Plato, one of the greatest Greek philosophers of all time—with whom one might claim that, along with Aristotle, Greece intellectually conquered the world—traveled widely during his lifetime. Sicily was amongst Plato’s destinations. The question is what was his purpose for his trip to Sicily, and what came of it?

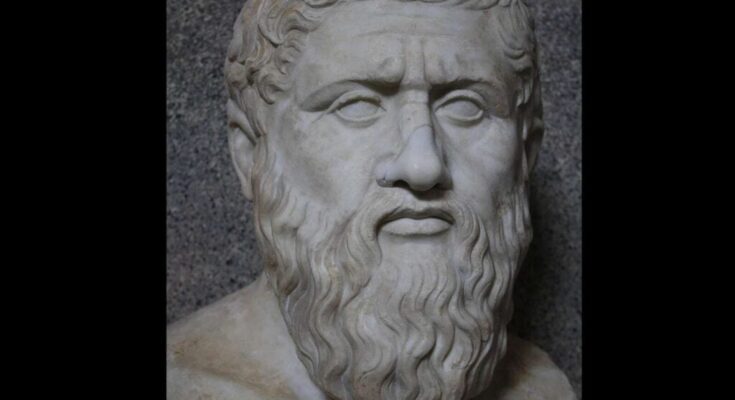

Plato: The man behind the Socratic Dialogues and other legends

He was born in 427 BC. According to Olympiodorus, Plato was of noble origin. His father was Ariston, the son of Aristocles, through whom Plato traced his ancestry to Solon, the lawgiver. His mother, Perictione, was also said by Olympiodorus to be descended from Neleus, the son of Codrus. It is to this heritage that Plato attributes the fact that “with primitive zeal he wrote twelve books on Laws and eleven books on a Republic.”

Olympiodorus relates a legend that was told among the Athenians and the Platonic philosophers of the Academy after Plato’s death. They believed that Plato was actually a philosopher sent by Apollo to mankind to teach them the most Good and Just way of living. According to this legend, an Apollonian specter had a connection with his mother, Perictione, and, appearing to Ariston in the night, commanded him not to sleep with Perictione during her pregnancy.

The Neoplatonic philosopher Proclus talks of:

“…those perpetual attendants of a divine nature called essential heroes. These are impassive and pure, and the bulk of human souls who descend to earth with passivity and impurity. It is necessary that there should be an order of human souls who descend with impassivity and purity.

These souls were called by the ancients terrestrial heroes on account of their high degree of proximity and alliance to such as are essentially heroes. Hercules, Theseus, Pythagoras, Plato, etc., were souls of this kind, who descended into mortality both to benefit other souls and in compliance with that necessity by which all natures inferior to the perpetual attendants of the gods are at times obliged to descend.”

Plato’s early education

When he was a young man, Plato first went to Dionysius, the grammarian, for the purpose of acquiring common education. He mentions Dionysius in his dialogue The Lovers so that even Dionysius, the schoolmaster, might not be passed over in silence by Plato.

After him, Plato employed the Argive Ariston as his instructor in gymnastics from whom it is said that he derived the name of Plato. Prior to this, he was called Aristocles after his grandfather. He was supposedly called Plato because of the broadness of his chest and forehead, as statues of him reveal.

According to others, however, they called him Plato due to the ample and expansive character of his style.

Plato’s music teacher was Draco, the son of Damon, and he makes mention of this master in his Republic. The Athenians instructed their children in three arts—grammar, music, and gymnastics—and this, it seems, was with great propriety. They taught them grammar to adorn their reasoning, music to tame their anger, and gymnastics to strengthen the weak tone of desire.

Plato’s path to philosophy and his life prior to Sicily

Before beginning his philosophical journey, Plato was first an artist and poet. He composed tragic and dithyrambic poems, along with other poetical pieces, all of which he burned as soon as he began associating with Socrates. At the time, he reportedly quoted the verse: “Vulcan! Draw near; ’tis Plato asks your aid.”

Nietzsche, the German philosopher who was a fierce critic of Socrates, wrote while cursing Socrates’ influence on Plato that had it not been for his influence, Plato would have “become a tragedian that would have surpassed both Aeschylus and Sophocles.”

