When Italy attacked Greece on the Albanian front on October 28, 1940, the Hellenic Armed Forces were expecting the move and were well-prepared.

Italy’s preparations for the Greek-Italian War had started as early as 1937. Fascist leader Benito Mussolini, drunk on arrogance and spawned by the subjection of Ethiopia to Italian rule, believed that Greece would be an easy target.

Greek Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas had foreseen Italy’s ambitions and Mussolini’s alliance with Adolf Hitler in the Germany-Italy Axis and started preparing for war.

In the 1936 meeting of the Balkan Entente—the mutual defense agreement between Greece, Turkey, Romania, and Yugoslavia, against attack by another Balkan state (i.e., Bulgaria or Albania)—Metaxas had declared that in the event of a conflict with Italy, he would cooperate with French and British forces.

From November 1937 and onward, Italian foreign minister Galeazzo Ciano, who was also Mussolini’s son-in-law, was preparing for war against Greece.

By early 1939, Greek-Italian relations had reached such a fever pitch that they could only lead to armed conflict.

Italy’s attack plan involved Bulgaria, Serbia

Ciano kept a diary which was found after he was executed for treason in February 1943 and was thereafter used by historians as a valuable historical resource.

On January 8, 1939, Ciano wrote in his diary about his successful talks with Serbia in regards to an attack against Greece: “In agreement with Belgrade to exterminate Albania, possibly facilitating the march of the Serbs to Thessaloniki.”

In talks on the same subject between Italy and Bulgaria on January 26, 1939, there was discussion about Bulgaria’s much-coveted access to the Aegean after taking over Thessaloniki.

On April 7, 1939, Italy occupied Albania, a fact that caused great concern in Greece. On April 9th, the Greek ambassador in London had secretly asked the French and British governments for guarantees in favor of Greece.

On April 13, 1939, France and England announced that they were guaranteeing the territorial integrity of Greece, and the Greek government made the agreement public.

Mussolini reacted strongly. The road works in Albania clearly showed that Italy was preparing to attack Greece.

On May 25, 1939, Ciano, after a long meeting with Mussolini, stressed that the Italian leader openly displayed his hostility towards Greece and Yugoslavia.

On September 20, 1939, a joint supplementary communiqué from Rome and Athens stated that relations between the two countries “continued to be friendly, based on mutual trust.”

Albanians were friendly to the Italians

On May 22, 1940, Ciano visited Albania, stating in his diary “Arrival in Durres and Tirana. Very warm welcome. The Albanians really want the intervention, because they want Kosovo and Chameria. It is easy for us to increase our popularity by exploiting Albanian nationalism.”

On May 23rd, Ciano noted: “Visit to Shkodra and Rubico, a promising copper mine. A warm welcome everywhere. There is no doubt that Italy has won the masses.”

“Our Albanian people are grateful that we taught them to eat twice a day,” he wrote, adding that it was “something that rarely happened before. Even people’s appearance shows this great prosperity.”

On June 10, 1940, Italy entered the war on the side of Germany. Mussolini then warned neutral countries: “I only declare that Italy does not intend to drag into the conflict people that border with us by land or sea. Let Switzerland, Yugoslavia, Greece, Turkey and Egypt take these words into account: it depends on them and only on them.”

But those words rang particularly hollow at the time. The expectation of a war was pervasive among Italian forces stationed in Albania.

On August 12, 1940, Mussolini declared that if Corfu and Chameria were ceded to Italy “without any drop of blood shed,” they would not ask for more.

Greece prepares for the inevitable

In early July 1940, General Konstantinos Platis, the first deputy chief of the General Staff, was arrested because he suggested that Greece could side with the Axis.

On August 15, 1940, the Greek cruiser Elli was torpedoed by the Italian submarine Delfino, commanded by Giuseppe Aicardi, in the waters off the island of Tinos.

The torpedo attack is said to have been ordered by Cesare Maria de Vecchi. The Italian ambassador in Athens, Emanuele Grazzi, however, described it as an act of “shame and piracy.”

