Hercules is a symbol of strength and heroism with an enduring legacy. Beyond his well-known exploits in the Mediterranean, he played a critical role in linking the Greek world to the ancient Near East.

This cultural synthesis, particularly evident during the Hellenistic period, highlights Hercules as a figure that transcended his origins to become a shared icon across diverse civilizations, bridging the gap between East and West.

Cultural confluence in the Hellenistic Middle East

The Hellenistic period, following Alexander the Great’s conquests, saw extensive cultural exchange and integration. Alexander’s campaigns expanded Greek political dominion and facilitated the mingling of Greek and Eastern cultures. Babylon, a city of immense historical and cultural significance, became a focal point for such intercultural exchange.

Alexander admired Babylon greatly and envisioned it as the capital of his empire. Upon his arrival, he was given a warm reception. The Babylonians honored him as “King of the World.” This reception was both political and cultural. The Greek presence brought new ideas, traditions, and mythologies. Among these, the myth of Hercules emerged as a particularly potent symbol of this cultural fusion and served as a link between East and West.

Hercules in Mesopotamian context

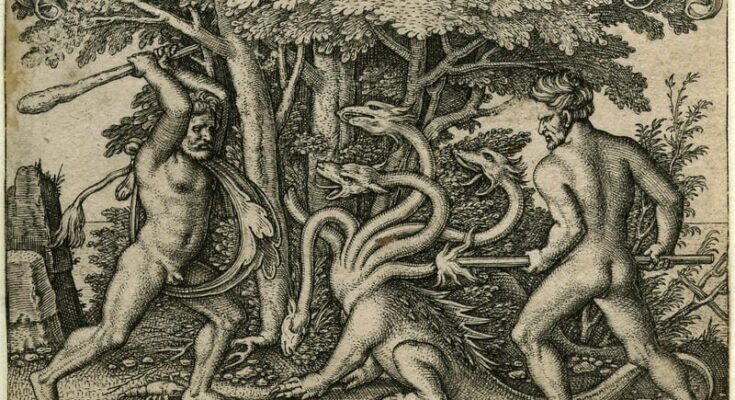

Hercules’ integration in the Near East is most evident in the terracotta figurines found in regions such as Seleucia-on-the-Tigris, modern-day Iraq. These figurines depict Hercules in familiar Greek forms—bearded, muscular, and adorned with the lion skin and club. However, these attributes also resonated deeply with local traditions. The figure of Hercules closely resembled local heroes depicted in Assyrian and Persian art, particularly the lion-hunting figures prominent in palace reliefs and seals.

In her 2013 study, Stephanie Langin-Hooper contends that the male nudity-club-beard combination appealed to Babylonians because of the pre-existing Assyrian and Persian lion-hunting motif. Hercules was popular because his characteristics could effortlessly be compared to those of an established figure.

This might explain why alternative depictions of Hercules, such as the Apples of the Hesperides (as depicted in the Farnese Hercules statue) and the downturned and exhausted Hercules, were much less common.

Hercules’ popularity becomes even more apparent when considering that Apollo was worshiped as the divine ancestor of the Seleucid kings, the rulers of Hellenistic Babylon. Oddly enough, a bronze statue from Seleucia bearing the inscription Hercules and Verethragna, a Parthian god, was dedicated at the temple of Apollo.

The Babylonians had such an affinity for Hercules that, even in a temple of another god, they would rather dedicate a figurine closer to their hearts. Hercules ceased to be a foreign god once viewed as the sum of all his parts. He was an archetypal figure that transcended peoples and cultures and was Eastern as much as he was Greek. Consequently, mythology could have familiarized and found common ground for two unacquainted ethnic groups through a recurring archetype.

Hercules on coins and in art

The use of Hercules’ image on coins further underscores his role as a cultural bridge. Coins from the period depict Hercules in various forms. These often highlight his heroic attributes that resonated across cultures. For instance, coins from the reign of Hyspaosines, a local ruler, feature Hercules seated with his club—a depiction that combines Greek artistic styles with local symbolic meanings.

Such artistic representations were not merely decorative. They served as tangible symbols of the interconnectedness of Greek and Eastern cultures. Moreover, they facilitated a shared visual language that helped integrate diverse populations under Hellenistic rule, establishing Hercules as a link between East and West.

Conclusion: Hercules as an archetypal connector

Hercules’ enduring popularity in the Hellenistic Middle East highlights the power of mythology in bridging cultural divides. By embodying attributes that resonated across different traditions, Hercules transcended his Greek origins to become a universal symbol of heroism and strength. His image facilitated political legitimacy and cultural integration, making him a crucial figure in the historical narrative of East-West interactions.