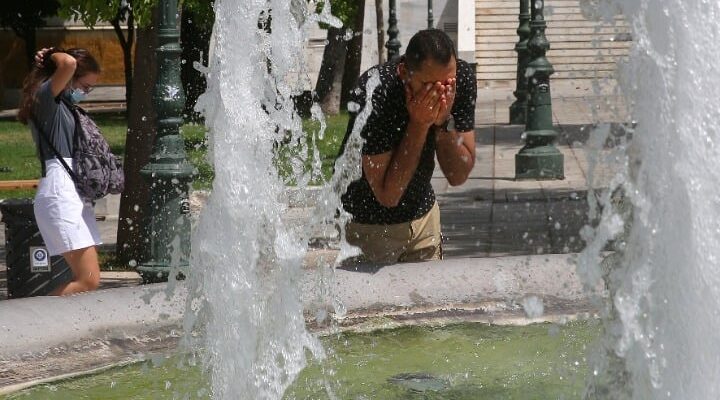

As Greece currently faces yet another heatwave, this brings to mind the deadly scorching days of July 1987 when more than 1,300 people lost their lives to the heat.

Like almost every summer since, heatwaves are hitting the country. These are now more frequent, and temperatures are higher. This week, Greece is bracing for the third heatwave this summer which, according to meteorologists, may last up to 15 days.

As intense as the coming heatwave may be, Greece is now well prepared to face extreme temperatures, unlike the six days of July 1987. In those days, temperatures climbed to 44 degrees Celsius (111.2 Fahrenheit) and the country mourned more than 1,300 people. Urban centers faced warlike conditions in hospitals and morgues.

The 1987 ‘killer’ heatwave

It was July 22, 1987 when the thermometer began peaking alarmingly. The Greek newspaper Ta Nea reported at the time that the entire country was “boiling like a vast furnace” and that unusually high temperatures would continue to afflict residents of major cities until that Sunday, according to the National Meteorological Service.

The newspaper added:

“Yesterday’s heatwave contributed to the death of four people (two in Athens and two in Volos) who suffered from heart disease, while dozens of others—mostly elderly—were transferred to various hospitals with cardiorespiratory problems.”

However, that was only the beginning of the six-day long heatwave. The situation got out of control quite quickly. By July 25th, the death count had reached 300 and was rising. Hospitals across Greece began reporting dozens of deaths and asking for help, as there were no vacant beds for incoming patients. Meanwhile, the dead were multiplying at such a rate that there was no room in the hospital morgues for the bodies. Authorities were forced to use military hospital morgues to place the dead.

The extreme heat in Athens in particular was due to miles of hot asphalt compounded by countless cars emitting leaded gasoline pollution. Tall cement buildings and apartment blocks made temperatures even more unbearable. In fact, the metropolitan train for the Omonoia Square – Piraeus route stopped operating because the rails were overheated and consequently expanded.

By July 26th, headlines like “Athens, dead city,” (To Vima) appeared in most newspapers. It was reported that this had been the deadliest heatwave in Greece in recent times. A day later, Ta Nea added a reluctant tone of optimism: “Athens is still a dead city today. And the residents who have survived can hope that, from tomorrow afternoon, the heat—the deadliest in recent years in Greece, as it seems—will subside.”

Most people locked themselves in their homes unable to go out and face the sweltering heat. Schools and public services were closed for safety reasons.

On July 28th, temperatures started to cool down. It was the end of a nightmare for Greece. It was also a time to realize the hazardous consequences of pollutant emissions and the tons of concrete that make up the infrastructure of large cities.

Lack of proper infrastructure

The two main reasons that Greece was unable to deal with the 1987 heatwave was the lack of infrastructure for dealing with such extreme weather phenomena. The second was the element of surprise.

At the time, words like “climate change” or “global warming” had not appeared in the international vocabulary yet. In Greece, summers had always been warm but not extremely hot. The days were quite warm while nights were cool. The occasional heatwaves were manageable, and temperatures above 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 Fahrenheit) were rare.

Given the Greek climate up until the 1980s, air conditioning in homes was also uncommon. Air conditioners were installed only in hospitals and some hotels. Furthermore, the economic prosperity from the 1980s and on had shot car sales to the roof. Yet most cars did not have catalytic converters, and the emissions had created a cloud of pollution over Athens.

As Athens is surrounded by the Parnitha, Hymettos, and Penteli mountain ranges that create a basin (the Attica basin), the cloud of pollution looms over Attica until strong winds blow it away.

If one also considers the masses of cement that comprise most of Athens, the 1987 heatwave was a catastrophe and a wake-up call at the same time. Public agencies, ministries, schools, restaurants, bars, cafes, and residences began getting equipped with air conditioning units. By the 1990s, all cars had catalytic converters, and the cloud of pollution over Attica disappeared.

Today, Athens and the rest of Greece are protected when heatwaves hit. Even though average summer temperatures are higher than those of 1987, almost all buildings and homes are air-conditioned. Moreover, the Civil Protection agency sends warnings via text messages during extreme weather phenomena. Greek citizens are generally much more aware of the hazards of climate change and are better prepared to protect themselves.