Scientists in China believe they have discovered a new species of vampire squid. This is only the second type of vampire squid known in the world.

Vampire squids can grow to about one foot long. They look scary and have a frightening name, but they are harmless. They live deep in the sea and mostly eat dead animals and waste. Vampire squids do not pose a threat to anything except small sea creatures.

This species has been found in warmer ocean areas around the world, as reported by Live Science. The first and only recognized vampire squid species was officially described in 1903 during a deep-sea expedition led by Carl Chun, a German marine biologist. Several other species were later identified, but they were later determined to be young vampire squids of the same species.

Young vampire squids look quite different from adults, developing a second set of fins near their head as they mature, while their original fins disappear.

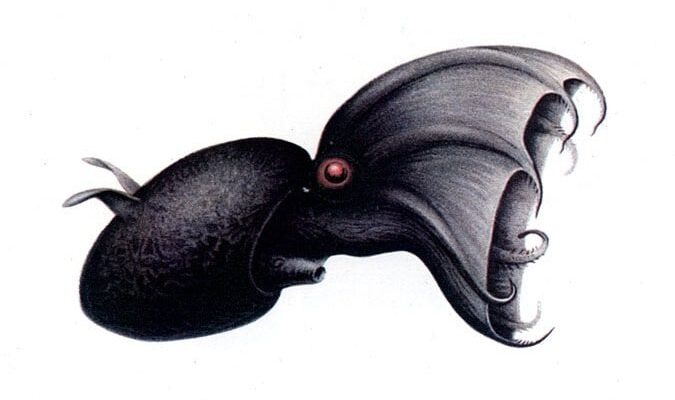

This semi-abstract photo is the webbed arm of Vampyroteuthis, called the vampire "squid" but actually its own group within the cephalopods. When threatened, they curl their arms inside-out around themselves in what has been called a "pineapple" posture. pic.twitter.com/Hez2cjETgm

— Sonke Johnsen (@sonkelab) April 17, 2024

Dajun Qiu, a marine biologist at the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, explained that ten previously identified species actually showed some differences at different stages of their lives. These species turned out to actually be one and the same.

Second species of vampire squid found near Hainan island

In a new study published on May 2nd in the preprint journal BioRxiv, researchers reported the discovery of a second species of vampire squid. Found near Hainan Island, China,= in 2016, it was named V. pseudoinfernalis. This squid was discovered 2,600 to 3,300 feet below the sea surface in an area known as the twilight zone with very little light.

V. pseudoinfernalis has unique features that set it apart from V. infernalis. For example, the positions of its light-producing organs, called photophores, simply differ. In V. infernalis, these organs are a third of the way between the fins and the tail.

In V. pseudoinfernalis, they are about halfway between these points. Additionally, V. pseudoinfernalis has a pointed tail, unlike V. infernalis, which lacks a tail. The new species also has a beak with a longer wing on its lower jaw.

Photographs of the preserved specimen show it looking like a black, gelatinous blob. However, in its deep-sea environment, it probably resembles its cousin with a flowing, cloak-like shape. Genetic analysis supports that V. pseudoinfernalis is indeed a distinct species, noted Qiu.

Qiu mentioned that the plan is to analyze more specimens to confirm that the observed differences are consistent. It is likely that V. pseudoinfernalis has a similar diet to its better-known relative, but further research is still needed.