For most modern onlookers, the pyramids of Giza inspire humility and awe. These colossal structures are often viewed as timeless testaments to human ingenuity and the divine aspirations of the pharaohs. However, low-brow tales abound about how prostitutes built these awe-inspiring monuments.

These tales transform the reverential structures into props for an irreverent joke. Yet, these jovial stories reveal deeper insights into ancient attitudes towards authority and high-brow culture. They symbolize the enduring ability to “punch up” the self-absorbed ambitions of the ruling elite.

Rhodopis: From slave to courtesan and pyramid builder?

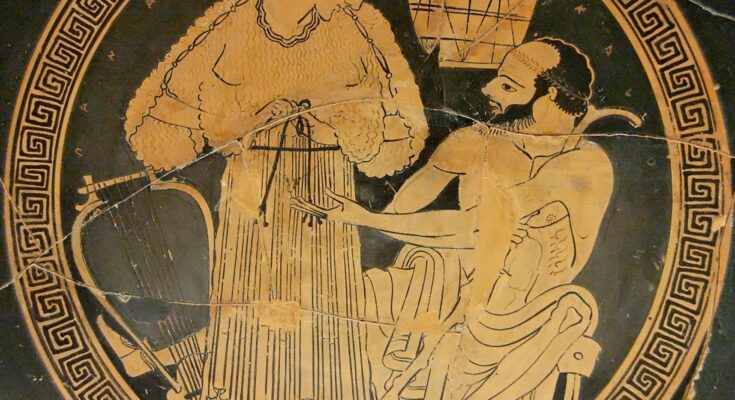

Rhodopis, a beautiful courtesan, has fascinated ancient storytellers for centuries. According to Herodotus, Rhodopis was a Thracian slave who found her way to Egypt. She gained her freedom and amassed considerable wealth through her wit and charm.

Her journey from servitude to affluence is remarkable. She was initially owned by a man from Samos named Iadmon, who also owned the storyteller Aesop. Rhodopis was brought to Egypt by another Samian named Xanthes. There, her fortunes changed dramatically due to the intervention of Charaxos, a wealthy merchant from Mytilene and brother of the poet Sappho.

Some Greek accounts even credit her with building the third and smallest pyramid at Giza, an assertion that adds to her mystique. Diodorus of Sicily adds a twist, suggesting that local governors, enamored with Rhodopis, commissioned the pyramid in her honor. This tale implies that her influence and beauty were so profound they could inspire grand gestures.

While Herodotus dismisses the idea that Rhodopis’ wealth was sufficient to finance such a grand project, the story persisted. It highlighted her famed beauty and allure and served as a playful critique of the grandiosity surrounding pyramid construction.

It is a former slave and not a god-incarnate who built the pyramids. What was Herodotus’ inspiration for such an outrageous idea? Like many of his stories, the historian’s inspiration may have been local jokes, like the Egyptian tale of Pharaoh Cheops’ daughter.

Cheops’ daughter: Do you take stones?

The story goes that Pharaoh Cheops’ pimped his daughter to finance his pyramid. Herodotus recounts the story as distinct from Rhodopis’ adventure. Facing financial difficulties, Cheops allegedly forced his daughter into prostitution.

This was supposedly for the purpose of funding the construction of the Great Pyramid. His daughter, displaying resourcefulness within her constrained circumstances, had a unique request for each customer: a single stone. She purportedly amassed enough stones to build her own small pyramid, situated before the Great Pyramid of Giza.

The joke goes even further, depicting her pyramid as a satirical monument to her father’s desperation and moral bankruptcy. As analyzed by PhD student Alex Tarbet, the story’s humor lies in its absurdity and subversion of royal dignity.

By turning a revered structure into a product of prostitution, the tale undermines the pharaoh’s grandeur. It suggests that even the most monumental achievements can have humbler origins.

Far from taking pride in their country’s most iconic monuments, some ancient Egyptians pilloried the famous pyramids. According to Tarbet, the general population despised these giant monuments to Cheops’ “hubris and selfishness,” built by the aching limbs of the impoverished peasants.

Egyptians who lived nearby hated the sight of the pyramids so much they refused to even utter Cheops’ name. Instead, locals referred to the pyramids using the name of a local shepherd, comparing the stone structures to sheep droppings that resemble small stones stacked together.

The locals’ jokes likely found their way onto Herodotus’ parchment. The Egyptians humorously reclaimed the pyramids as cultural sites belonging to the shepherds, women, and workers descended from their actual builders.

They depicted the local men who frequented the brothel as the true architects, turning the narrative on its head. This derisive display isn’t unique either.

Have you heard about the one with Setne?

A similar indignant tale is found in the Egyptian story of Setne, the favored son of Ramses the Great. Known for his self-given titles like “valiant heir” and “vigilant champion,” Setne’s tale involves a descent into a tomb in search of a magic book.

He attempts to seduce a priestess of the cat goddess Tabubu, only to wake up naked in the street with his genitals in a chamber pot full of excrement. This slanderous anecdote brought the pretentious Setne back down to earth, making him an object of ridicule.

Though clearly intended as jokes, these narratives reflect the ancient Egyptians’ capacity for humor and their disdain for the pharaohs’ monumental projects. By telling such stories, the people of ancient Egypt could subtly criticize their leaders and the immense resources diverted to these colossal tombs.

Far from viewing the pyramids as purely majestic, these stories allowed the common people to reclaim the pyramids. They mocked the rulers’ hubris and emphasized the labor and suffering of the masses who built them.

Pyramids financed by a prostitute

The stories of Rhodopis and Cheops’ daughter illustrate the complex interplay between myth and reality. At the same time, it illustrates the tensions between the working class and the elites.

While Herodotus, Diodorus, and other ancient historians provide varying accounts, they likely draw from jokes entertained by Egyptians themselves.

These low-brow anecdotes, far from diminishing the grandeur of the pyramids, enrich the understanding of the ancient world. They reveal deeper insights into ancient attitudes towards authority and high-brow culture.

Satire, then as now, was a powerful tool for social commentary and critique. By examining these stories, the present gains a more nuanced view of the unheard values, beliefs, and concerns of common people.