live exceptionally long lives without significant cardiovascular issues, we could potentially apply similar strategies to improve human cardiac health.

This could particularly benefit the elderly population, which is most affected by cardiovascular conditions, potentially enhancing overall quality of life. Much remains unknown about how Greenland sharks defy aging, but Camplisson remains optimistic that studies like these are moving us forward.

“I believe that once we fully understand how the shark can live so long and what specific adaptations it has, we can try to incorporate these into treatments that will reduce the risk of some age-related conditions such as cardiovascular disease, which is seen most significantly in the elderly population,” said Camplisson.