Determining the exact “oldest” languages can be challenging as the origin of many ancient languages is often shrouded in mystery. However, based on historical evidence and linguistic research, historians and philologists can make educated guesses.

Ancient written languages emerged as a revolutionary development in human history, allowing civilizations to record and preserve their knowledge, culture, and history for future generations.

The study of ancient languages, known as philology or historical linguistics, is vital for deciphering ancient texts, understanding cultural interactions, and tracing the migratory patterns of early human populations. Comparative linguistic analysis allows researchers to identify language families and reconstruct proto-languages, which can provide insights into prehistoric societies and their ways of life.

The oldest languages and the importance of writing

According to the British Library, the invention of full writing systems seems to have occurred independently in at least four distinct instances. The earliest of these occurred in Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) around 3400 to 3300 BC, where the script known as cuneiform was employed. Shortly thereafter, around 3200 BC, a writing system emerged in Egypt. By 1300 BC, during the late Shang dynasty in China, there is evidence of a fully functional writing system in use. Sometime between 900 and 600 BC, writing also made its appearance in the cultures of Mesoamerica. In addition to these known instances, there are certain regions like the Indus River Valley but the scripts remain undeciphered.

Although the dates of these developments suggest the possibility of writing spreading from a central point of origin, there is limited evidence of direct links between these writing systems. Each system possesses unique characteristics, indicating independent invention in various parts of the world.

The diversity of these ancient scripts reflects the ingenuity and creativity of different human cultures, each finding its distinctive way to express and record information. The study of these ancient writing systems not only sheds light on the history of human communication but also enhances our understanding of the cultural and intellectual achievements of our ancestors.

Mesopotamia

According to scholarly consensus, writing’s earliest form emerged approximately 5,500 years ago in Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq. Initially, it comprised simple pictorial signs, which over time evolved into a more intricate system of characters that represented the sounds of Sumerian and other languages spoken in Southern Mesopotamia.

Around 2900 BC, these characters were impressed onto wet clay using a reed stylus, creating wedge-shaped marks now known as cuneiform. This innovative writing method marked a significant advancement in recording and preserving information, playing a crucial role in the development of ancient civilizations and the dissemination of knowledge.

Over the next 600 years, the process of writing cuneiform became more standardized. Curves were removed, signs were simplified, and the connection between pictograms and their original objects was lost.

During this period, the symbols, initially read from top to bottom, shifted to be read from left to right in horizontal lines, though vertical alignments were retained for traditional pronouncements. The symbols were also realigned and rotated 90 degrees anti-clockwise.

Around 2340 BC, Sumer fell to the Akkadian armies led by King Sargon. Cuneiform had been used bilingually for Akkadian alongside Sumerian for centuries. The Akkadians built a vast empire, spanning from present-day Lebanon to the Persian Gulf, and cuneiform-inspired characters were adopted by as many as 15 languages.

Sumerian remained the language of learning until at least 200 BC, but cuneiform as a writing system outlived it by almost three centuries, continuing to be used for other languages well into the Christian era. The last known datable cuneiform document is an astronomical text from 75 AD.

Egypt

Recent archaeological discoveries have shed new light on the ancient Egyptian written language, revealing an earlier date for its origins, closely resembling that of Mesopotamia. The rock art site of El-Khawy in Egypt, dating back to around 3250 BC, has unveiled large-scale incised ceremonial scenes that bear striking similarities to early hieroglyphic forms. Some of these rock-carved signs are nearly half a meter tall, demonstrating the significance of writing in ancient Egyptian culture.

Around 3200 BC, Egyptian hieroglyphs appeared on small ivory tablets used as labels for grave goods in the tomb of the pre-dynastic King Scorpion at Abydos. They were also found on ceremonial surfaces employed for grinding cosmetics, like the Narmer Palette.

