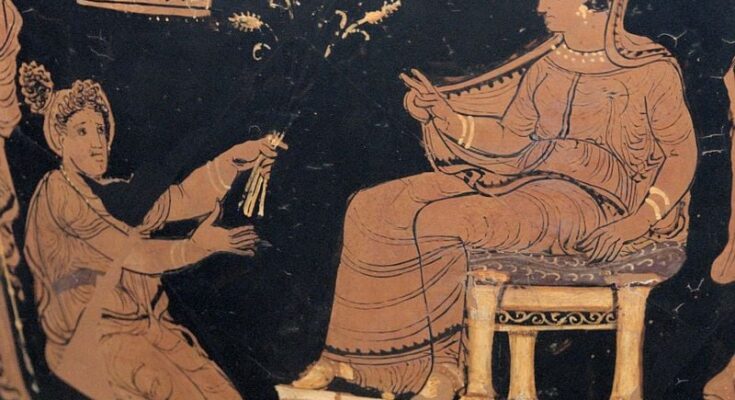

Priestesses in ancient Greece had powers that elevated them to a relatively high status in society.

In the majority of ancient Greek city-states—with the notable exception of Sparta—the way women were treated was, at the very, very least, that of a second-class citizen.

However, one area of society allowed females to hold positions of esteem and allowed them a degree of personal freedom.

In her seminal work “Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece,” Joan Breton Connelly argues that religious roles served as an “arena in which Greek women assumed roles equal…to those of men.”

This stood in marked contrast to the many strictures under which women lived their lives in those times. Rarely allowed to leave the home, women had little or no choice in whom they married and they could own no property whatsoever. They were typically married off in their teenage years.

Women were not asked their opinion on any matter outside the home, and, of course, they could not vote despite the existence of an early form of democracy in ancient times. They were expected to devote themselves purely to household tasks and the raising of children.

Priestesses essential for the serving of the Greek goddesses in rituals

Usually depicted with their heads down—showing their modesty in not daring to even gaze at any male that might be near them—in contrast to the straightforward gazes of male figures, women in ancient Greece were the very picture of subservience.

However, in that world, there were also many goddesses to be served, and that meant priestesses had to do the honors.

Hiereiai (singular: hiereia) was the title of the female priesthood or priestesses in ancient Greece. According to the religious demands of ancient times, there were a number of different offices by which the formal worship of gods and goddesses had to be carried out.

Both women and men functioned as priests, and both even received pay for their services. While there were local variations depending on the cult in question, the Hiereiai had many similarities across the Greek world at that time.

Women who participated in the official worship of goddesses were respected figures, who served as role models and were often given property in direct contravention of Greek law. Incredibly, some of them even became celebrities and had statues erected in their memory.

State funerals, political power were perks for ancient Greek priestesses

Connolly’s work shows that these female religious figures also had enormous state funerals, and were, perhaps most amazingly, even consulted on political issues of the day. In most important respects, therefore, they were essentially seen as the equals of men.

Other benefits enjoyed by priestesses included not being taxed, having bodyguards, having reserved front row seats at competitions, and legal benefits that women rarely had in those times.

Unlike the later Roman priestesses, the vestal virgins, who devoted themselves to the worship of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth, who had to remain abstinent for thirty years, no one in ancient Greece expected their female religious leaders to remain chaste.

Priestesses could marry and have children, and some positions even required they be married.

On the rare occasion a goddess cult called for their priestess to remain celibate, they usually selected much older women for these roles.

A position of priestess could be inherited, purchased, or even won by election.

By all accounts, the job kept ladies busy, as there were 170 annual festival days in Athens, with women participating in 85 percent of them. Even on ordinary days, jobs carried out by priestesses might include sacrificing animals, leading public prayers, and carrying holy items in processions.

Oracle of Delphi, or Pythia, most important priestess of them all

The most powerful priestess of them all in ancient Greece, the Oracle at Delphi, even foretold the future.

Of course, given the very stratified nature of society those days, priests and priestesses were normally chosen from among the elite class and the aristocracy since these offices conferred great prestige.

As hard as it may be to imagine given the extremely subservient role of most women in that era, priestesses were considered to be officials of the city, and their office was considered an honor and spoken of with great pride by the woman’s family.

