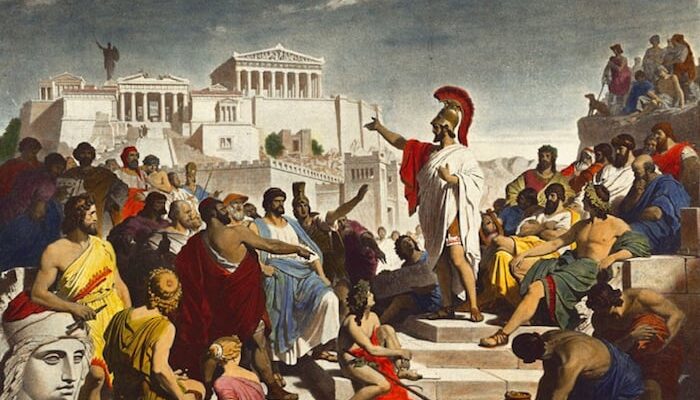

In the US, it is practically a tradition for the losing party to question election results. This was the case with Hillary Clinton in 2016 and Donald Trump in 2020. Concerns about election integrity aren’t new. Ancient Athens ensured election results weren’t rigged by devising systems to prevent corruption in the first place.

Sortition: random selection for election fairness

Athenian democracy stood out for its use of sortition, or random selection of officials. They drew lots for public offices instead of relying on campaigns in which wealth and influence could sway voters.

Aristotle, in Athenaion Politeia, called sortition a true mark of democracy. This method gave all eligible citizens an equal chance at holding office, keeping wealthy individuals from dominating public positions.

Sortition cut down on corruption and manipulation in elections. By relying on chance, Athens minimized the influence of money and power, leading to a more diverse government.

This simple method played a crucial role in keeping Athenian democracy fair. Tridimas, in Constitutional Choice in Ancient Athens (2011), notes that sortition was a powerful tool for reflecting the people’s true will and protecting against election fraud.

The use of sortition also reflects Athenians’ understanding of human nature and the potential for power to corrupt. By removing the incentive for personal ambition in the pursuit of public office, they effectively created a system whereby governance was seen as a civic duty rather than a path to personal gain.

This approach promoted fairness and fostered a sense of shared responsibility among citizens, which is often lacking in modern electoral systems in which political campaigns can be dominated by wealth and special interests.

Ostracism: protecting democracy from election tampering

Athenians also used ostracism to protect their political system. Citizens could vote to exile a person they saw as a threat. Using pottery pieces called ostraka, citizens wrote down the name of the person they believed endangered the state. If most agreed, that person would be exiled for ten years.

Ostracism was a guard against tyranny by preventing one person from gaining too much power. This tool was key to maintaining election fairness and balance in the state. However, the method had its flaws. Influential people sometimes used it to remove rivals.

A famous example was when Themistocles was ostracized (472 or 471 BC), leading him to exile in Argos. His ostracism reflected changing times in Athens, where Themistocles had previously been a prominent figure as a naval strategist and politician instrumental in establishing Athenian sea power.

Tridimas points out that, despite these issues, ostracism aimed to protect democracy from internal dangers. This practice reflected Athenians’ commitment to safeguarding their political system and defending against election manipulation.

Ostracism, while designed to protect the state, also served as a stark reminder of the balance between individual power and collective will that must be maintained in any democracy.

Such a mechanism indicates that Athenians were deeply aware of the dangers of charismatic leaders who might have otherwise amassed too much influence. This preemptive strike against potential tyranny highlights a proactive approach to governance. It is one in which communities take direct action to preserve broader state interests.

Secure voting procedures

Athenians took great care in managing the voting process to prevent fraud in the first place. In the Assembly, where most decisions were made, voting usually happened by a show of hands. This method offered immediate transparency in decision-making. However, when decisions required secrecy, they used secret ballots.

Citizens cast votes using stones or pottery shards marked with various colors to indicate their choice. The method allows people to vote without fear, preserving the process’s integrity. Secret ballots were especially important in legal trials and ostracism decisions in which impartiality mattered. These measures ensured decisions on sensitive matters remained fair.

They also used devices such as the kleroterion to randomly select jurors or officials. This machine added an element of chance to the selection process, reducing the chance of manipulation. Tridimas highlights the kleroterion as an example of how Athens used technology to support democratic principles.

Such innovations were vital in stopping corruption and defending against election tampering. The Athenian approach to securing voting also underscores a commitment to both transparency and fairness. By blending open voting with secret ballots, they balanced public accountability and private conscience.

This dual approach ensured that the process was inclusive and impartial, preventing the kind of behind-the-scenes manipulations that could undermine election integrity. Tools like the kleroterion further emphasize the innovative spirit in defending against election fraud, demonstrating that technology and fairness need not be at odds.

Direct democracy and frequent voting

Athens practiced direct democracy unlike modern representative democracies. Citizens directly participated in decision-making, with the Assembly meeting frequently, sometimes up to forty times a year.

Frequent engagement ensured that decisions reflected the people’s current will. This reduced the risk of long-term manipulation by any one group or individual. Direct democracy also meant political parties, as they exist today, did not exist in Athens. Without parties, organized groups had less of a chance to manipulate elections.

The citizens made decisions together, creating a more equal approach to governance. Tridimas notes that this frequent and direct participation was crucial in maintaining the integrity of Athenian democracy and ensuring election fairness. The Athenian model of direct democracy, with its emphasis on frequent participation, served as a continuous check on power.

By requiring citizens to engage regularly in the political process, Athens minimized the likelihood of any single entity or ideology gaining unchecked control. This system also fostered a strong sense of civic duty and collective responsibility, as governance was not something that happened to the people but rather something they actively shaped.

The absence of political parties further removed the potential for factionalism, ensuring that decisions were made based on the common good rather than party lines or special interests.

How ancient Athens ensured election results weren’t rigged

The US continues to deal with accusations of election tampering, with both major parties often questioning the results. Ancient Athens ensured election results weren’t rigged by creating innovative measures—sortition, ostracism, and secure voting procedures—to prevent election manipulation in the first place.

Although these methods did not always work well, they offer insights into how previous civilizations dealt with corruption and how it has plagued democracies from the beginning.