It is worth noting that Egypt can be credited with the invention of ink writing using reed brushes and pens, a significant development. The Greek term “hieratic” (meaning “priestly” script) referred to this ink writing, while the carved and painted letters seen on monuments were termed “hieroglyphs” (meaning ‘sacred carvings’).

The discovery of closely dated carved and written characters implies that Egyptian writing served two distinct functions from its earliest times. One was ceremonial, serving as a display script through carvings, while the other served the practical needs of royal and temple administrations through written forms.

Within a span of four centuries from the findings in King Scorpion’s tomb, hieroglyphs and Hieratic (the cursive writing system for Ancient Egyptian) underwent substantial development, encompassing 24 uni-consonantal symbols, phonetic components representing combinations of sounds, and determinative signs that had no phonetic value but helped discern the intended meaning of a word in a given context.

From this sophisticated Egyptian writing system, the concept of an alphabet gradually evolved, with its roots dating back to around 1850 BC. The enduring legacy of ancient Egyptian writing significantly impacted the history of human communication, leaving a lasting mark on the development of writing systems across various civilizations.

China

The earliest traces of writing in China were discovered near present-day Anyang, close to the Yellow River’s tributary, about 500km south of Beijing. These inscriptions were found on the “oracle bones“, the shoulder blades of oxen, and turtle plastrons, used by the late Shang dynasty kings (1300–1050 BC) for divination rituals.

For centuries, these bones, known as “dragon bones,” had been collected by farmers for use in Chinese medicine until politician and scholar Wang Yirong recognized the characters carved on them in 1899. The discovery of these inscriptions expanded Chinese historical and linguistic knowledge by several centuries, as they became the earliest written records of Chinese civilization.

The ‘oracle’ bones contain over 4,500 different symbols, many of which are ancestors of the Chinese characters still used today. However, deciphering the Shang script is challenging, and many characters remain undeciphered. The characters that can be identified have also evolved significantly in form and function over time. Early pictographic characters became more abstract, and new compound forms emerged as the written vocabulary expanded.

Chinese characters have had the unique ability to represent both concepts and sounds of spoken language since ancient times. Basic components were shared between characters to indicate similarities in pronunciation or meaning.

These ‘oracle’ bones provide evidence of a fully developed writing system, likely formed many years, if not centuries, before their discovery. Although earlier materials may not have survived, the significance of the ‘oracle’ bones underscores the ancient origins of the Chinese written language and its enduring impact on human communication.

Mesoamerica

Recent discoveries in Mesoamerica, spanning from southern Mexico to Costa Rica, have pushed the evidence for writing in the region back to around 900 BC. These findings have expanded our knowledge of cultures and languages that utilized writing, including not only the Maya, Mixtecs, and Aztecs but also the earlier Olmecs and Zapotecs.

In pre-colonial Mesoamerica, two types of writing systems existed:

Open systems were utilized as means of recording texts without being tied to specific language structures. They served as mnemonic devices, guiding readers through narratives regardless of their linguistic background. Such systems were prevalent among the Aztecs and other Mexica communities in central Mexico.

Closed systems were intricately connected to the sound and grammatical structures of particular languages. These targeted specific linguistic communities and functioned similarly to modern writing systems. The Maya, for instance, used closed systems in their writing.

The role of a scribe held high status in Mesoamerican society. Maya artists, often younger sons of royalty, were entrusted with this important position. The Keepers of the Holy Books, the most esteemed scribal office, assumed multiple roles, serving as librarians, historians, genealogists, tribute recorders, marriage arrangers, masters of ceremonies, and astronomers.

From the pre-colonial era, only four Maya books and fewer than 20 from the entire Mesoamerican region have survived. These codices were painted onto deer skin and tree bark, with the writing surface coated with a polished lime paste or gesso, much like many of the buildings from that time. These precious surviving manuscripts provide valuable insights into the ancient cultures and writing practices of Mesoamerica.

