The Aztec Empire was one of the most dominant forces the world had ever seen, but it would fall from grace in a span of two and a half years.

In 1519, the Aztecs ruled an empire that covered 800,000 square miles of land and was home to 6 million people. Its capital, Tenochtitlan, was a marvel of civil engineering and was home to 300,000 people, making it one of the three largest cities in the world at the time.

Emperor Moctezuma II, known as a wise and cunning leader, ruled the Aztecs during this period. With such a large and successful empire, millions of people, thousands of soldiers, and an intelligent ruler, it’s a wonder that by 1521, the Aztec Empire would collapse in ruins.

How did this once great empire have such a rapid demise? The world has Hernán Cortés and his crew of 500 mutineers to thank for that.

The ambitions of Hernán Cortés

Spain was building its empire in the 15th and 16th centuries, conquering and colonizing places like Cuba, Haiti, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico.

Rumors were floating around the colonies that there was a land mass to the west where the natives had tons of gold. After expeditions funded by Diego Velázquez, the governor of Cuba, the Spanish found that it wasn’t just a land mass but an entire continent.

Knowing the natives possessed vast riches, Velázquez hired his brother-in-law Hernán Cortés to explore the land. While Cortés was the ideal candidate, he was too ambitious, and the people around Velázquez knew it.

Velázquez’s advisors warned him and convinced him to take Cortés off the expedition. However, Cortés caught wind of the plot and set sail before word could officially reach him, turning him and his crew into mutineers.

Cortés knew that when he returned to Spain, he would likely be tried for crimes and imprisoned. But he figured the Spanish crown would forgive him if he brought back a mountain of gold and silver.

The Aztec Empire’s iron fist

The Aztecs came into being when three of the most powerful city-states around Lake Texcoco, Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan, united to control what is now central Mexico.

The Aztec Empire was unconventional in its conquests. When they conquered a place, they changed absolutely nothing about it. They didn’t even bother to rule over their new acquisition. Instead, they demanded that the newly conquered place pay tribute. The people and its leaders would be safe if they paid the tribute. They would send elite soldiers over to injure or kill if they didn’t pay it until they received their tribute.

This system worked exceptionally well, but the only side effect was that their subjects detested them.

Cortés acquires the key to conquest

Hernán Cortés and the mutineers first stopped at Cozumel, where they already had good relations with the Mayans. They made a pit stop to stock up on munitions and supplies.

During their stop, they heard a rumor about two white men living on the mainland. Cortés investigated the claims for himself. He found the men, who were both Spanish and had lived on the mainland for eight years after being shipwrecked.

The two men integrated themselves in the local community and learned the ways of the Mayan people, including their language. Recognizing the potential benefit of their expertise, Cortés invited them to join his expedition.

One of them had a family, so he refused. The other one, Friar Gerónimo de Aguilar, agreed to join Cortés.

With de Aguilar on his crew, they set sail to the Mayan mainland city of Potonchán. Since these Mayans didn’t know them, they had to fight them. They won the battle, and the town leader gave them food, gold, and 20 slaves.

One of the slaves had an affinity for languages, and seeing her value, Cortés named her Marina and made her an essential crew member. Marina, also known as “La Malinche,” spoke fluent Spanish and Yucatec Mayan, but her native tongue was Nahuatl, the Aztec language.

Cortés developed a system with his two translators. He would speak in Spanish to de Aguilar, who would then translate it to Yucatec Mayan for Marina, and Marina translated that to Nahuatl.

With the combination of de Aguilar and Marina, Cortés unknowingly got himself the key to toppling the Aztec Empire.

The rogue expedition arrives in the Aztec Empire

Cortés and his crew reached the Aztec Empire but were surprised to be greeted with a welcome party.

Moctezuma knew of the Spaniards’ arrival on the mainland before they set foot in the Aztec Empire. Moctezuma didn’t fear Cortés or his crew but was wary of the flag they represented. The risk of making an unknown enemy like Spain was risky, so instead of greeting Cortés with violence, he greeted him with gifts of gold and riches.

Moctezuma hoped to make an ally of the Spanish by giving them gifts, but his benevolence had the opposite effect. Moctezuma’s gifts alerted Cortés to the sheer amount of gold and silver the land possessed, and he wanted it all.

Cortés first created a settlement named “La Villa Rica de la Veracruz.” Today, this city is known as Veracruz. Then, he allied with the neighboring city of Cempoala and convinced them to go against their Aztec rulers. He sowed chaos, but it was quickly thwarted by Moctezuma, who gave out more gifts to quiet everyone.

The crew made their way to Tlaxcala, a nation in the middle of the Aztec Empire, but not a part of it. They were met with hostility, but during the fight Cortés captured soldiers, told them through de Aguilar and Marina that they came in peace and were enemies of the Aztecs, and released them back to their people to relay the message.

The plan stopped the conflict, and they were invited to the Tlaxcalan capital, Tlaxcala. Cortés spoke with the leaders of Tlaxcala over the next three weeks. He learned they had been engaged in a generational war with the Aztecs, known as the Flower War.

In those three weeks, he converted several Tlaxcalan nobles to Catholicism, married off some of his lieutenants to Tlaxcalan princesses, and established an alliance with the nation of Tlaxcala.

The Cholula Massacre

The crew left Tlaxcala and went to the Aztec city of Cholula. Having known of their time in Tlaxcala and Cholula’s proximity to the capital, Moctezuma did not respond kindly to their arrival.

He ordered the local Cholula chiefs to murder Cortés and his crew in the dead of night. Marina heard of the plot while in town from the wife of a noble, and she notified Cortés immediately.

