For nearly seven centuries, the Romans enjoyed armed contests between gladiators in the arena. During these contests, condemned men would fight for the entertainment of the crowds, sometimes to the death.

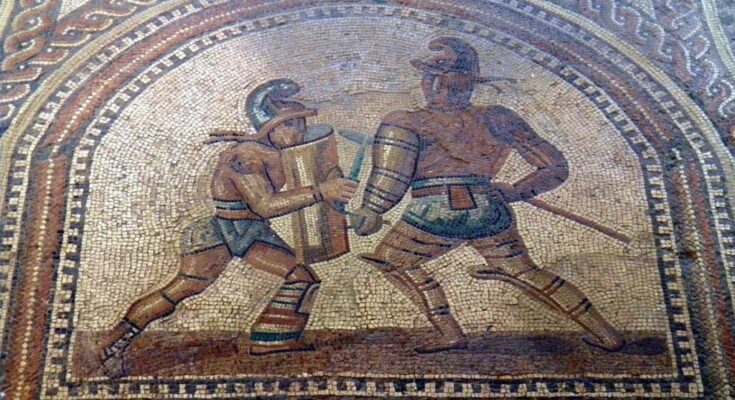

Gladiators were assigned to different armature (classes) according to their equipment and fighting style. Spectators were familiar with these classes and would have instantly recognized what types of gladiators were competing when they entered the arena. Many of these classes were inspired by the enemies of Rome and competed with the arms, armor, and martial styles of various ethnic groups and regions.

Gladiator styles inspired by the Gauls, Samnites, and Thracians were among the most ubiquitous in the arena, but there was also a class of gladiators based on the traditional ancient Greek form of fighting. The hoplomachus (plural: hoplomachii) was a Roman gladiator armed to imitate an ancient Greek hoplite.

The hoplomachii: Roman gladiators fighting in the ancient Greek style

The primary armament of the hoplomachus consisted of a spear (hasta) and a short sword or dagger wielded in the left hand, accompanied by a small round shield.

This bronze shield resembled that used by the Greek hoplite, although a typical aspides shield used by a hoplite would have been larger for use in the phalanx formation. The smaller shield offered less protection but it was easier to maneuver and could be used more offensively by the gladiator to ram it into his opponent.

For armor, the hoplomachus would don a helmet, a manica on the right arm, a subligaculum (loincloth), substantial padding on the legs, and high greaves extending to mid-thigh.

The hoplomachus was often pitted against the murmillo, who bore the sword and shield typical of the Roman legionary. In this way, certain gladiatorial contests mimicked the wars fought between Rome and her Greek enemies. However, a hoplomachus would sometimes face off against another class of gladiator, most often the Thraex.

Greeks worked with gladiators as trainers and physicians

Cultural exchange between the Greek and Roman worlds was extensive and the Romans were keen to make use of Greek expertise for the care and instruction of their gladiators.

According to works by Lucius Flavius Philostratus – an Athenian Greek philosopher and Roman citizen alive in the second and third centuries AD -, gladiators adopted a four-day training regime from Greek trainers called the tetras.

The tetras consisted of a preparation phase on the first day, an all-out training phase on the second day, relaxation on the third day, and moderate to intense exercise on the fourth day.

Greek physicians were also relied upon to treat the wounds sustained by gladiators. In fact, the most comprehensive primary source on medical care for gladiators and their diets comes from Galen, a Greek physician, surgeon, and philosopher, who lived and died between 129 and 216 AD.

In 167 AD, at the age of twenty-eight, Galen returned to his native city of Pergamon to work as a physician to the gladiators of the High Priest of Asia. According to the historian of medicine, Vivian Nutton, only two gladiators died when Galen was operating in Pergamon, whereas sixty had been killed during the tenure of his predecessor.

Galen wrote about the diet of gladiators, although he reckoned their diet of barley and a pudding made of mashed beans was suboptimal. Galen argued that this diet made the gladiators fat and flabby rather than strong and lean. The gladiators were probably fed this way because it was cheap. They were sometimes called hordearii, meaning “eaters of barley.”