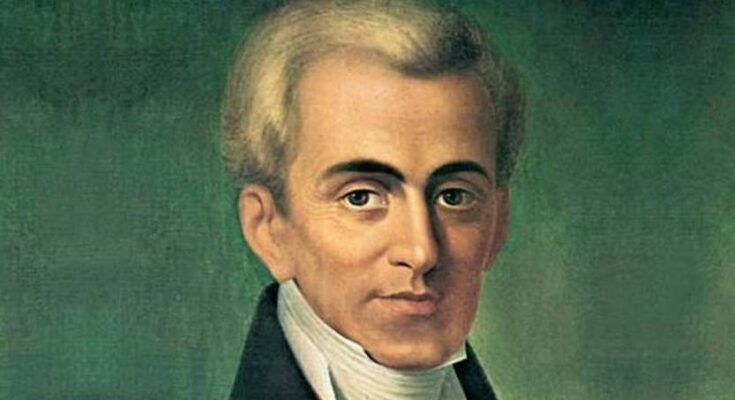

On September 27, 1831, Ioannis Kapodistrias, the first leader of Greece after the Ottoman occupation, was assassinated in Nafplio. His murder robbed the country from the chance to become a modern state sooner.

Kapodistrias was born on Corfu on February 11, 1776 when the island was under Venetian rule. Coming from a noble family, Kapodistrias studied philosophy and law and became a sought-after diplomat who later became Minister of Foreign Affairs of Russia (1816-1822).

When he became the first governor of the independent Greek state, he established it from scratch and used his personal wealth to fund this endeavor.

In 1822, he settled in Geneva, Switzerland, where he contributed to the creation of the Swiss Federation, receiving the title of honorary citizen. He remained there until 1827, simultaneously helping the Greek Revolution.

On March 30, 1827, the National Assembly of Trizina elected him Governor of the newly established Greek state. After arduous consultations in European capitals to ensure the necessary support for the Greek state, he arrived in Nafplio on January 7, 1828 and was welcomed with enthusiasm and celebrations.

His first period as a governor was daunting, as the rivalry that arose between the factions during the revolution had not abated. Furthermore, the country was bankrupt.

Kapodistrias asked to lead the new Greek state

Kapodistrias was asked to rule on the basis of the Republican Constitution of Trizina, but, as a believer in enlightened despotism, he thought that a constitution and parliamentary bodies were too premature for a state that was not yet built.

On January 18, 1828, he managed to convince parliament to suspend the Constitution. Hence, he achieved absolute power, aided by the Panellinion, an advisory body consisting of twenty-seven members.

Greece’s first leader set out to put an end to civil conflicts and served immediately for the purpose of creating a state from scratch.

He founded the National Bank with the help of a Swiss friend who was a banker and adjusted the monetary system, as foreign and Turkish currencies were still circulating in Greece.

On July 28, 1828, Kapodistrias established the Phoenix as the national currency and founded the National Mint. On September 24th of that year, he established the first postal service.

Knowing that the administration of justice is the foundation for the creation of a well-governed state, he took personal interest in the establishment of courts staffed with the appropriate personnel.

He organized the state administration and founded the Statistical Service, which conducted the first census.

Kapodistrias reorganized the armed forces under a single command, managing at the same time to fight the establishment of chieftains and to prevent the Ottoman advance, as shown in the Battle of Petra.

The Greek army appeared disciplined and structured in the last battle of the Greek War of Independence. The new navy eliminated piracy in Greek waters.

Kapodistrias applied quarantine procedures in communities that were affected by epidemics of typhus, malaria, and other contagious diseases. He attempted to rebuild the damaged educational system of Greece, founding many schools and the Orphanage of Aegina.

Kapodistrias introduces Greeks to the potato

The first governor took decisive steps in boosting agriculture, seeing it as the cornerstone of the Greek economy. He introduced the cultivation of potatoes in a way that showed his deep knowledge of the psyche of the Greeks of that era.

Kapodistrias ordered that a load of potatoes be brought to the Nafplio harbor and urged everyone to get as many as they wanted. Greeks viewed the new vegetable with icy indifference. Consequently, he placed guards around the potato shipment, and Nafplio residents began circulating the rumor that the army was guarding valuable cargo at the port.

People gathered at the port and began slowly stealing the potatoes from under the noses of the guards until all potatoes were gone. They didn’t know, however, that Kapodistrias had instructed the guards to turn a blind eye. With this clever move, the potato became part of the daily diet of Greeks.

Kapodistrias’ policies, though, caused resentment, both of the constitutional regime supporters, and the elders and sailors. The glory that surrounded him began to dissolve. Failure to satisfy all, combined with the delay of the elections, created a strong opposition against the Governor.

Kapodistrias was even accused of ignoring Greek traditions and wanting to import foreign institutions and mores.

The first rebellious move came from Hydra in 1829, when the navy sought to overthrow the government. Kapodistrias managed to suppress the coup with the help of the Russian navy. Yet, discontent was rising.

The assassination of the first leader of Modern Greece

The big farmland owners of Mani—led by the Mavromichalis family—refused to pay taxes to the central government and revolted.

The rivalry between Kapodistrias and the Mavromichalis family escalated and proved to be fatal in the end. The governor ordered the arrest and imprisonment of elder Petrobey Mavromichalis.

Petrobey’s brother, Constantinos, and his son, Georgios, decided to seek revenge. On the morning of September 27, 1831, they slaughtered Kapodistrias outside the church of St. Spyridon where he was planning to attend mass. The governor was accompanied only by his one-armed bodyguard.

Constantinos Mavromichalis was lynched on the spot by Nafplio residents. Georgios Mavromichalis took shelter in the French Embassy, where he sought asylum. The angry mob threatened to burn down the embassy, forcing the French to release him.

Mavromichalis was tried and sentenced to death by court martial and was executed by firing squad on the morning of October 10, 1831.

After Kapodistrias’ murder, Greece plunged into chaos. Anarchy prevailed, and, a few months later, England, France, and Russia convened in London. On May 8, 1832, it was decided that the seventeen-year-old German Prince Otto would be appointed King of Greece.

On February 6, 1833, Otto arrived in Nafplio and had a welcome similar to that of Kapodistrias.

Swiss philhellene I.G. Eynard wrote at the time: “He who murdered Kapodistrias, murdered his homeland. His death is a disaster for Greece and a misfortune for Europe.”

For many historians, Kapodistrias would have been the man to make Greece a modern state much sooner, the way he had helped build Switzerland. It is doubtful that Greece would have followed the same course with a foreign king, as the one appointed by the super powers of the time.

If Kapodistrias had lived and was allowed to materialize his vision, Greece would have been a totally different country today.