Pausanias narrates in his Attica:

“Not far from the Academy is the monument of Plato, to whom heaven foretold that he would be the prince of philosophers. The manner of the foretelling was this: On the night before Plato was to become his pupil, Socrates had a dream in which he saw a swan fly into his bosom. Now, the swan is a bird with a reputation for music because, they say, a musician by the name of Swan became king of the Ligyes on the other side of the Eridanus beyond the Celtic territory, and after his death, by the will of Apollo, the Gods transformed him into the bird.”

Most people today view Plato as a great contributor to philosophy, largely due to the fact that he preserved the sayings of Socrates. Indeed, Socrates was the one who “opened fire” to challenge peoples’ views, but Plato was the one who spread these ideas far and wide. Though it is true that in most of the Platonic dialogues Socrates is the protagonist, it would be a grave mistake to view Plato as merely “Socrates’ secretary.” In reality, many things that Plato attributes to Socrates in the dialogues are actually his own views and thoughts, attributed to his tutor out of respect.

This is why Diogenes Laertius tells us:

“They say that, on hearing Plato read the Lysis, Socrates exclaimed, ‘By Heracles, what a number of lies this young man is telling about me!’ For he has included in the dialogue much that Socrates never said.”

Diogenes Laertius also tells us that Plato’s philosophy is a mixture of older philosophical theories, for regarding his views on the world of the senses, he is in agreement with Heraclitus. When it comes to Intellect, he agrees with Pythagoras, and in matters of politics, he aligns with Socrates.

The Greek philosopher’s vision of justice: The republic

But what was it that actually drew the young man so close to Socrates in political matters? What made him honor Socrates to such a degree?

The answer lies within the most well-known and influential book ever written by Plato, the Republic. This work, consisting of ten books, was originally titled On Justice. In the first two books, Socrates debates other philosophers on the true nature of justice. This concept was far from clear for ancient Athenians. Instead, it has been a subject of intellectual conflict from antiquity to modern times.

He disagrees with the traditional view of justice, which had been the mainstream belief in ancient Greece since Homer, and tries to establish an objective perspective on what justice actually is. The first opinion on justice, as expressed by Polemarchus and Adeimantus, was that justice consists of “benefiting your friends and harming your enemies.”

The second view, expressed by the sophist Thrasymachus, claimed that:

“…justice is nothing but the advantage of the strongest” (those in power in all polities). He expressed the position that being unjust (i.e., benefiting yourself at the expense of others) is more beneficial than justice.”

Arguing against both of these points, Socrates claimed that “a just man can never harm, only benefit” and “justice is about the stronger benefiting the weaker.” He further argued that, in order for a man to be truly happy, he must be just, and that justice is an end in itself. In contrast, unjust people are actually unhappy even if they seem successful in achieving their goals.

A just republic would be analogous to a human soul

To convince his interlocutors in the dialogue, Socrates, over the next books of the Republic, tries to establish and imagine what a perfectly just polity would look like. This would be a form of government organic in nature, meaning that the citizens belonging to it would prioritize collective interest above individual interest.

In fact, Socrates made a parallel between such a society and the human soul. According to him, the human soul consists of three parts: the rational part, the irrational part, and the appetitive (or vegetative) part. The first part is responsible for intellect, the second for emotion, and the third for material desires. Socrates claimed that justice consists of a person getting these parts of the soul to work in harmony. In this harmony, the rational part is in control.

Using this analogy, Socrates argued that his ideal polity would function similarly.

It would be a body where the rational part (the best citizens) would govern and seek to unite the entire society just as the mind unites the organs of the body, from the head to the hands and legs. Every part functions for the benefit of the whole, according to its role. The best citizens in this city would be those who excel in virtue and would actually rule as philosophers. This is why Socrates called this form of government an “aristocracy” (literally meaning “rule of the best”).

He divided the polity into three classes, each reflecting a part of the human soul. The philosophers would form the ruling class, representing the “rational” part of the polity. The second class would consist of the guardians, the warriors of the polity. This would correspond to the “spirited” (or emotional) part of the soul.

Lastly, the producers, the vast majority of the people, would be focused on satisfying their material needs, having families, and owning property. The rulers of this polity would ensure that the producers have sufficient goods to meet their needs.

The philosopher-king of the Republic

The class of philosophers would be educated from youth by society and would not even know their parents. The reason for this is that Socrates wanted them to view all the elders of their class as their parents and all the other young men and women as brothers and sisters.

Everything in that class would be common and belong to everyone, while gifted women would receive equal education alongside philosophers and warriors. Children would also receive a shared education. Socrates claims that youth should learn through games. The polity prohibited any form of violence towards them. That is because he believed it is impossible to shape a soul through force.

