The Greek goddess Chimera, who was referenced in Hesiod’s seventh-century B.C. work “Theogony” and featured in Homer’s Iliad, was a monstrous composition of disparate parts that embodied an ancient fear of females.

Like so many other Greek goddesses, like Medusa, Lamia, Scylla, and Charybdis, she seemed to have been created out of mens’ fears regarding the power of females. She was a fearsome lion in front, a goat in the middle (which represented her ability to foster young), and became yet another terrible animal in the back, a dragon or snake.

She not only breathed fire, but was able to fly through the air and and ravage helpless towns. In particular, she seemed to have particular wrath for Lycia, an ancient maritime district in what is now southwest Turkey.

That is, until a male, the hero Bellerophon, managed to lodge a lead-tipped spear in her throat and choke her to death. Interestingly, in Greek mythology, it’s always a male figure that kills a female goddess or other figure that seemingly threatens men or the status quo.

Of all the fictional monsters of Greek mythology—and certainly all the female monsters— Chimera may have had the strongest roots in reality.

Her portrayal was the subject of a recent article by journalist and critic Jess Zimmerman, who argues in “Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology” that “women have been monsters, and monsters have been women, in centuries’ worth of stories because stories are a way to encode these expectations and pass them on.”

It is true that frightening female creatures feature in cultural traditions the world over, but Zimmerman focused on ancient Greek and Roman works of literature and art, which have had—by far—the most influence on American culture.

Several historians, including Pliny the Elder, argue that her origin is an example of a “euhemerism,” when ancient mythology might have corresponded to historical fact.

Indeed, the people of Lycia may have been so frightened by nearby geological activity at Mount Chimera, a geothermally active area where methane gas ignites and seeps through cracks in the rocks, that over time, the mountain, emitting angry flames, assumed the identity of a woman.

How women who historically are commonly classified as sweet and supposedly consistently even-tempered ever came to be associated with an feared volcano is beyond me. The small bursts of flames that came out of the mountain so spooked the local people that legends came to be created about them.

For ancient Greeks who came to tell stories about the monster, Chimera’s particular combination of fearsome and dangerous beasts and the domestic goat represented a hybrid, a contradictory horror that mirrored the way women were perceived as both symbols of domesticity and potential threats in much of Greek mythology.

Goat represents motherhood—and destructive ability

On the one hand, writes Zimmerman, Chimera’s goat body “carries all the burdens of the home, protects babies…and feeds them from her body.” On the other hand, her monstrous elements “roar and cry and breathe fire.”

She adds, “What (the goat) adds is not new strength, but another kind of fearsomeness: the fear of the irreducible, of the unpredictable.”

“To deviate in any way from the prescribed motherhood narrative is to be made a monster, a destroyer of children,” Zimmerman writes.

According to Hesiod, the Chimera’s mother was an unknown “she,” which may refer to Echidna. In this case, her father would presumably be Typhon, though possibly the Hydra or even Ceto was the one being referred to instead.

Homer gives a description of the Chimera in the Iliad, saying that “she was of divine stock, not of men, in the fore part a lion, in the hinder a serpent, and in the midst a goat, breathing forth in terrible wise the might of blazing fire.”

Both Hesiod and Apollodorus give similar descriptions: a three-headed creature, with a lion in front, a fire-breathing goat in the middle, and a serpent in the rear.

According to Homer, the Chimera, who was reared by Araisodarus (the father of Atymnius and Maris, the Trojan warriors killed by Nestor’s sons Antilochus and Trasymedes), was “a bane to many men.”

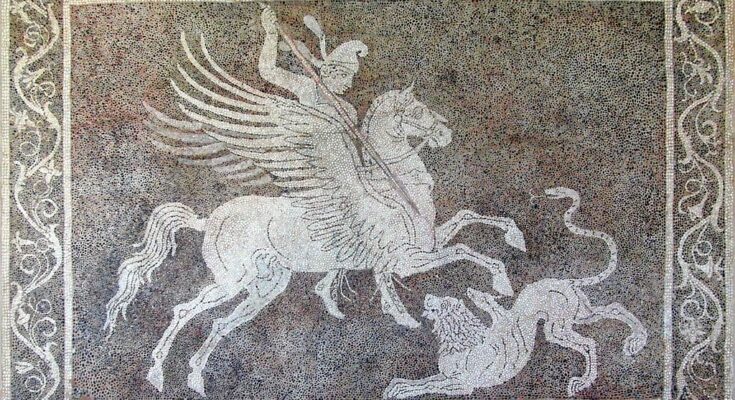

As related in the Iliad, the hero Bellerophon was ordered by the king of Lycia to slay the Chimera, but he was secretly hoping that the monster would instead kill Bellerophon. However, the hero, “trusting in the signs of the gods,” succeeded in killing Chimera. Hesiod adds that Bellerophon had help in killing the Chimera, saying “her did Pegasus and noble Bellerophon slay.”

A more complete account of the story is given by the historian Apollodorus of Athens. Iobates, the king of Lycia, had ordered Bellerophon to kill the Chimera (who had been killing cattle and had “devastated the country”). He thought that the Chimera would instead kill Bellerophon, “for it was more than a match for many, let alone one.”

But the hero mounted his winged horse, Pegasus, “and soaring on high shot down the Chimera from the height.”

Chimera—like all female monsters—killed by a man

As noted in Greek Reporter’s series of stories on fearful Greek goddesses and monsters, it is always, without exception, a male figure who kills these female creatures, and Chimera was no exception.

Artistic representations of this incredible beast first appear at an early stage in the proto-Corinthian pottery-painters, providing some of the very earliest identifiable mythological scenes that may be recognized in Greek art.

The Corinthian type is fixed, after some early hesitation in the 670s BC. The fascination with the monstrous devolved by the end of the seventh century into a decorative Chimera-motif in Corinth while the motif of Bellerophon on Pegasus took on a separate existence.

A separate Attic tradition came about in which the goat breathes fire and the animal’s rear is serpentine. Two vase painters employed the motif so consistently they were given the pseudonyms the Bellerophon Painter and the Chimaera Painter.

In Etruscan civilization, the Chimera appears in the Orientalizing period that even precedes Etruscan Archaic art. The Chimera appears in Etruscan wall-paintings of the fourth century BC.

Mount Chimera still contains some two dozen vents in the ground, which are grouped in two patches on the hillside above the site of the Temple of Hephaestus, approximately three kilometers (five miles) north of Çıralı near ancient Olympos in Lycia.

The vents to this day emit burning methane, which is thought to be of metamorphic origin. The fires that are emitted from the vents were landmarks in ancient times and were even used for navigation by sailors.

A neo-Hittite Chimera, appearing on a stone relief from Carchemish, dated back to 850 to 750 BC, which is now housed in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, is believed to be a basis for the Greek legend.

It differs, however, from the Greek version in that a winged body of a lioness also has a human head rising from her shoulders.

The term “chimera” has come to describe any mythical or fictional creature with parts taken from various animals, to describe anything composed of very disparate parts, or perceived as wildly imaginative, implausible, or dazzling.

Chimera’s legend proved so influential that it even seeped into modern scientific parlance. In the scientific world, “chimera” now refers to any creature with two sets of DNA.