The original Milindapañha or The Questions of Milinda (100 BC and 200 AD), now lost, was probably written in Sanskrit or Prakrit in Northern India. It was preserved in Ceylon and later translated into Pāli.

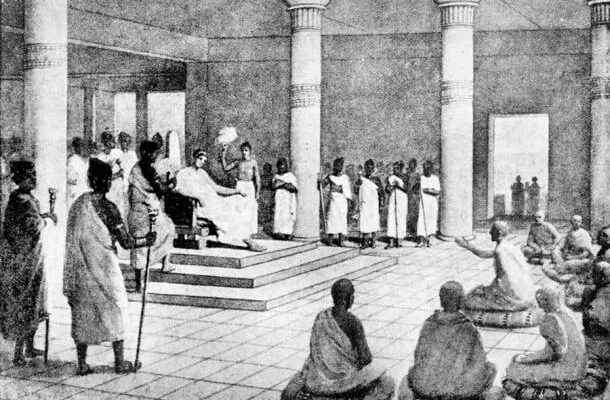

The text recounts the Socratic-like dialogue between a Yona (Greek) king, Milinda (Menander), and a Buddhist monk from Gandhāra, Nāgasena, who himself may have been of Indo-Greek origin.

According to the source, Milinda was educated in the nineteen arts and sciences. Some of these are Indian philosophies, such as “Sankhya, Yoga, Nyaya, and Vaisesika.” Similarly, the text portrays Milinda as an expert in rhetoric, a component of a Greek paideia (education).

One afternoon, after his kingly duties were completed, Milinda commanded his advisors to find him pandits (Indian sages) to answer his philosophical questions.

However, Melinda’s rhetorical skill was a match for these sages, and he petulantly clapped his hands after his opponents’ defeat, declaring:

“India is indeed an empty thing, as empty as chaff; there is no sraman or brahman (Indian philosophers) who can confer with me to dispel my doubts….”

That is until Nāgasena enters the scene. After several days of responding to the king’s ongoing inquiries about the soul, attachments, and memory, among other topics, the text describes that Milinda ceased having any doubts.

The story ends with the king removing his pride “like a cobra taking off her fangs” and handing his kingdom to his son. Later, the Indo-Greek opted to become a wanderer, eventually achieving arahantship (enlightenment).

Could an Indo-Greek king really have been a Buddhist monarch?

Who was Milinda?

According to coins, Milinda was likely Menander I or II of the Indo-Greek Kingdom (c.155–130 BC and 90 BC–10 AD). The Menanders held much of modern-day Pakistan and northern India, including the cities populated by Greeks.

The inclusion of Buddhist and Hindu imagery on coins points to the possibility that the Indo-Greek kings followed the policies of their predecessors in endorsing Indic cults, such as Buddhism.

For example, the coins of the Menanders contain multiple depictions of what has been interpreted as the dharma chakra (the wheel of dharma).

Plutarch’s mention of Menander

Even more remarkably, a Greco-Roman source seemingly verifies Menander’s conversion.

The ancient historian Plutarch independently reports that Menander was buried in a manner resembling that of a Buddhist monarch (cakkavattin), corroborating Menander’s transformation depicted in the Milindapañha.

Although Macedonian burial practices involve cremation and the placement of remains in a burial chamber, the tradition of dividing the ruler’s ashes is not observed among Macedonians.

This practice, instead, resembles the division of the remains of an individual who has reached arahantship (sainthood), intended for distribution for worship purposes.

Given that Plutarch’s account is credible as well as the strong religious inclinations of the Greeks, it is improbable that Menander, as a non-Buddhist, would have consented to be buried following a foreign tradition.

However, the conversion of Menander to Buddhism is a debated topic, mainly because we have lost the original manuscript. Rather than an outright conversion, scholars like Halkias (2014) suggest that the Menanders, as Indo-Greek rulers of various religious groups, might have portrayed themselves as Buddhist kings to better integrate with their diverse subjects, similar to rulers before them.

Alternatively, the Milindapañha might symbolize the gradual adoption of Buddhism by the Indo-Greeks. This narrative could reflect the long-term process of Greek conversion to Buddhism and the subsequent incorporation of Greek culture into Buddhism.

Ashoka rebrands Buddhism for the Greek-speaking world

Predating Menander, Ashoka the Great (c.268-232 BC) of the Mauryan Kingdom was a king close to the Greek-speaking world, both in the Mediterranean and in his domain.

During his reign, Ashoka erected numerous pillars throughout his empire, inscribing them with his Buddhist principles. These inscriptions were written in the empire’s official languages, Brāhmī and Kharosthī, as well as Greek and Aramaic, indicating Ashoka’s intent in communicating his beliefs to a diverse populace.

The Mauryan king hoped that his subjects, inspired by these messages, would embrace Buddhism as he had. One notable pillar, inscribed in Greek, was erected in Kandahar, Afghanistan, which, according to Greek sources, is possibly the ancient city of Alexandria in Arachosia.

In his 2007 work, Final Frontier, Seldeslachts contends that significant missionary activities occurred following the Third Buddhist Council during the reign of Ashoka the Great, who oversaw the council in 250 BC.

References of Greeks in Buddhist texts

An era long forgotten in Western circles but remembered in Eastern traditions highlights Buddhism’s Greek chapter. This memory is vividly recalled in the daily prayers of the Theravāda followers in Sri Lanka, preserving this historical connection.

“I bow my head to the footprints of the silent saint (Buddha) which are spread on the sandy bank of the Narmada River, on the Mountain Saccabhadda, on the Mountain Sumana, and in the city of the Yonakas (Greeks).”

Buddhist texts such as the Mahavamsa indicate that Yona Buddhists were dispatched as missionaries to their own regions of influence. Remarkably, they also occupied prestigious roles within the Buddhist religious hierarchy.

One such reference includes Yonakaloka (the country of the Greeks), which received the monk Maharakkhita, who reportedly converted “170,000 living beings.”

The text continues, “…to Aparantaka (was sent) the Yona named Dhammarakkhita,” where the Greek monk converted 37,000 living beings.

Additionally, the Mahavamsa mentions a thera (elder) Yona named Maha Dhammarakkhita. According to the text, he came from “Alasanda, the city of the Yonas,” likely referring to Alexandria in the Caucasus.

Maha Dhammarakkhita traveled with 30,000 followers to participate in the foundation ceremony of the Great Stupa at Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka.

The Indo-Greek monks’ names, like Maha Dhammarakkhita, imply that they had fully embraced their new Indian religion, as the term “dharma” frequently appears in the names of Yonaka Buddhists.

Maha Dhammarakkhita probably migrated to the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms after the fall of the Mauryan Empire.

Although the number of converts might be exaggerated, these references highlight the Yonas’ awareness of Buddhism and enthusiasm for their new religion.

The recurring use of the word “dharma” in the names of Yonaka Buddhists suggests that they had fully integrated into their new Indian religion.

The story of the Indo-Greek king who embraced Buddhism

The daily prayers of the Theravāda followers of Sri Lanka, Ashoka’s Greek Edicts, and the Milindapañha are intriguing examples of a little-known historical connection between Indian and Greek cultures.

In today’s increasingly hostile political landscape, it’s heartening to escape to a shared past that connects geographically distant parts of the world. This reminder of a common history serves as a powerful symbol of our interconnectedness.