The Greek town of Santa, Dumanli in Turkish, situated in Pontus, has been a ghost town suffering neglect ever since the Greeks were forced to flee their ancestral homes in the exchange of populations with Turkey in 1923.

Santa, surrounded by tall mountains covered in fog year-round, is located in the province of Argyroupolis situated 52km southeast of Trabzon.

It’s believed Santa became established just after 1461 when Trebizond fell to the Ottoman Turks. Christians from surrounding regions of Trebizond such as Platana, Tonya and Muzena fled to the mountains to avoid Turkish persecution and harassment.

Before 1923 it was made up of 7 settlements; Pistofanton, Zournatzanton, Tsakalanton, Ischananton. Kozlaranton, Pinetanton and Terzanton and were inhabited entirely by Greeks, approximately 6,000 in number.

Around the end of the 19th century, Santa had 15 priests, 8 churches, 7 chapels, 5 schools, 9 teachers and some 260 students.

Administratively it belonged to the vilayet of Trebizond while ecclesiastically it originally belonged to the Diocese of Argyroupolis, then later to the Exarchate of Panagia Sumela, and lastly, it was transferred to the Diocese of Rhodopolis (Livera).

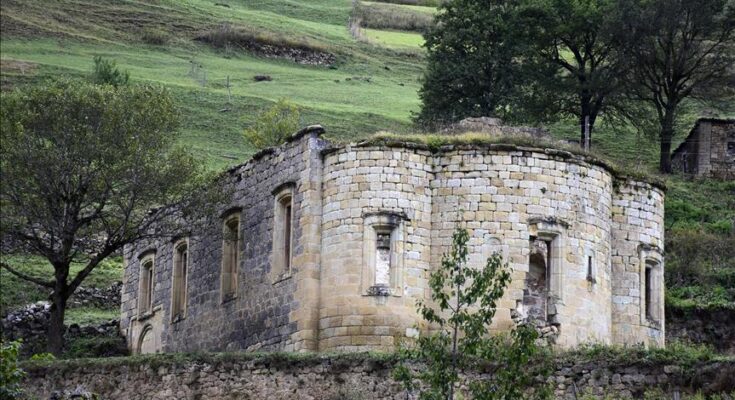

Santa in Pontus lies abandoned and neglected

Santa was once a bustling town with single-story houses, a church in each neighborhood, and a fountain on each street. Many jewelry stores and shopping centers could be found.

In 1923, when the Turkey-Greece Population Exchange agreement was signed, the Greeks migrated, and the remaining residents also left for economic reasons.

Since then, the ruins bear a deserted look.

“At the beginning of 1900s, especially after the Greeks migrated from our country as a result of the exchange, [the site] was left deserted,” Huseyin Ates, the province’s culture and tourism head told Anadolu Agency recently.

He added that after the 1950s, the Turk residents in the area also left due to various reasons.

“It is an area which has fallen into silence for 50 years and has been left to its fate,” he said.

After the population exchange, the Greeks who migrated to Greece called the homes they had left behind a “secret heaven”, said Ates.

Visitors can track traces of the Pontic Greek civilization in the area, he said, stressing the importance of the site in terms of nature and culture tourism.

He said he believed the Santa ruins would become an important tourist destination along the Green Road Project — a new road that will link the site to the Black Sea coastal road.

Ates has invited nature lovers and people interested in cultural heritage to visit the site.

“We will do everything to share this historical heritage with the next generations,” he told Anadolu.

The genocide of the Greeks of Pontus

The Greeks of Pontus suffered even before the population exchange of 1923. The Young Turk movement was started in 1908; the hard nationalist party was responsible for beginning the persecution of Christian communities and the forcible Turkification of the region.

Reacting to the oppression of the Turks — the murders, deportations and the burning of villages — Pontic Greeks took to the mountains to salvage what was possible of their culture.

After the genocide of the Armenians, the Turkish nationalists under Mustafa Kemal Ataturk then began the systematic extermination of the Pontic Greeks.

On May 19, 1919, Ataturk landed in Samsun to start the second and most brutal phase of the Pontian Genocide under the guidance of German and Soviet advisers.

By the time of the Asia Minor Catastrophe of 1922, the number of Pontians who died had exceeded 200,000; some historians put the figure as high as 350,000.