Cortés responded by causing a bloodbath of the city and torching it. Supposedly, Cortés and his men murdered 3,000 people in just three hours. This would be known as the Cholula massacre.

Capturing Moctezuma

Moctezuma heard of the massacre, and Cortés and his crew marched over to Tenochtitlan.

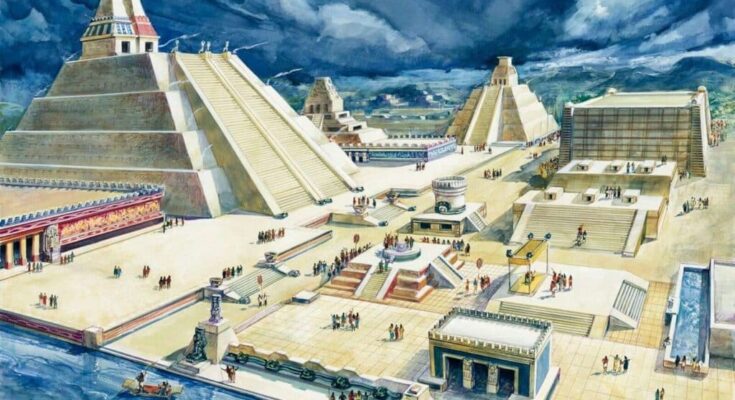

Tenochtitlan was an island city situated in Lake Texcoco. The Aztecs built manmade causeways and bridges to connect the city to land, so the only way to enter was by boat or through the causeways.

If Cortés and his men ever looked down on the Aztecs, their views were changed when they set foot in Tenochtitlan. Thanks to the Aztecs’ superior civil engineering, the city was arguably one of the most advanced in the world. They had two massive aqueducts to bring water into the city and an ingenious canal system for transport and irrigation.

Tenochtitlan was home to 300,000 people, compared to London’s population of 50,000 at the time. The Aztecs built artificial islands around the main island to accommodate more people.

Moctezuma chose to greet the Spanish in his finest gold garments on one of the bridges, and he welcomed the crew into the city with magnificent gifts.

No one knows how it happened, but that night, Cortés captured Emperor Moctezuma II and placed him on house arrest. Moctezuma was allowed to go about his duties in his home, but from that time on he was no more than a puppet for Cortés.

Velázquez retaliates

Meanwhile, Diego Velázquez assembled a crew led by conquistador Pánfilo de Narváez. Narváez’s crew was twice the size of Cortés’ and possessed horses and more munitions.

Narváez’s crew attacked Cempoala, and Cortés went there with 200 of his best men and 200 Aztecs to reclaim the city.

Cortés was outnumbered two-to-one but had the advantage of being familiar with the land and its people, so he orchestrated a sneak attack in the middle of the night. He killed Narváez’s horses and blew up the gunpowder first before attacking.

The attack was a rousing success. Upon hearing of the Aztecs’ riches, Narváez’s remaining crew defected and joined Cortés. From this battle, he won hundreds of men and plenty of horses.

The massacre in the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan

The problem with taking his best men to Cempoala was that Cortés left behind his worst men in Tenochtitlan.

While Cortés was gone, the Aztecs held the Feast of Toxcatl in the great temple of Tenochtitlan. The Aztecs, of course, dressed in their finest gold garments for the occasion.

Cortés left Pedro de Alvarado in charge, a good conquistador but ill-suited to leadership. No one knows whether de Alvarado heard of a plot against the Spanish or if he was sent into a bloodthirsty rage upon seeing so much gold, but either way, by the time Cortés arrived, the city was up in flames, and the Aztecs and Spanish were fighting.

Cortés immediately sprung into action and ordered Moctezuma to tell the Aztecs from atop a roof to allow the Spanish safe passage out of the city. The Aztecs already knew he was compromised and paid him no heed.

Moctezuma was stoned to death on that roof by either Aztecs or Spanish; no one truly knows. After this, Cortés and his most trusted lieutenants escaped on horseback to Tlaxcala, but the others in his crew weren’t so lucky. Tenochtitlan was nearly impossible to escape, and many Spaniards drowned or were murdered that night.

This night is known as the massacre in the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan. 800 Spanish and 4000 natives died in the massacre.

Disease and the fall of the Aztec Empire

Upon leaving the city, the Spanish left a surprise behind them. Narváez’s crew was carrying smallpox, and they transferred it to Cortés’ men, who gave it to the Aztecs.

While people in Europe and Asia had dealt with the disease for millennia and built up a minor immunity to it, the North American continent had never seen the disease.

As a result, nearly 50 percent of the population was wiped out in just three months, including the new emperor of the Aztecs.

After six months of strengthening his crew and recovering in Tlaxcala, Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan. He conquered the cities surrounding the lake and laid siege to the great city. He surrounded it with boats, destroyed the aqueducts, and blocked off the bridges and causeways, trapping the Aztecs.

He laid siege for eight months before Tenochtitlan fell and the sitting Emperor Cuahtémoc was captured after he tried to flee in a canoe.

The city was in ruins, and by August 13, 1521, the Aztec Empire was gone.

The aftermath

The city was in ruins after being torched and sieged. The people were brutalized. Cortés needed to rebuild, and he did.

The Spanish drained the lake and created a massive city, which Cortés named Mexico City. The city still suffers from being on a lakebed, and earthquakes are frequent. While he made the city and founded New Spain, the Spanish appointed Antonio de Mendoza as the governor of New Spain, unable to trust Cortés after his antics.

Cortés spent the rest of his life between Old and New Spain, where he was a trusted and prominent aide to the Spanish crown. New Spain eventually spanned 5 million square miles.

Smallpox, along with measles and influenza, would ravage the native population. The population was 30 million by the time Cortés’ arrival, dropping to 3 million when New Spain was established.