Pontius Pilate, the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, is inextricably connected with the prosecution and trial of Jesus Christ, yet his later life has been subject to lore and religious myth.

While the Roman prefect was a central figure in one of the world’s best known stories, there is little actual knowledge of the man’s life and character following the crucifixion of Christ.

There is historical evidence that Pontius Pilate governed Judaea from approximately 26 to 36 AD, but very little is known of his previous life. In 1961, archaeologists in Caesarea discovered hard evidence of Pilate’s rule. It was a fragment of a carved stone with Pilate’s name and title inscribed in Latin and was found face down, being used as a step in an ancient theater. It had likely served as a dedication plaque for another structure.

Further evidence of Pontius Pilate’s term as Judaea governor was his name inscribed in Greek on a 2,000-year-old copper alloy ring excavated from Herodium. The discovery was mentioned in a November 2018 article in the Israel Exploration Journal.

Pontius Pilate as Judaea’s ruler

Pilate was appointed by Emperor Tiberius and protected by Roman army officer Sejanus. What we know of him as a ruler of Judaea is from accounts of Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BC-50 AD) and Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (c. 37-100 AD). They both paint a picture of a ruler who was not liked by the Jews. He was considered cruel and greedy.

The Judaea prefect incited their fury by issuing coins with symbols of the pagan gods and hanging icons of Emperor Tiberius in Jerusalem and other towns across the province, actions which the Jewish people deemed idolatrous.

It is said that Pilate’s weak personality and lack of diplomatic skills often led him to resort to cruelty to resolve difficult issues such as civil upheavals.

Throughout his governance, he faced constant uprisings and unrest. At one time, he sparked a riot over his appropriation of Temple funds to build an aqueduct. His use of brutal force to suppress these revolts further strained relations with the local population. These actions brought Pilate under scrutiny from higher authorities in Rome.

The trial of Christ

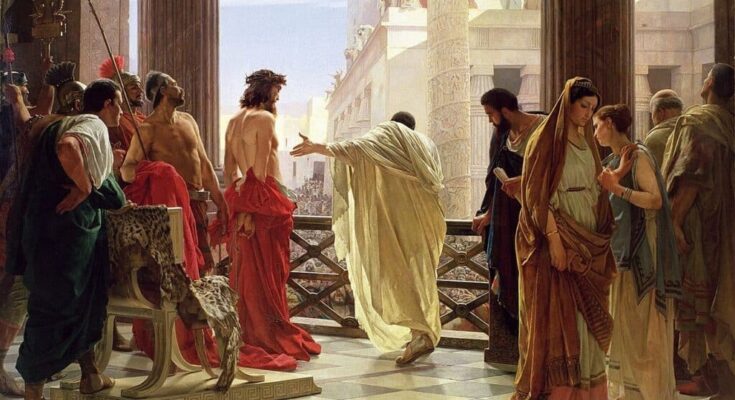

The New Testament suggests that Pilate was a weak, indecisive ruler, hence his capitulating to the mob’s loud request to crucify Jesus and release the thief Barabbas. However, his decision was mostly due to his need to placate the powerful priests of the Jerusalem Temple.

In his Gospel, Matthew presents the famous scene of Pilate washing his hands, which in later history became a metaphor for avoiding responsibility.

When Pilate saw that he was getting nowhere and an uproar was igniting in the crowd, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd. “I am innocent of this man’s blood,” he said. “It is your responsibility!” (Matthew 27:24).

Throughout his rule, Pilate struggled to balance Roman authority with the religious sensitivities of the Jewish people. The continuous tensions eventually led to his downfall and recall to Rome in 36 AD.

Pontius Pilate following the crucifixion of Jesus

According to Josephus and the Roman historian Tacitus, Pilate was removed from office and sent back to Rome after using excessive force to suppress a suspected Samaritan insurrection at Mount Gerizim.

Information on the life of Pontius Pilate after the crucifixion of Christ is shrouded in mystery and myth, with nothing said about it in the New Testament.

Once he returned to Rome, Pilate practically vanished from historical record. According to some traditions, he was executed by the Emperor Caligula for his bloody suppression of the revolting Samaritans. Other traditions have him committing suicide, throwing himself into the Tiber River. The early Christian author Tertullian even claimed that Pilate became a follower of Jesus and tried to convert the emperor to Christianity.

Based on 2nd century documents by pagan philosopher Celsus and the Christian apologist Origen, most modern historians believe Pilate simply retired after discharge from his duty in Jerusalem.

Pontius Pilate’s wife, Prokla, and her sainthood

In Matthew 27:19, when Pilate was faced with the crucial dilemma of condemning Christ in front of the furious mob, his wife sent him word about a revelation she had in a dream about Jesus. She urged him to “have nothing to do with that innocent man,” and Pilate relinquished his responsibility to the emperor.

According to Christian tradition, an angel visited her in her dream and told her that Christ was innocent.

The cognomen Procula (in Latin) or Prokla (in Greek) for Pilate’s wife first appears in the Gospel of Nicodemus.

An early church tradition that had taken a favorable opinion of Pilate persisted in some churches into the early 21st century. He and his wife—unnamed in the New Testament but identified in the Apocrypha as Procla or Procula—are venerated in the Eastern Catholic Church and the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. Their feast day is June 25th.

In the Greek Orthodox Church, the feast of St. Claudia Procula (Greek: Αγία Πρόκλα) is observed on October 27th.