From the remains of the two torpedoes, Athens recognized immediately who the perpetrator was, but PM Metaxas decided to keep it a secret. Italy pretended that it was completely unaware of the incident.

At the same time, Italy’s Albanian adviser, a fanatical fascist named Nebil Dino from Chemuria and a personal friend of Ciano, believed that Greece would cede itself to Italy without fighting.

At the end of August 1940, Dino went on a secret propaganda mission to Preveza and Athens and distributed money to a number of Greeks who were friendly to Italy.

The Albanian agent argued that “the Greek people do not seem willing to fight,” that “the Metaxas government is hated by many,” and “the king is neither appreciated nor loved.”

On August 22, 1940, Italy decided to plan an attack on Greece for October 10, 1940 in order to give priority to the war in North Africa in coordination with the German attack on England.

At the same time, Greece had begun a series of war preparations in 1939. At the end of August 1940, the government had laid nets in all ports as blockades, laid down strict rules for airports regarding foreign air services, and called back to arms those men who had already served their military duty.

Around September 10th, the Italian military attaché in Athens, Luigi Mondini, went to Rome to report to the chief of the Italian Armed Forces, General Giacomo Carboni, the reasons why a possible attack on Greece would be pure madness.

On September 28, 1940, the British ambassador to Athens, Sir Charles Michael Palairet, informed London that Chief of General Staff Alexandros Papagos, was ready, if necessary, to fight Italy.

The Italian meeting before the attack

The decisive meeting for the declaration of war against Greece took place on October 15, 1940 with the participation of Mussolini, Ciano, Chief of General Staff Pietro Badoglio and other generals.

Senior Commander of the Armed Forces in Albania, Sebastiano Visconti Prasca, assured the assembly that his soldiers were looking forward to fighting—unlike the Greeks, who had neither armored vehicles nor fighter jets.

According to Prasca, Italy had seventy thousand troops, while the Greeks had only thirty thousand. Mussolini recapitulated the plan: attack Epirus, pressure Thessaloniki, and then advance on to Athens.

In Ciano’s notes, only Chief of General Staff Pietro Badoglio was less optimistic about the prospects for Italy attacking Greece.

The morning of OXI Day

At 3:00 on the morning of October 28, 1940, Italian ambassador Grazzi gave a war ultimatum, which expired in three hours, to Ioannis Metaxas at his home in Kifissia.

The ultimatum said that the Italians wanted to occupy “some points on Greek territory respecting Greek sovereignty over the rest of the territory.”

When Metaxas asked what these points were, Grazzi could not answer because the Italians had not prepared such a list since they did not expect that Metaxas would refuse to surrender the nation of Greece.

The answer, of course, was a resounding “OXI!”

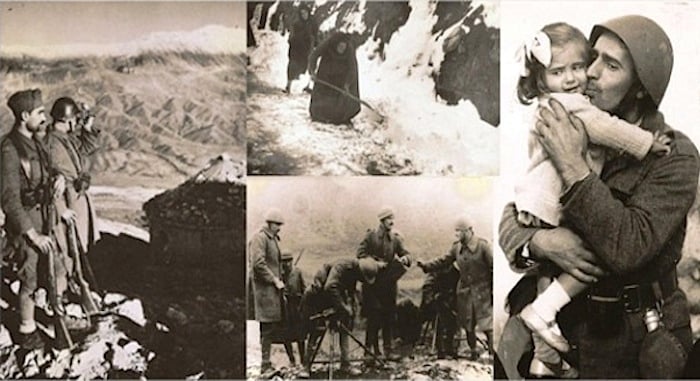

The Greek Army not only repelled the Italians on the Albanian Front but also entered the neighboring country and took back territories that had belonged to Greece.

The failure of Italy to take over Greece forced the Nazis to invade the country months later, wasting men and time they could have used for their main objective, which was to take over Russia, inexorably changing the progression of the war.