Magic in the ancient Greek world appears predominantly in its mythology in relation to certain gods and demigods, namely Orpheus, Hecate, Circe, and Hermes, who had magical powers.

The demigod Orpheus, the brilliant musician and poet, was the son of the king of Thrace Oeagrus and the Muse Calliope. He was instructed in music by the god Apollo. According to some legends, Orpheus was the son of Apollo and the Muse Calliope. As he grew older, he became a master at playing the lyre and other instruments, and his singing voice was so beautiful that it could charm animals, trees, and even rocks.

The grieving singing of Orpheus’ for the loss of Eurydice was so powerful that it even worked its magic on ferryman Cheron, the guardian dog Cerberus, and the god of the Underworld, Hades, who allowed Orpheus to take Eurydice back to the world of light.

The god Hermes, one of the 12 Olympians, carried a magic wand or staff called a caduceus. He was a messenger and bringer of dreams to both the gods and humans. Hermes was also a mischievous, cunning god and a thief. He worked his magic to help ancient Greece’s most famous heroes and also led the souls of the dead to the Underworld.

The caduceus is an ancient symbol carried by deities as a sign of their power and ability to move between realms. The staff is depicted as a simple stick twined by snakes with wings sprouting from the sides and a sphere at the top.

Hecate and Circe: goddesses of magic

Hecate was the goddess of magic (Greek: Mageia, Μαγεία), witchcraft, the night, moon, ghosts, and necromancy in ancient Greek mythology. She was the only child of Titan Perses and nymph Asteria from whom she received the power over heaven, earth, and sea. Hence, she bestowed wealth and all the blessings of daily life, according to Hesiod’s Theogony.

Hekate assisted Demeter in her search for her daughter Persephone when she was taken to Hades. Hecate guided her through the night with flaming torches. After the mother-daughter reunion, Hecate became Persephone’s minister and companion in Hades.

The goddess of magic was usually depicted in ancient Greek vase painting as holding twin torches. Sometimes, she was dressed in a knee-length skirt and hunting boots, much like Artemis, the goddess of nature and hunting. In statues, Hecate was often depicted in triple form as a goddess of crossroads where she can see in all directions.

Her name means “worker from afar” from the Greek word hekatos. The masculine form of the name, Hekatos, was a common epithet of the god Apollo.

Often depicted as a priestess of Hecate is Medea, the daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis. In the myth of Jason and the Argonauts, she employs her magic tricks to aid Jason in his search for the Golden Fleece. She later marries him, but eventually kills their children.

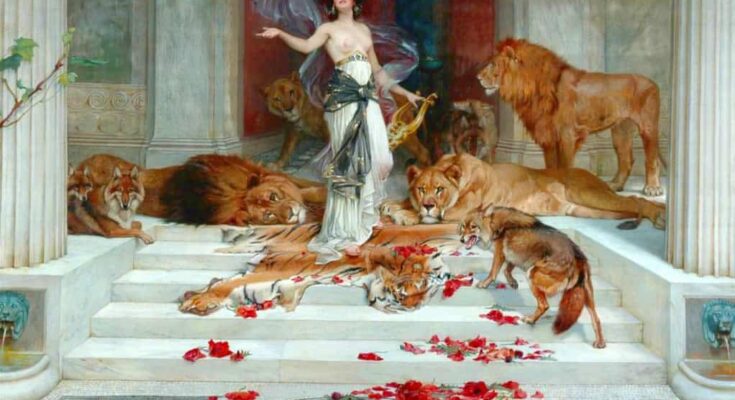

Circe was a powerful sorceress and goddess with an exceptional talent for mixing drugs. She was the beautiful daughter of the sun god Helios and the Oceanid Perseis, as Hesiod wrote in Theogony. Circe lived on the wooded island of Aeaea, and for guards, she turned men into wolves and lions.

The magic powers of Circe appeared in the ancient Greek epic poem Odyssey by Homer. When Odysseus arrived on her island of Aeaea on the way back from the Trojan War, Circe transformed most of his crew into pigs. She seduced Odysseus who lived with her for a year and had sons by her, including Latinus and Telegonus. The hero finally persuaded her to transform his men back to humans.

Magic in everyday ancient Greece

Some individuals in ancient Greek society turned to magic because faith in the gods alone did not seem enough. For immediate results, they used goal-oriented rituals in the belief that the use of magic would satisfy their desires and hopes, or their need to punish an enemy or wrongdoer.

Recent excavations and scholarly analyses of the Greek Magical Papyri reveal the existence of vast sections of magical handbooks, in which ancient professionals disclose detailed recipes and prescriptions for a variety of customary purposes.

Farmers used magic to bring rain and ensure rich harvests, while others performed mystic rites to bear children or bring back a lover who had abandoned them. Yet others had rituals to restore health to an ill family member. Some wore amulets to protect them from disease or danger.

For curse-making, the ancient Greeks used a unique form of hexing known as the “binding spell.” Curses written on lead tablets have been widely documented from as early as the 5th century BC, found in the regions of Sicily, Attica, and the shores of the Black Sea.

The spells were usually carved on small pieces of lead, folded up and pierced with a bronze or iron nail to be buried with a corpse or in the vicinity of chthonic cemeteries.

From the findings, it is unclear if these rituals were a form of traditional self-help in desperate times or were more commonly sought by employing a professional magician to perform the rites. They were often written as letters addressed to underworld deities to summon them through curses.

The earliest surviving evidence for the work of a professional magician in Greece dates to around 400 BC with the discovery of four kolossoi (voodoo dolls) in two distinct graves on the island of Paros, where each doll was punctured by seven nails, enclosed within a lead box and carved with binding curses.

These curse tablets were often written as letters addressed to underworld deities, indicating a tendency to summon gods and goddesses through curses.