Indus Valley

In the Indus River valley of Pakistan and northwest India, archaeologists have discovered symbols on various objects that are believed to be a form of writing. This ancient civilization, which thrived from at least 7000 BC, reached its pinnacle between 2600 and 1900 BC when a sophisticated urban culture flourished in the region. However, after 1900 BC, the once-thriving cities declined.

While approximately 5,000 inscribed artifacts have been found, the majority of the inscriptions consist of just three or four symbols. The longest inscription discovered contains 26 symbols.

The Indus River Valley script comprises around 400 unique symbols, a relatively small number compared to what would be expected for a fully developed logographic word-based writing system. Instead, scholars have proposed that similar to pre-dynastic Egyptian hieroglyphs and early Sumerian script, the Indus script may be a combination of logographic and syllabic components. This suggests that the symbols could represent both individual words and syllabic elements, adding to the complexity of deciphering this ancient script and unraveling the secrets of the Indus Valley civilization.

Where does Greek fit in?

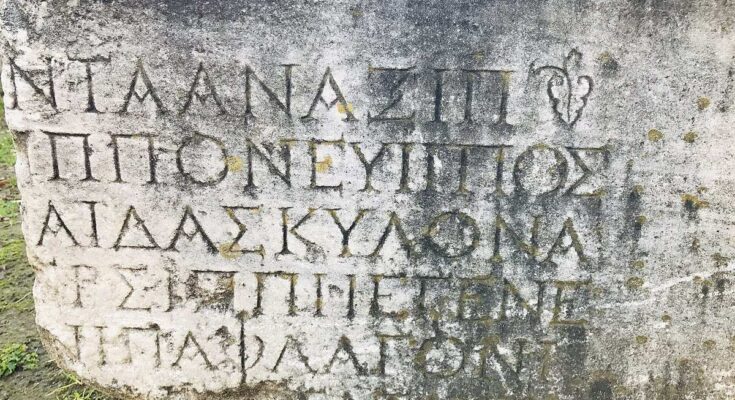

The history of the ancient Greek written language is a fascinating journey that spans several millennia. It is one of the oldest written languages and like Chinese one of the oldest languages still spoken and written today.

The earliest known writing system associated with the Greeks is known as Linear A, which emerged around 1900 BC during the Minoan civilization on the island of Crete. However, Linear A remains undeciphered, and its exact relationship to the Greek language is still uncertain.

Around 1450 BC, a new script known as Linear B appeared in the Mycenaean civilization, which was centered on the Greek mainland. This script was deciphered in the mid-20th century by Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, revealing that Linear B was an early form of written Greek. Linear B was mainly used for administrative and economic purposes, primarily on clay tablets that recorded inventories, transactions, and other administrative information. It provides valuable insights into the Mycenaean society’s economic and cultural life.

The Mycenaean civilization eventually declined around 1100 BC due to a combination of factors, including invasions and internal unrest. Following this, the Greek Dark Ages ensued, during which writing largely disappeared from the Greek world, leading to a period of limited historical records.

Around the 9th century BC, the Greek language resurfaced in a new writing system known as the Greek alphabet. The alphabet was likely adapted from the Phoenician script, but Greeks modified it to represent their distinct language, which marked the beginning of the Greek Classical period.

The Greek alphabet revolutionized written communication in Greece, making it easier to record information and disseminate knowledge. It became the basis for numerous regional variations and adaptations, such as the Etruscan alphabet in Italy and the Cyrillic alphabet in Eastern Europe.

During the Classical period (5th and 4th centuries BC), the Greek written language flourished with the works of renowned writers and philosophers like Homer, Herodotus, Sophocles, and Plato. Literary masterpieces, philosophical treatises, and historical accounts contributed to the rich legacy of ancient Greek literature and thought.

The Greek language continued to evolve through different historical periods, including the Hellenistic period and the Byzantine era, exerting a significant influence on other cultures and languages. The legacy of ancient Greek can still be felt today, as it has left an enduring impact on Western civilization in various fields such as literature, philosophy, science, and mathematics.