From this class of individuals, the “king” of the Republic would arise—a philosopher-king who, in addition to governance and the art of war, would be an expert in mathematics, natural sciences, music theory, and, above all, dialectic.

For Socrates, dialectic is the science of sciences. He deemed it as the ability to discover the unity and common foundations of every branch of knowledge within a system of thought that is incorruptible. If a candidate fails to excel in even one of these areas, they reject him. The ideal king should not possess private property. He should abhor power and rule solely through service. Therefore, the more excellent philosophers there are, the better because the burdens of exercising power will be divided into shorter intervals.

Socrates claimed that this polity would be an analogy to the heavenly order. He believed that, just as in the starry heavens, the brightest stars preside over the dimmer ones. The Sun rules over the planets, the Moon, and the Earth. Similarly, the Republic would reflect a similar hierarchy. The philosophers, being the most divine individuals, would reflect the Sun. The guardians would represent the Moon, while the producers are instead likened to the Earth.

The allegory of the cave and the world of forms

While Socrates described this polity to his friends, Glaucon, Plato’s elder cousin, questioned his statements. He asked if such a polity could ever exist. Socrates replied that a just man ought to follow the principles of such a polity. Striving toward this ideal would accomplish much in that direction.

This leads to Socrates introducing the Allegory of the Cave. In this allegory, Plato has Socrates describe a group of individuals who live their entire lives chained to the wall of a cave, facing a blank wall. These people observe the shadows cast on the wall by objects passing in front of a fire behind them and give names to these shadows. For the imprisoned, these shadows represent reality.

Socrates explains that the philosopher is like a prisoner who has released himself from the cave. Such a man understands that the shadows are not the true reality. The philosopher comprehends the true form of reality, distinguishing it from the fabricated reality represented by the shadows.

The prisoners do not wish to leave their prison because they are unaware of a better life. One day, they manage to break their bonds and discover that their reality is not what they thought.

They encounter the sun, which Plato uses as a counterpart to the fire behind them. Just as the fire casts light on the cave walls, the human condition remains captive to the impressions created through the senses. These sensory perceptions bound us, and we are unable to see beyond them.

Even if these interpretations are a distorted view of reality, individuals cannot free themselves from the shackles of their condition. They cannot escape their apparent state, just as prisoners could not break free from their chains.

The people of the cavern are actually us

However, if a person could miraculously escape from their slavery, they would find a world that is initially incomprehensible to them. The sun would be bewildering to one who has never seen it. In other words, they would discover another “realm,” an unfathomable place. This would be the source of a higher reality than the one they have always known.

Socrates explains that the prisoners in this cavern are representative of us mortal men. We all live in the world of senses, the material world where everything seems to be the only reality that exists. In truth, however, this is merely an idol of the real that a higher source created. Just like a piece of art, a painting reflects what lies within the soul of the artist.

Using this allegory, Plato has Socrates discuss the world of Forms or “Ideas.” As Pletho Gemistos explains, according to this theory, its proponents:

“…do not suppose that God, in his absolute perfection, is the immediate creator of our universe, but rather of another prior nature and substance, more akin to himself—eternal and incapable of change in perpetuity. God did not create directly by himself but through that substance. This substance comprises an intelligible order. From this order arise the perfect forms or archetypes of everything that exists in the material world.”

For example, when we speak of “man,” we refer to many different kinds of people. Similarly, when we talk about animals like wolves, goats, or even trees, plants, tables, and buildings, we consider different species and individuals of each, each with its own traits. However, the cause of their existence and plurality lies in the intelligible order of divinity, where the ideal archetypes of each are more perfect and beautiful and are also incorruptible. These archetypes are what Plato calls “ideas.”

Plato’s trip to Sicily and his political aspirations

However, Plato didn’t just attribute the theory of Forms to Socrates arbitrarily. He aimed to address the Idea of Justice itself. The form of Justice also exists in the “Ideal World,” while manifesting itself in various forms in our world. This was the purpose of the Republic: to reveal what constitutes justice itself, from which everyone would benefit. The polity in this work represents “Justice” for Plato.

This leads us to Plato’s decision to travel to Sicily and meet Dionysius. As he writes in his 7th Epistle:

“While at first I was filled with eagerness for political action, as I watched everything turn upside down, I was ultimately overcome with dizziness. Of course, I did not cease investigating how it might be possible to correct all that I mentioned, particularly the state in general.

