Collectivism in prior civilizations

Before classical Greece, civilizations like Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Persia thrived on collectivism.

These societies revolved around a central authority, where the community’s well-being precedes individual desires. Leaders like pharaohs and kings embodied the state, and the people’s role was to support this structure.

Individual stories, like the Epic of Gilgamesh, were exceptions, not the norm. However, even in Gilgamesh’s journey, he realizes that his legacy lies not in personal immortality but in the lasting impact he can have on his city, Uruk.

This reflects the broader cultural emphasis on the collective good over individual desires.

In these cultures, myths reinforced the importance of the collective. Even when individuals sought personal glory, their achievements ultimately served the greater good. This focus on the collective created stable, enduring empires.

For example, Egypt’s monumental pyramids symbolize a society deeply committed to the collective effort.

Built not just for the glory of pharaohs but as eternal testaments to the nation’s strength, they represent a society deeply committed to collective effort.

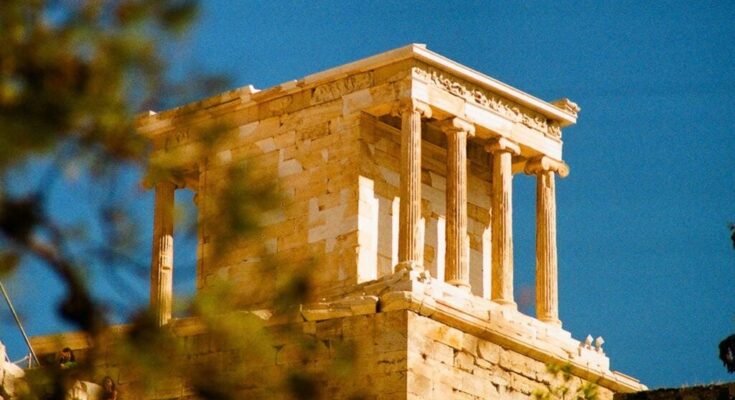

The ancient Greek shift toward individualism

Classical Greece, however, introduced a radical shift. Individualism became the cornerstone of their culture. This shift was most evident in Athens, where democracy took root. In this system, every citizen had a voice.

This participation was both a right and a duty, placing personal responsibility at the heart of governance. Unlike the subjects of pharaohs or kings, Athenian citizens were expected to engage in the political process, debating and voting on laws.

This empowerment of the individual in ancient Greece marked a significant departure from the more authoritarian structures of earlier civilizations.

Greek philosophy further emphasized the individual’s pursuit of knowledge.

Socrates championed critical thinking, encouraging people to question their own beliefs. This focus on individual reasoning was revolutionary, setting the stage for Western thought.

Greek art also reflected this new ideal. Greek artists celebrated the human form and individual expression, unlike earlier cultures’ symbolic and rigid art.

Their works showcased the beauty and complexity of the human experience. Sculptures like those of Polykleitos and Praxiteles captured the human body in its most idealized form.

Furthermore, artists like Exekias included their names on their works for the first time, reflecting a culture that prized the individual.

The disunity caused by individualism

However, this celebration of the individual had its downsides. The Greek Polis, while fostering regional identity, also bred fierce competition. City-states like Athens and Sparta viewed each other with suspicion.

This rivalry often led to conflict, as seen in the Peloponnesian War. The war, a brutal and protracted struggle, not only drained the resources of the Greek states but also weakened their collective defenses against external threats.

Greek city-states frequently allied with external powers to gain an edge over rivals.

For instance, Sparta’s alliance with Persia against Athens during the Peloponnesian War illustrates how outsiders exploited internal divisions.

These alliances highlighted the deep-seated mistrust between Greek states. The emphasis on individual autonomy made collective action difficult. While the Greeks could unite against external threats like Persia, such unity was temporary.

The underlying suspicion and rivalry persisted, preventing lasting cooperation.

A glimmer of hope in ancient Greece

However, a rare moment of Greek unity occurred under the leadership of Macedonia, particularly during the reign of Philip II and his son, Alexander the Great.

Philip II managed to unite the Greek city-states by creating the Hellenic League, a coalition that achieved unity but at the cost of some individual autonomy.

Under this arrangement, Greek states were compelled to follow the directives of the Macedonian monarchy. This was a significant departure from the fiercely independent city-states of classical Greece.

This unity was a welcome development for some Greeks, like the Athenian orator Isocrates.

In one of his speeches, Isocrates urged Philip to reconcile Athens, Argos, Sparta, and Thebes and to focus their collective might against a familiar Eastern foe, much like Hercules had done before him.

Despite the progress under Alexander, who expanded Greek influence across vast territories, the unity was short-lived. Upon Alexander’s death in 323 BC, the empire he had built quickly fragmented.

Short-lived unity and subjugation

Civil strife returned as his generals, known as the Diadochi, fought for control over different parts of his empire, effectively undoing the unity that had been achieved.

This internal discord weakened the Greek world, making it susceptible to external powers. The Romans, recognizing Greece’s strategic and cultural significance, capitalized on this disunity.

Rome established its dominance over Greece by systematically conquering the divided Hellenistic kingdoms. The final blow came in 146 BC with the sack of Corinth, after which Greece was reduced to a Roman province.

The individualism that had once fueled Greece’s greatness now contributed to its downfall, as the fragmented city-states could not resist the might of a united Roman force.

Individualism brought advancement and ruin to ancient Greece

In Sophocles’s wise words, every advancement comes with a curse. Individualism sparked a golden age of cultural achievements that still resonate today. Yet, it also fractured Greece, leaving it vulnerable to external domination. The very thing that brought advancement brought ruin.