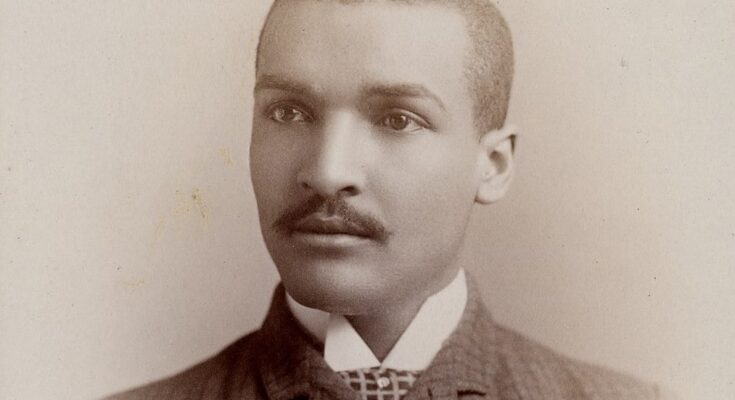

John Wesley Gilbert was a groundbreaking figure in the fields of Classics and Archaeology. During his lifetime, Gilbert, the son of slaves, became a renowned scholar and the first Black person to receive an advanced degree from Brown University.

The scholar, who was an accomplished linguist, classicist, and archaeology, broke countless barriers in his life, making history and leaving behind a complicated and impressive legacy for future generations.

John Wesley Gilbert’s early life and education

Gilbert was born in Hephzibah, Georgia, in 1863, and he was named after the founder of Methodism, John Wesley.

Although his parents were slaves, Gilbert was born free. As a child, he worked as a farm hand while attending public school in Augusta, Georgia.

After completing his primary and secondary education, Gilbert was able to attend college, an opportunity very rarely offered to Black people in the US at the time.

Gilbert enrolled first at the Augusta Institute, a precursor to the esteemed Morehouse College, a historically Black men’s college in Atlanta, Georgia.

A lifelong Methodist, Gilbert later attended the Paine Institute, now Paine College, which was jointly founded by Black and white Southern Methodists. During that time, only Black students attended Paine.

After great success at both educational institutions, Gilbert was offered financial assistance to attend Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

Upon enrolling at the prestigious university, Gilbert became one of the first ten Black men to attend to the school, and he was the third African-American student to receive a Bachelor’s degree there in 1888.

The young scholar was one of the forty African-Americans who graduated from a university in the north in the period of 1885 to 1889.

Shortly after receiving his degree, Gilbert married Osceola Pleasant, who had also graduated from the Paine Institute and received a degree from Fisk University, a historically black university in Nashville, Tennessee.

He was also hired to teach at the Paine Institute, where he himself was educated, in 1888, just a few years before his trip to Greece.

Journey to Athens and work as an archaeologist

An impressive student of ancient languages and cultures, Gilbert was offered a scholarship to study and conduct excavations in Greece by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA) while attending Brown University.

The young student was urged on by Classicist and professor of Greek at Brown, Albert Harkness, who helped found ASCSA.

When he arrived in Athens, Gilbert accomplished another historic first–he became the first African-American scholar to attend ASCSA.

While there, the budding archaeologist amazed his fellow scholars, who applauded his breadth of knowledge. Gilbert was distinguished for “excellence” in Greek while a student at the American School.

While in Greece, Gilbert conducted a series of excavations at the site of Eretria in Evia, a prominent site in antiquity, with archaeologist John Pickard.

The groundbreaking scholar was the first to produce a map of the ancient site.

Gilbert wrote his master’s thesis titled “the Demes of Attica,” now lost, using data and theories developed during his time at ASCSA. It was the first such work written by any American scholar.

George Orfanakos, Executive Director of the American School of Classical Studies, Athens, calls Gilbert’s life and scholarship “quite remarkable,” while speaking to Greek Reporter.

Not only were the scholar’s academic and archaeological accomplishments impressive, but so too were his travels around the country.

As Orfanakos notes, “to get to these places was not like it is today,” and traveling to many of the ancient sites Gilbert visited at the time could be perilous.

Orfanakos highlights the fact that Gilbert’s legacy has inspired many generations of students and faculty at ASCSA.

“Our School has a deep respect for John Wesley Gilbert. Our archivist, Dr. Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan, has researched him quite a bit and posted in her blog about his life and time at the American School. A former student at the American School and now Professor John W.I. Lee from UC Santa Barbara has recently published a book on him…”

“And most recently, two Greek-American Trustees of the American School have named a room in honor of John Wesley Gilbert within the newly renovated student center. His photo, and a brief biography about him, has been placed in the space so that future generations will never forget his name and significant contributions,” Orfankos stresses.

The life and work of Gilbert will even be the subject of an upcoming film produced by the American School, as part of its award-winning series of short documentaries.

Professor John W.I. Lee’s book about the life and work of the groundbreaking archaeologist will be available here in December.

Returning to the US and teaching

Upon graduating with a Master’s degree from Brown University in 1991, Gilbert became the first African-American to receive an advanced degree from the school.

For his impressive scholarship of Ancient Greek, Latin, Hebrew, German, and French, the academic was elected into the American Philological Association, as one of its first Black members.

Gilbert, a religious man who believed strongly in education, returned to his post at the Paine Institute, where he taught the many languages in which he was fluent, after his time in Greece.

According to his students, the archaeologist and linguist was a strict teacher who expected the same hard work and dedication that was required of him to succeed from his own students.

According to those in this classes, Gilbert was known to say:

“If you would like to realize your own importance put your finger in a bowl of water, take it out, and look at the hole.”

The complicated legacy of John Wesley Gilbert

Gilbert embarked on a missionary trip to the Congo with white Methodist bishop Walter Russel Lambuth, who lived in the south, in 1911.

At this point in history, the Congo was a Belgian colony. Its people were subjected to horrible atrocities, including torture, death, and enslavement during the bloody rule of King Leopold II.

Leopold’s reign ended in 1908, just a few years before Gilbert and Lambuth arrived in the country.

Estimates of the death toll during King Leopold II’s rule in the Congo range from one million to 15 million.

Gilbert and Lambuth traveled all across the country and even established a Methodist church and school in the village of Wembo-Nyama, which are both still in operation today.

The missionaries’ work was not appreciated by the colonial leaders of the country. They were wary of the partnership between the two men, one Black and the other white, and feared that they could radicalize the local population into rising up against the colonial powers.

While there is little evidence of a revolutionary curriculum at the school or church, Patrice Lumumba, first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and staunch anti-colonialist, was educated at the school established by Gilbert.

In the years following the establishment of the school, the Belgian colonial leaders no longer allowed Black missionaries to enter the country, fearing that they would turn the people of the Congo against them, and only allowed whites to work at the school.

In a statement that was an expression of a belief that even at the time was controversial, and now seems very outdated, the prominent Black scholar stated that he, and other African-Americans, should evangelize in Africa because they possessed “by nature the race instinct…” and “they are better suited physically for work in Africa than their white brethren.”

Such beliefs caused some instances of friction between Gilbert and prominent Black thinkers.

Yet Gilbert’s ideas and successes had a great impact on African-American political figures and academics that followed him, and he often agreed with many revolutionary African American scholars.

John Hope, first Black president at Morehouse College and founding member of the Niagra Movement, a radical coalition of Black lawyers and thinkers who fought for civil rights, held Gilbert in great esteem.

Surely, countless generations of African-American archaeologists, classicists, and linguists do as well.

Gilbert fell ill in 1921, and passed away two years later in 1923 at the age of 60.