The infernal rivers of Greek mythology, ruled by Hades, the god of the dead and king of the underworld, are often mentioned in ancient literature.

Roman poet Virgil gives a complete account of the five rivers of Hades in his Aeneid although some of his information differs from older sources, such as that of Homer and Plato.

The five rivers—Acheron, Styx, Phlegethon, Cocytus, and Lethe—each had their own distinct function in the religion and mythology of the Greek underworld along with a unique character to symbolize the respective emotion or god associated with death.

River Acheron, entrance to the Greek underworld

Acheron, a large river located in the Epirus region of northwest Greece, features most prominently in Greek mythology as the greatest among the five rivers of Hades.

In ancient Greek literature, Acheron was portrayed as the entrance to the underworld and is mentioned both as a river and a lake.

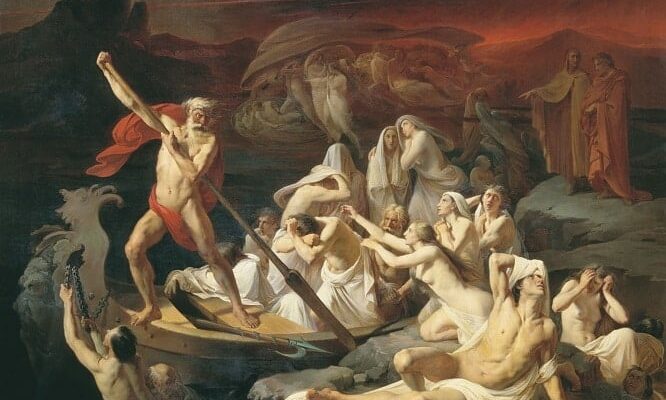

According to mythology, Hades’ ferryman and psychopomp, the dark and fearsome Charon, transported the dead from the banks of Acheron to the “other side” in exchange for a low-value coin that the dead should have been buried with.

Indeed, archaeological finds confirm the custom that ancient Greeks buried their dead with a coin under their tongue or beside the vessel that contained their ashes.

Ancient sources as old as Homer (8th century BC) describe the Nekromanteion on the banks of Acheron, a temple of necromancy devoted to Hades and Persephone, where participants went through cleansing ceremonies as they sought to speak to the dead.

An archaeological site discovered in Epirus in 1958 was identified as the Nekromanteion, but this was later disputed by scholars, as its geography, dating, and excavation findings don’t seem to match the hypothesis.

Strangely enough, Acheron Lake in Antarctica is named after this Greek mythical topography of the underworld.

The deadly River Styx

The River Styx was the most dreadful among the Rivers of Hades, as the extraordinary qualities of its waters were feared even by the gods.

According to Herodotus, the river originated near Corinth while Hesiod refers to the Arcadian Styx in the Peloponnese as well.

The deities of the Greek Dodekatheon swore all their oaths upon the River Styx because, according to Greek mythology, during the Titanomachy, Styx, the goddess of the river, sided with Zeus.

The river’s waters would destroy anyone and anything that would fall into them, but it was in these same waters that the nymph Thetis dipped her son Achilles to make him invulnerable.

In his Theogony, Hesiod says that when two gods were in dispute, they would take an oath in front of a golden amphora filled with water from the Styx in the presence of Zeus. The one who was wrong would instantly be paralyzed, become mortal for one year, and be excluded from the gods’ councils for another nine years.

According to Roman poet Virgil, the River Styx sprang from Acheron, which was the principal river of Tartarus, the dark abyss. In his own account of the Greek underworld, which was followed by many later writers, the cross over to “the other side” is described as taking place at the River Styx instead of Acheron.

The dead who could not pay the cross-over fee to Charon, and those who had received no funeral rites, had to wander near the shores of the Styx for one hundred years before they were allowed to cross the river and enter the underworld, as per Virgil.

Punishment for murderers in Phlegethon and Cocytus

Phlegethon, the River of Fire, ran parallel to Cocytus, the River of Wailing. The two rivers merged in a loud waterfall that fell into Acheron, according to Homeric poems.

Plato describes Phlegethon as “a stream of fire, which coils round the earth and flows into the depths of Tartarus” while the soil on its banks turns to burning clay where it meets the waters.

Any dead who had committed matricide or patricide when alive were thrown into Phlegethon while anyone who had committed any other type of homicide in hot blood and regretted their actions later was thrown into Cocytus.

They all kept moving between Tartarus and Acheron Lake via the two rivers until they were granted forgiveness from their victims to whom they pleaded with cries and loud screaming.

Still, they were luckier than cold-blooded and unrepented murderers, who would immediately end up in the Tartarus.

The myth of Phlegethon inspired both Dante in his “Inferno” and Edgar Allan Poe in his Descent into the Maelstrom.

Lethe, the Greek underworld’s river of oblivion

The River Lethe takes its name from the ancient Greek word for oblivion and forgetfulness.

Ancient Greeks believed that souls were made to drink from this river to have their memories erased before being reincarnated so that they would not remember their past lives.

However, an Orphic inscription on an ancient pendant excavated in Southern Italy and showcased at the British Museum, advises the wearer not to drink from the River Lethe but rather seek the waters of Mnemosyne, the Pool of Memory.

The River Lethe does not identify with a specific river in modern-day Greece.

However, Pausanias and Plutarch make mention of two springs named Lethe and Mnemosyne at the oracular shrine of the local hero and god Trophonius in Boeotia in Central Greece. Worshippers would drink from these prior to consulting with the god.

The oracle of Trophonius, which was described as an underground shrine, has not yet been discovered.

It could be, perhaps, that the River Lethe defeated Mnemosyne and they both drifted away into oblivion.