Alexander the Great’s (356-323 BC) death meant his vision for a Greco-Persian Empire was extinguished with him—or was it?

A hodgepodge of East and West, Mithridates’ Pontic Empire emerges as a compelling possibility of what Alexander’s empire could’ve been, a faint apparition of that fleeting dream.

Alexander 2.0

Mithridates (135–63 BC) was the inheritor of two cultures and, naturally, an incarnation of two worlds. He delighted in his Macedonian heritage as much as his Persian forbearers.

Claiming Macedonian ancestry on one side and Persian dynastic lineage on the other, Mithridates used his mixed descent to reveal the commonalities between his diverse subjects.

Taking on Alexander’s mantle of global empire, Mithridates envisioned an alternative to Roman supremacy, a new world order.

To achieve this ambitious aim, the Pontian King united his Greek, Anatolian, and Persian subjects under an anti-Roman cross-cultural coalition.

The result of this cooperation was three wars mounted against Rome, wars that escalated to the point of genocide.

How could he amass such a diverse following against such a formidable foe?

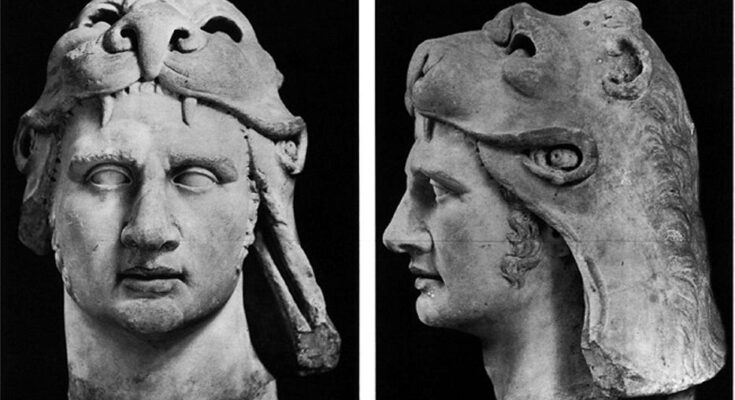

Mithridates took a page from Alexander’s book and embodied East and West, both in appearance and idea.

Pontus: Alexander’s vision of empire?

Mithridates hailed from the Kingdom of Pontus, a cultural melting pot that Alexander the Great would have approved of.

The north of Pontus’s snow-clad Alps was a largely Hellenic-dominated coastline. There, Greek colonists had erected the city of Sinope, Mithridates’ capital.

The historian Strabo, himself a Pontian, claimed that it was “the most noteworthy of the cities in the region.”

South of the Alps was known as Katpatuka (land of horses) by the Iranians and, later, Cappadocia by the Greeks. There, villages predominated apart from a few settlements, such as Amaseia, Strabo’s hometown, and Cabeira.

While Hellenic culture dominated the coast, the Cappadocian hinterland preserved its old Anatolian non-Greek heritage. Rostovtzeff (1932), a pioneer in Pontic history, described the Hellenic influence around the Black Sea as “a thin Greek shell around a hard native kernel.”

The third influence on the region was Iranian. The enduring relics of Persian rule would have been visible to many a Hellenistic Pontian. Strabo says that the Pontic people took sacred vows at the state temple, Zela, which were dedicated to Persian deities: Anaitis, Omanus, and Anadatus.

Moreover, Zeus Stratios, most likely a syncretic reincarnation of Ahura Mazda, received lavish offerings from Persian Kings, which Pontian rulers, including Mithridates Eupator, continued. The continuation of Persian religious customs well after an eclipse of Achaemenid authority attests to the impression Persian presence had made on Pontic royalty and their subjects.

In the subsequent Hellenistic period, the increasing pace of Hellenization of the kingdom meant that the Mithridates Dynasty had to evolve. There needed to be a balance between the new incoming wave of this ancient form of globalization with their Perso-Anatolian traditions that still held sway in their domain.

Divine descent

Mithridates Eupator’s dual lineages afforded him illustrious ancestors and a unique hybrid set of dynastic customs. He was a Helleno-Persian Prince who practiced mixed religious rites.

Mithradates divine connections are well in accordance with Alexander the Great’s own claims. Like the Pontic King, Alexander claimed Heracles and Dionysus, among other numinous figures, as ancestors.

Consequently, the Pontic King embodied redemptive qualities resonating in the Greek and Perso-Anatolian worlds. For the Greeks, he established a mythical connection with Dionysus, the god of liberation and new beginnings, and took the theonym Mithridates Eupator Dionysus.

Likewise, Mithridates claimed heritage from Herakles, who emancipated the titan Prometheus, humanity’s creator. On the other hand, Mithridates’ star-signaling birth was said to fulfill Persian prophecies of a coming savior from the East, as did his name, “Mithras-sent.”

Global principles

In addition to religious mediation, Mithridates weaponized the growing resentment of his subjects. Just like Alexander’s vision for his diverse empire, the Pontian King tried to respect Greek and Iranian values.

Both Greeks and Perso-Anatolians were chafing under Roman occupation. In mainland Greece and Anatolia, the common hatred towards Roman rule provoked a transcultural antagonism against Roman hegemony.

Debt accrued by Roman taxation hindered asa or Truth, a prominent Persian tenet. For the Greeks, Roman occupation was seen as compromising their eleutheria, or freedom, which was fundamental to Greek identity.

Mithridates acknowledged these grievances in his speeches, along with coins and other allusions. By showing sensitivity to both cultures, the Pontian King illustrated how compatible Iranian and Greek cultures could be.

This may be surprising, considering the tumultuous history that plagued the relations between Greeks and Iranians. Egregious crimes were committed in Athens by the Persians and by Greeks in Persepolis at Alexander’s instigation as punishment.

Yet Mithridates successfully harmonized the two cultures, as Alexander the Great’s policies aimed to accomplish.

Was Mithridates’ Pontian kingdom what Alexander’s empire could have been?

Sensitive to Greek and Perso-Anatolian culture, Mithridates entangled much of the Eastern Mediterranean in opposition to Rome. Mithridates carried on Alexander’s vision for an international empire even though he was unsuccessful in his wars against Rome. By doing so, the Pontian king proved Alexander the Great’s Helleno-Persian hypothesis was possible.

Alexander’s vision for joining East and West wasn’t an idyllic dream but was ultimately an achievable reality.