In order for her to fulfill her duties, a priestess must have been educated to a certain degree, and the daughters of aristocratic families were eligible to be the only females to receive an education in those times.

Normally, goddesses were served by priestesses, as the Greek gods were served by priests. The virgin goddess Artemis was, naturally, served by young virgins, while Zeus’ wife, Hera, the goddess of marriage, was served by married women.

Usually, a priestess served only for a limited time; this state was never meant to be perpetual in most cases. This was especially true of virgin priestesses. Priestesses who were required to be unmarried virgins during their tenure served for a limited time prior to marriage and often only for a single year.

The priestesses serving the goddesses Athena Alea of Tegea, Artemis of Aigeira, Artemis Triklaria of Patrai, Artemis of Ephesus, and Poseidon of Kalaureia all served only for a short time prior to reaching adulthood and marrying. In contrast, the priestess of Heraion of Argos, who was a married woman, served the married goddess Hera for the rest of her life.

The most well-known of all the woman who served as the Oracle of Delphi, or Pythia, was chosen in middle age after having lived what was generally seen as a blameless life.

The historical Diodorus explained how, initially, the Pythia was an appropriately clad young virgin. In the earlier years of the Oracle, great emphasis was placed on her chastity and purity, sine she was meant to be reserved for union with the god Apollo, who was worshipped at Delphi.

However, the situation changed, as it so often does in Greek mythology, due to the behavior of mortal men. One story has it that:

Echecrates the Thessalian, having arrived at the shrine and beheld the virgin who uttered the oracle, became enamoured of her because of her beauty, carried her away and violated her; and that the Delphians because of this deplorable occurrence passed a law that in the future a virgin should no longer prophesy but that an elderly woman of fifty would declare the Oracles and that she would be dressed in the costume of a virgin, as a sort of reminder of the prophetess of olden times.

The priestess was the keeper of the keys to the temple. She was also the caretaker of the cult statue of the temple. She officiated at sacred rituals, presided over and led rituals of worship, and performed ritual sacrifices of animals.

Types of Priestesses, or Hiereiai in ancient Greece

The Basilinna (Greek: Βασιλίννα) or Basilissa (βασίλισσα), both titles meaning “Queen,” a ceremonial position in the religion of ancient Athens, was held by the wife of the archon Basileus. This role dated back to the time when Athens was ruled by kings, and their wives thus acted as priestesses. The duties of the basilinna are described in the pseudo-Demosthenic speech “Against Neaira,” given by Apollodorus of Acharnae, which is the main source of evidence about the position.

The speech is especially significant since it is the fullest extant narrative of the life of a woman in the classical period. It is valuable for what it says about women and gender relations in the classical world. Accordingly, today, it is frequently used in teaching about Athenian law and society.

The laws which set out the qualifications for a basilinna were inscribed on a stele which stood in the sanctuary of Dionysus at Limnai. She was expected to be of Athenian birth and not previously married.

The most important duty of the basilinna appears to have been taking part in a sacred ritual marriage to the god Dionysus as part of the Anthesteria. This ceremony seems to have taken place at the Boukoleion near the Prytaneion.

Most scholars believe that this would have happened on the second day of the festival of “Choes.” However, others say it in fact happened on the first day of the festival called “Pithoigia.”

The basilinna was also responsible for administering an oath to the gerarai, the female priests who had apparently been appointed by the archon basileus. This took place on the second day of the Anthesteria. Some experts argue that it must have taken place after the wedding.

Gerarai (Greek: Γεραραί), also known by the latinized form Gerarae, were priestesses of Dionysus (who was called Bacchus by the Romans) in ancient Greek ritual. They presided over sacrifices and participated in the festivals of Theoinia and Iobaccheia that took place during the month of Anthesteria among their other duties.

Numbering fourteen, they were either sworn in by the Athenian basilinna or her husband, the archon basileus. One of their primary duties during the Anthesteria was to assist in performing the sacred marriage rites of the queen to Dionysus, and thus, they were held to complete secrecy. According to a folk etymology, they were called Gerarai, from the Greek word γηράσκω, gerasko, “I grow old,” because older women were chosen for this role.