However, I always awaited the right moment for action. Ultimately, I realized that none of our contemporary states is governed properly. Their legislation is, one might say, in a condition that cannot even be healed without serious preparation and the aid of some extraordinary fortune.

Thus, I was compelled to extol true philosophy, asserting that through it, one can see justice everywhere—in the state as well as in individual lives. Consequently, generations of people will continue to suffer unless either those who truly and correctly philosophize take political power into their hands, or political leaders, by divine decree, truly philosophize.”

Tyranny, the worst polity but also the way for the Republic: Dion could be a just ruler?

That is why, Plato in his 7th epistle, feeling outraged by the assassination of his friend and student Dion of Syracuse in Sicily, says:

“These people, by killing the one who wanted to exercise justice, have, despite having immense strength, never wished to apply justice throughout the extent of their power.

If philosophy and political authority had truly united within that power, it would have illuminated all people, Greeks and barbarians alike. It would have clearly shown everyone the right idea: that neither a country nor any individual can ever be happy if they do not live their life with knowledge under the dominion of justice, whether they possess it within themselves or have been raised and educated in the morals of virtuous guides.”

Plato believed that Dion would apply laws to Sicily according to his theories. He believed that if he did, he would show the whole world what justice actually is. Plato’s polity did not support tyranny. In reality, he saw tyranny as the exact opposite of his “aristocracy.” He regarded tyranny as the most unjust and unhappy form of polity.

Nonetheless, he believed tyranny had something in common with his philosopher-king: both acted above written rules and laws. The only difference was that the philosopher-king would act for the sake of justice and the whole of society unlike the tyrant who would act for his own benefit alone.

He believed that only justice leads to happiness. This implies that for a ruler—or anyone—to choose injustice over justice would be due to ignorance. This was in accordance with the teachings of Socrates. No one wants to harm themselves through ignorance of their true interests unless they are mad. In his view, the only way to make someone just is to remove their ignorance. In this way, a tyrant could become a philosopher-king.

Plato’s three trips to Sicily, the application of Plato’s theories

Plato traveled to Sicily three times. As Diogenes Laertius informs us:

“The first time, when Dionysius, the tyrant of Hermocrates, compelled him to mix with him. While discussing tyranny and asserting that it was not better for him to only benefit himself unless he also differed in virtue, he was met with resistance. For Dionysius, enraged, said, ‘Your words are of an old man,’ and added, ‘But yours are tyrannical.’”

As Plato had become indignant, the tyrant of Sicily first attempted to kill him. However, persuaded by Dion and Aristomenes, he did not go through with this but delivered him to Pollis, the Lacedaemonian. Pollis had arrived as an ambassador at the right time to receive him. He took Plato from Sicily to Aegina and sold him as a slave in Cyrene. Anniceris liberated him of Cyrene for twenty minae. He sent him back to Athens to his friends.

The second time Plato traveled to Sicily, he went to the younger Dionysius, asking for land and that the people live according to his polity. However, he did not do this, despite promises. Some say Plato even risked his life persuading Dion and Theodotus about the freedom of Sicily. When Archytas, the Pythagorean, wrote a letter to Dionysius, he urged him to save himself and escape to Athens.

Thirdly, Plato returned to Sicily to negotiate between Dion and Dionysius. Nevertheless, he did not return empty-handed to his homeland. There he did not touch the polity, although he was a statesman, according to what he had written. The reason was that the people were already accustomed to different political regimes.

Final days of Plato’s life

Plato abandoned every trial to occupy himself with politics after his last return to Athens from Sicily. He opened his philosophical school, the Academy. We learn from Olympiodorus that he decided to spend his time there alone as much as possible. He passed away in 347 BC at the age of eighty.

According to a manuscript, he died while listening to flute played by a Thracian girl and simply quietly slept. This was a most suitable death for an artist-philosopher, and he was a musician up to the very last moments of his life. Indeed, he was a man who combined philosophy and poetry, one who to this day guides his readers in seeing the world in an artistic way. As Nietzsche would say, it takes an artist like Plato to hate this world so much that he would look into the “ideal” as inspiration for a better one.

Olympiodorus narrates that to his tomb, the Athenians inscribed the following epitaph:

“From great Apollo paeon sprung. / And Plato too we find. / The savior of the body one. / The other of the mind.”