The Peleiades (Greek: Πελειάδες, “doves”) were the sacred women of Zeus and the Mother Goddess, Dione, at the Oracle at Dodona. Pindar made a reference to the Pleiades as the “peleiades” a flock of doves.

The chariot of Aphrodite was drawn by a flock of doves as well.

According to Atlas Obscura, the Heraean Games, dedicated to the goddess Hera, were just like the males’ athletic competitions, and they were held every four years. It’s not clear when or why they began, but they may be almost as old as the Olympics.

A total of sixteen women from various city-states competed in footraces. Unlike the males who took part in their athletic contests, the women wore tunics, although they were cut very short and only covered half their chests. The winners received olive branch headdresses, as well as part of a dead cow. Statues with their names carved on them were dedicated to them. Women from Sparta, who were encouraged from birth to be tough and engage in sports, apparently won much of the time.

Although none of the statues depicting the victors of these female games have ever been found and there is scant evidence of them in the historical record, that doesn’t mean they didn’t take place, since females as a rule were viewed as socially insignificant at that time.

The great annual festival of Thesmophoria

According to the researchers at the Oxford Research Encyclopedias, female-only religious festivals like Thesmophoria, which banned men completely, were an important part of life in ancient Greece.

And the social release granted to women of that era, along with the power they had as they engaged in the religious rituals that were part of the feast, must have made them feel as if they had at least a little power of their own for once.

Male citizens were even required by law to pay all expenses so that their wives could attend the Thesmophoria. Sadly, single young women were not allowed to take part. Like many other religious rites involving women, it revolved around fertility and agriculture, as it related to plant fertility.

The three-day festival took place yearly in the fall, and in Athens, there was even a dedicated spot for it near the men’s assembly, which women essentially took over for their own use. It was the closest they would get in those times to the dazzling world of ancient Greek politics.

The Thesmophoria were festivals dedicated to Demeter, the goddess of harvest and fertility, and her daughter Persephone, to whom women would make sacrifices. This female-only annual festival may have been celebrated as early as the 11th century BC.

The three-day fest took place in the Greek month of Pyanepsion, (our October). During the festival, women went to live in huts, outside of the city giving them a bit of a feeling of independence, at least.

During the first day of Thesmophoria, called Anodos, (which means “uprise”) they buried the carcasses of pigs in a large pit in the ground. From this same pit, they would ritually bring up the carcasses they had buried the year before.

This is thought by scholars to be related to the myth of Demeter and her daughter Persephone, who was abducted by Hades and was forced to live underground. In addition, it was part of the necessary rituals to bring about fertility from the earth every year.

The second day was called Nesteia, or fasting. The women fasted and ate only pomegranate seeds on that day. They, acting in the role of priestesses, would then mix the rotten pig flesh from last year’s carcasses with more seeds, and place the mixture on an altar.

Interestingly, the women were banned from speaking on that day as well. The silence of the second day is believed to reflect Demeter’s mourning for her daughter. However, at sunset, the ladies’ fasts would be broken with ritual cakes that had been made into the shapes of female genitalia.

To top off the evening’s frivolity, the women would break their silence as well by making ritualized obscene jokes about men. But again, there was great significance in this as well, as the jokes were to commemorate Iambe, the servant who tried to cheer up Demeter when she was bereft over the loss of Persephone.

Perhaps this is not one of the more usual traditions one would associate with ancient priestesses, but it is also one which undoubtedly made them feel that they at least had the power to speak about their lives and their men—which, for all intents and purposes, they didn’t normally have, as they stayed in their homes with them twenty-four hours a day.

The third day of Thesmophoria was called Kalligeneia, meaning “fair birth,” reflecting the all-important fertility of women. The women sang ritual songs on that day of the festival. The older women taking part would approach the altar to remove the mixed pig flesh and seeds, and then each woman would ritually bury a part of it in the fields.

As we understand the festival today, we see that death, or winter, is personified by the dead pigs and the rebirth of life every spring is represented by seeds.

Thesmophoria was one of the most important annual events in the lives of ancient Greek women, granting them, like priestesses, the status of being able to take part in essential annual celebrations assuring fertility and abundance, vital rituals in the world of ancient Greece.